TOBACCO

“Hail thou inspiring plant! Thou balm of life,

Well might thy worth engage two nations' strife;

Exhaustless fountain of Britannia's wealth;

Thou friend of wisdom and thou source of health.

-from an early tobacco label

Tobacco, that outlandish weed

It spends the brain, and spoiles the seede

It dulls the spirite, it dims the sight

It robs a woman of her right.”

-Dr. William Vaughn, 1617

Well might thy worth engage two nations' strife;

Exhaustless fountain of Britannia's wealth;

Thou friend of wisdom and thou source of health.

-from an early tobacco label

Tobacco, that outlandish weed

It spends the brain, and spoiles the seede

It dulls the spirite, it dims the sight

It robs a woman of her right.”

-Dr. William Vaughn, 1617

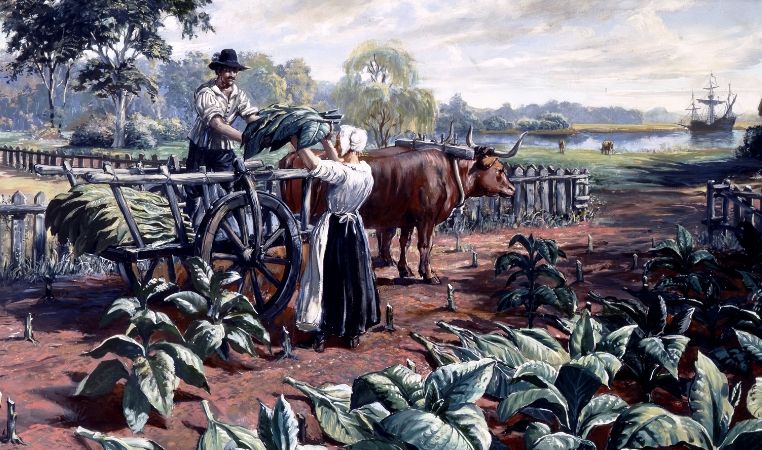

As these two verses show, tobacco use has long been a controversial subject, as a vice, a panacea, an economic salvation and a foolish and dangerous habit. Regardless of how it was perceived, by the end of the seventeenth century tobacco had become the economic staple of Virginia, easily making her the wealthiest of the 13 colonies by the time of the American Revolution.

In 1558, Frere Andre Thevet, who had traveled in Brazil, published a description of tobacco which was included in Thomas Hacket's The New Found World a decade later:

There is another secret herb . . . which they [the natives of Brazil] most commonly bear about them, for that they esteem it marvellous profitable for many things. . . . The Christians that do now inhabit there are become very desirous of this herb. . . .

Early on, the medicinal properties of tobacco were of great interest to Europe. Over a dozen books published around the middle of the sixteenth century mention tobacco as a cure for everything from pains in the joints to epilepsy to plague. As one counsel had it, "Anything that harms a man inwardly from his girdle upward might be removed by a moderate use of the herb."

In 1558, Frere Andre Thevet, who had traveled in Brazil, published a description of tobacco which was included in Thomas Hacket's The New Found World a decade later:

There is another secret herb . . . which they [the natives of Brazil] most commonly bear about them, for that they esteem it marvellous profitable for many things. . . . The Christians that do now inhabit there are become very desirous of this herb. . . .

Early on, the medicinal properties of tobacco were of great interest to Europe. Over a dozen books published around the middle of the sixteenth century mention tobacco as a cure for everything from pains in the joints to epilepsy to plague. As one counsel had it, "Anything that harms a man inwardly from his girdle upward might be removed by a moderate use of the herb."

This New World herb was used to cure the migraine headaches of Catherine de Medicis. The French became enthusiastic about tobacco, calling it the “herbe a tous les maux’, the plant against evil, pains and other bad things. By 1565, the plant was known as “nicotaine”, the basis of its genus name today. The most famous Englishman associated with the introduction of tobacco is Sir Walter Raleigh. “We ourselves during the time we were there used to suck it after their [the Native Americans'] manner, as also since our return, and have found many rare and wonderful experiments of the virtues thereof,…”

In 1604, King James I of England published his pamphlet A Counterblaste to Tobacco, in which he describes smoking as:

“A custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and the black stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless.” Part of James' disaffection for tobacco may be attributed to his personal dislike of Sir Walter Raleigh. Another factor was the Spanish monopoly over the production and distribution of the plant, which was worth its weight in silver at the end of the sixteenth century. James I solved the former problem by beheading his enemy; Raleigh was beheaded in London, for supposedly a conspiracy against King James I.

In 1604, King James I of England published his pamphlet A Counterblaste to Tobacco, in which he describes smoking as:

“A custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and the black stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless.” Part of James' disaffection for tobacco may be attributed to his personal dislike of Sir Walter Raleigh. Another factor was the Spanish monopoly over the production and distribution of the plant, which was worth its weight in silver at the end of the sixteenth century. James I solved the former problem by beheading his enemy; Raleigh was beheaded in London, for supposedly a conspiracy against King James I.

In the spring of 1610, the young John Rolfe arrived at Jamestown along with Samuel Jordan, both having survived the shipwreck of the Sea Adventure.

They we part of the The Third Supply fleet that left England in May 1609, however they ended up spending 10 months on the “Isle of the Devils” (Bermuda) where Rolfe’s wife and new born child would unfortunately die. Both men were recognized as Ancient Planters of Virginia by King James I, given land grants and would eventually be growing tobacco on adjoining plantations - some 30 miles up river, away from Jamestown.

The native tobacco from Virginia was not liked by the English settlers, nor did it appeal to the market in England.

They we part of the The Third Supply fleet that left England in May 1609, however they ended up spending 10 months on the “Isle of the Devils” (Bermuda) where Rolfe’s wife and new born child would unfortunately die. Both men were recognized as Ancient Planters of Virginia by King James I, given land grants and would eventually be growing tobacco on adjoining plantations - some 30 miles up river, away from Jamestown.

The native tobacco from Virginia was not liked by the English settlers, nor did it appeal to the market in England.

17th Century Tobacco Jar

This new settlers observed the Powhatan Indians growing tobacco. An English pamphlet of the time reported that:

“The people in the South parts of Virginia esteeme it [tobacco] exceedingly . . . ; they say that God in the creation did first make a woman, then a man, thirdly great maize, or Indian wheat, and fourthly, Tobacco.”

Rolfe, however, was not impressed with the quality, which his contemporary William Strachey characterized as "poore and weake, and of a byting tast. . .," inferior in quality to the fine Spanish weed "tabacum". Perhaps, however, the crop of the Powhatans gave Rolfe the idea of trying to grow tabacum in Virginia soil for himself.

Rolfe wanted to introduce sweeter strains from Trinidad, using the hard-to-obtain Spanish seeds he named his Virginia-grown strain of the tobacco "Orinoco", possibly in honor of tobacco popularized by Sir Walter Raleigh's expeditions in the 1580s up the Orinoco River in Guiana in search of the legendary City of Gold, El Dorado. The first harvest of four barrels of tobacco leaf was exported from Virginia to England in March 1614. Soon afterwards, Rolfe and others were exporting vast quantities of the new cash crop.

How Rolfe came by fine Trinadad tobacco seed is not known, but he was growing it experimentally by 1612 in Virginia. Rolfe's agricultural attempt was an unqualified success. By 1614, Ralph Hamor, a secretary of the Colony, reported: “Tobacco, whose goodnesse mine own experience and triall induces me to be such, that no country under the Sunne, may, or doth affoord more pleasant, sweet and strong Tobacco, then I have tasted. . . . I doubt not, [we] will make and returne such Tobacco this yeere, that even England shall acknowledge the goodnesse thereof.”

Although Sir Thomas Dale, deputy-governor of Virginia, initially limited tobacco cultivation in the fear that the settlers would neglect basic survival needs in their eagerness to finally get rich, 2,300 pounds of tobacco were exported to the Mother Country in 1615-16. Tobacco was so work-intensive that it helped fuel the need for indentured servants.

This was a paltry amount compared with the over 50,000 pounds imported from Spain in the same period, but it was a start. In 1616, Rolfe visited England with his new wife Pocohontas and presented James I with a pamphlet in which the Virginian modestly revealed tobacco as "the principall commoditie the colony for the present yieldeth."

Little did Rolfe know how important his tobacco crop would become to the economic survival of Virginia. Initially, the settlers went overboard, with predictable results. A description of Jamestown in 1617 paints a bleak picture: "but five or six houses, the church downe, the palizado's broken, the bridge in pieces, the well of fresh water spoiled; the storehouse used for the church. . . , [and] the colony dispersed about, planting tobacco."

John Rolfe Born 1585, died in 1622, he was unable to make it in time to the Jordan compound -a palisaded fort that enclosed 11 buildings, during in the Indian massacre of 1622, he was only 37.

“The people in the South parts of Virginia esteeme it [tobacco] exceedingly . . . ; they say that God in the creation did first make a woman, then a man, thirdly great maize, or Indian wheat, and fourthly, Tobacco.”

Rolfe, however, was not impressed with the quality, which his contemporary William Strachey characterized as "poore and weake, and of a byting tast. . .," inferior in quality to the fine Spanish weed "tabacum". Perhaps, however, the crop of the Powhatans gave Rolfe the idea of trying to grow tabacum in Virginia soil for himself.

Rolfe wanted to introduce sweeter strains from Trinidad, using the hard-to-obtain Spanish seeds he named his Virginia-grown strain of the tobacco "Orinoco", possibly in honor of tobacco popularized by Sir Walter Raleigh's expeditions in the 1580s up the Orinoco River in Guiana in search of the legendary City of Gold, El Dorado. The first harvest of four barrels of tobacco leaf was exported from Virginia to England in March 1614. Soon afterwards, Rolfe and others were exporting vast quantities of the new cash crop.

How Rolfe came by fine Trinadad tobacco seed is not known, but he was growing it experimentally by 1612 in Virginia. Rolfe's agricultural attempt was an unqualified success. By 1614, Ralph Hamor, a secretary of the Colony, reported: “Tobacco, whose goodnesse mine own experience and triall induces me to be such, that no country under the Sunne, may, or doth affoord more pleasant, sweet and strong Tobacco, then I have tasted. . . . I doubt not, [we] will make and returne such Tobacco this yeere, that even England shall acknowledge the goodnesse thereof.”

Although Sir Thomas Dale, deputy-governor of Virginia, initially limited tobacco cultivation in the fear that the settlers would neglect basic survival needs in their eagerness to finally get rich, 2,300 pounds of tobacco were exported to the Mother Country in 1615-16. Tobacco was so work-intensive that it helped fuel the need for indentured servants.

This was a paltry amount compared with the over 50,000 pounds imported from Spain in the same period, but it was a start. In 1616, Rolfe visited England with his new wife Pocohontas and presented James I with a pamphlet in which the Virginian modestly revealed tobacco as "the principall commoditie the colony for the present yieldeth."

Little did Rolfe know how important his tobacco crop would become to the economic survival of Virginia. Initially, the settlers went overboard, with predictable results. A description of Jamestown in 1617 paints a bleak picture: "but five or six houses, the church downe, the palizado's broken, the bridge in pieces, the well of fresh water spoiled; the storehouse used for the church. . . , [and] the colony dispersed about, planting tobacco."

John Rolfe Born 1585, died in 1622, he was unable to make it in time to the Jordan compound -a palisaded fort that enclosed 11 buildings, during in the Indian massacre of 1622, he was only 37.

Proudly powered by Weebly