Local histories are often in error because of several different reasons. First when a new settlement was established, recording the precise date of events was not always done; survival came before historic detail. Second, when the facts were finally written down, specifics were forgotton; so, stories were not always factual and were somtimes embellished by the teller's memories. Third, handwriting and abbreviations were sometimes misread; it was common to abbreviate first names or use only initials. There was no standard penmanship form and many writers had little or no formal education.

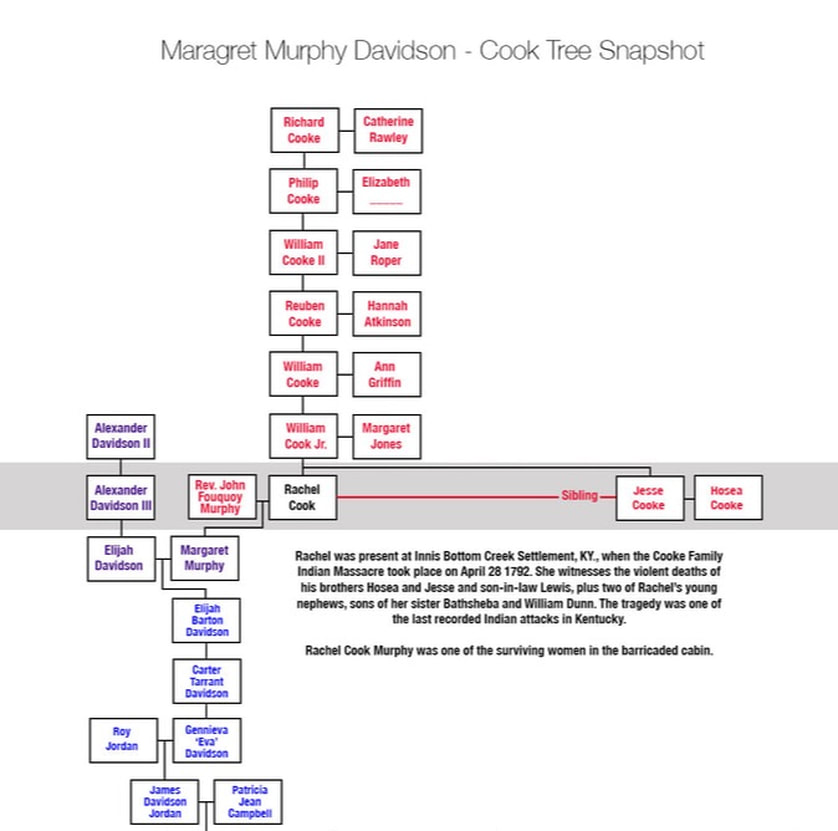

On 4 February 1802, Margaret Murphy married Elijah Davidson in Barren County, Kentucky. She was the daughter of John MURPHY and Rachel COOK. John Murphy was born 25 JUN 1750 in Halifax Co., VA. and died 13 AUG 1818 in Warren Co. KY. He married Rachel Cook on 8 FEB, 1774 in Pittsylvania Co., VA.

Rachel was the eldest of eleven children. The others were Bathsheba, Helen, Rhoda, William III, Jesse, Seth, Margaret, Hosea, Abraham and Eunice.

Rachel Cook Murphy’s 2 brothers named Hosea and Jesse Cook, her 2 sisters, Bathsheba Cook Dunn and Margaret Cook Mastin, all had moved to Frankfort KY 1791 with their families.

In the winter of 1791, their new settlement was formed on main Elkhorn about three or four miles below the juncture of the North and South forks, by the families of Jesse Cook, Hosea Cook, Lewis Mastin, William Dunn, William Bledsoe and the overseer of Col. Innis, with three negro men. There was also a single man by the name of McAndre, who resided in the settlement. Their cabins were built about three or four hundred yards apart, in the woods, interwoven with thick cane and undergrowth, so that they could not be readily seen from each other, in what was called Innis’ Bottom. Here they remained undisturbed more than a year.

On November 4, 1791 in the Northwest Territory of the United States of America (Ohio), the Battle of Wabash River or the Battle of a Thousand Slain was a fought. The U.S. Army faced the Western Confederacy of Native Americans, as part of the Northwest Indian War. It was "the most decisive defeats in the history of the American military. It was the largest victory ever won by Native Americans.

The natives were led by Little Turtle of the Miamis, Blue Jacket of the Shawnees and Buckongahelas of the Delawares (Lenape). The war party numbered more than one thousand warriors, including a large number of Potawatomis from eastern Michigan and the Saint Joseph. The opposing force of about 1,000 Americans was led by General Arthur St. Clair. The forces of the American Indian confederacy attacked at dawn, taking St. Clair's men by surprise. Of the 1,000 officers and men that St. Clair led into battle, only 24 escaped unharmed.

Six short months later; on April 28th, 1792, tragedy struck. The facts in the following account of an attack on Innis’ settlement, near Frankfort, in April, 1792, are primarily derived from the Rev. Abraham Cook, a venerable minister of the Baptist church, himself a pioneer, who died in 1855, 90 years of age, and the brother of Jesse and Hosea Cook, the husbands of the two intrepid and heroic females whose bravery is here recorded:

The survivors’ accounts were no doubt were told and retold by fascinated grandchildren and great grandchildren, the narrative was also preserved in newspaper writing decades later.

On 4 February 1802, Margaret Murphy married Elijah Davidson in Barren County, Kentucky. She was the daughter of John MURPHY and Rachel COOK. John Murphy was born 25 JUN 1750 in Halifax Co., VA. and died 13 AUG 1818 in Warren Co. KY. He married Rachel Cook on 8 FEB, 1774 in Pittsylvania Co., VA.

Rachel was the eldest of eleven children. The others were Bathsheba, Helen, Rhoda, William III, Jesse, Seth, Margaret, Hosea, Abraham and Eunice.

Rachel Cook Murphy’s 2 brothers named Hosea and Jesse Cook, her 2 sisters, Bathsheba Cook Dunn and Margaret Cook Mastin, all had moved to Frankfort KY 1791 with their families.

In the winter of 1791, their new settlement was formed on main Elkhorn about three or four miles below the juncture of the North and South forks, by the families of Jesse Cook, Hosea Cook, Lewis Mastin, William Dunn, William Bledsoe and the overseer of Col. Innis, with three negro men. There was also a single man by the name of McAndre, who resided in the settlement. Their cabins were built about three or four hundred yards apart, in the woods, interwoven with thick cane and undergrowth, so that they could not be readily seen from each other, in what was called Innis’ Bottom. Here they remained undisturbed more than a year.

On November 4, 1791 in the Northwest Territory of the United States of America (Ohio), the Battle of Wabash River or the Battle of a Thousand Slain was a fought. The U.S. Army faced the Western Confederacy of Native Americans, as part of the Northwest Indian War. It was "the most decisive defeats in the history of the American military. It was the largest victory ever won by Native Americans.

The natives were led by Little Turtle of the Miamis, Blue Jacket of the Shawnees and Buckongahelas of the Delawares (Lenape). The war party numbered more than one thousand warriors, including a large number of Potawatomis from eastern Michigan and the Saint Joseph. The opposing force of about 1,000 Americans was led by General Arthur St. Clair. The forces of the American Indian confederacy attacked at dawn, taking St. Clair's men by surprise. Of the 1,000 officers and men that St. Clair led into battle, only 24 escaped unharmed.

Six short months later; on April 28th, 1792, tragedy struck. The facts in the following account of an attack on Innis’ settlement, near Frankfort, in April, 1792, are primarily derived from the Rev. Abraham Cook, a venerable minister of the Baptist church, himself a pioneer, who died in 1855, 90 years of age, and the brother of Jesse and Hosea Cook, the husbands of the two intrepid and heroic females whose bravery is here recorded:

The survivors’ accounts were no doubt were told and retold by fascinated grandchildren and great grandchildren, the narrative was also preserved in newspaper writing decades later.

The tragedy that occurred at Cook’s Station began with an ominous precursor that no one seem to heed. That a lone Indian was seen riding through the settlement one winter night. This area was suppose to be exempt from lndian depredations stemming from a peace treaty that was designed to keep the Shawnee and Mingo Indian hunting parties north of the Ohio River.

The Cooks and their neighbors prepared to put out their crops that following spring and to clear ground of fallen timber, and split rails. On the 28th of April, 1792, the settlement came under attack, a war party of a a hundred or more, simultaneously attacked the settlement from three different advantaged points. Firing from behind fallen trees that had accumulated along the river bank, war cries are heard followed the first shots and then the war party charged out into the clearing and broke out into smaller groups, each to attack a different cabin.

At the very onset, the attack was first made upon the two Cook brothers. The sharp crack of rifles was the first inclination of the close proximity of the Indians and those first shots were fatal to the elder brother Jesse, who fell dead immediately, the younger Hosea, mortally wounded, managed to drag himself toward the Cook cabins.

The two Cook wives, who were also outside, rushed over, dragging the the body of the dying husband to the cabin. Inside were two children, as well as one slave child. They barred the puncheon door, and discovered there was only one firearm between them. Fortunately, no windows had been cut into the logs walls, essentially creating a box with only a door as a means of enter or exit. They were safely barricaded in, or so they thought. The attacking Indians, unable to enter, discharged their rifles at the door, but without injury, as the balls could not penetrate through the thick timbers of which it was constructed.

Safe inside the cabin the female occupants listen as the Indians’ attempt to cut it down the door with their tomahawks, but with no better success. While these things occurred outside the walls, there was deep sorrow, mingled with fearless determination and high resolve within. Hosea Cook, mortally wounded, after the door was barred, sunk down on the floor, and breathed his last; and the two Mrs. Cooks were left the sole defenders of the cabin.

Family accounts written years later, claim there was a third woman in the cabin, Rachel Cook, the eldest sister who come to help with the pregnancy and expected delivery of her younger sister-in-law.

Terrified by the pounding at the door, the women inside tried to load the one rifle. They had a pouch with lead balls, but they were too large. So one cut the lead and then fashioned into a smaller musket ball by using her teeth. Meanwhile, one of the women poured in the powder, jamming in the smaller piece of lead ball, they succeeded in loading the rifle. Through a small lookout hole in the cabin wall they could see one Indian seated on a stump close too the other dead brother still outside the cabin.

Working the barrel of the rifle between the logs, the elder Mrs Cook took aimed at the seating Indian who was busy yelping and shouting, and fired. The Indian sprang up high and fell over dead.

The death of the Indian infuriated the others and two of them quickly climbed onto the roof and used firebrands hoping to touched the roof. One of the women climbed up into the loft while another handed up a pail of water which they managed to douse the smoldering flame. Wasting no time the Indian tried started a second fire, and the besieged women use the last of the remaining to put it out.

Again, another fire was started and the women used a pan of milk, then they found some eggs to use to damper the next one.

The two young mothers inside, working in near silence, motioning with their hands making signals to communicate back and forth, now even more desperate pulled the bloody shirt from the dead husband’s body and thrusts into the smoldering hole.

When the first shots sounded, Louis Mastin, in conversation with McAndre took a ball into his knee. As he hobbled toward his cabin, a second shot dropped him killing him instantly. McAndre realizing they were being overrun, quickly jumped onto his horse, rode toward his cabin and was able to swoop up one of the small Mastin children by leaning with one arm and headed towards Frank’s Ford river ferry and settlement, (Frankfort) 5 miles away for help. At that time there was no actual fort at Frank’s Ford.

Indians knew immediately it wouldn’t be long before the while settlement at Frankfort would come to the settler’s aid.

William Dunn, a husband to Bathsheba Cook (sister), and his two sons, one sixteen and the other nine, made it into the woods. But in their frantic run the were separated amid the chaos. The Indians discovered the two boys hiding and murdered them, William ,the father escaped.

Margaret Jone Cook, the mother of the Cook brothers, and grandmother to the two Dunn children apparently never forgave William thereafter because he fled to safety without the boys

John Bohannon (married to Helen Cook) who was plowing at the onset of the attack was killed and his boy was never found. Years later long after the attack, bones suspected to those of the boy were found in the area.

Many of the Indians who attacked the other cabins had already started to run off, thinking they heard hoofbeats of a approaching relief party.

Back at the Cook’s cabin, realizing that time was working against them, the Indian dragged their fallen comrade from the stump down to he creek and set him afloat in the current.

One Indian who had climbed a nearby tree, fired a final, desperate shot at the upper part of the cabin, where one of women was posted in the loft. The lead ball zipped through, her her head and passed through her Bonet or hat.

The attack had taken it’s toll, two Cook brothers, Lewis Mastin, the Dunn boys, John Bohannon and his son and two slaves. The Indians mercilessly butchered one who was laying sick in bed, and carried the other off as a prisoner.

The Elkhorn Creek current carried off the dead Indian down river, later to be found wedged against some rocks. It wasn’t until after the Indians left the women found a saucerful of lead bullets under the bed. As strange as it may seem, one of the women apparently said it was too bad the Indians left before they could get a few more shots in.

Word of the attack spread quickly through the area and beyond. Daniel Trabue a Revolutionary War veteran who lived 12 miles away, arrived on the scene the next morning in the aftermath of the massacre. There he witnessed first hand the effects of the “mischief” that had been done. They saw the bloody ground where the brother fell. Blood in the cabin floor where the second collapsed and died and the blood where the Indian sitting on the stump had been slain.

He found the two widows washing their husbands bloody clothes, still shaken. After the Indians had left them, they had remained in the cabin for more than two hours, until Colonel John Finney arrived with a company of men. The two wives had been so terrified they hadn’t cried for their husband until they felt themselves safe.

A party of men was assembled to pursue the Indians, but could not “strike their trail”, because a smaller party of Indians cunningly laid low, waiting to ambush of any pursuers. When the searches turned back, the Indians slipped off north toward the Ohio River. This information was learned from 16 year old Jared Demint, who had been captured, but had managed to escape before they crossed the river into Ohio.

The Indians were Wyandotte, one of the tribes living in the Ohio territory or was known then as the Northwest Territory. They had alliances with the Shawnees, who regarded them as “younger brothers”. During the American Revolution they were used as mercenaries by the British Army to attack settlements on the western frontier.

They were know for their many incursions into the Kentucky country, including the siege of Bryans Station and the disastrous defeat of the Kentucky Militia at the Battle of Blue Licks.

The Battle of Blue Licks, fought on August 19, 1782, was one of the last battles of the American Revolutionary War. The battle occurred ten months after Lord Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown, The Battle at Blue Licks was led by the notorious Simon Girty.

One of the surviving “Betsys” later said she believed the that the notorious border renegade who led the raiding party was Simon Girty. She claimed to have heard a distinctive voice and Irish accent apart from the Indians. Girty had acquired such strong influence over Indian war parties that he accompanied and led them on raids into Pennsylvania and Kentucky settlements. On a foray in 1782 his reputation for cruelty was documented by a witness who reported Girty's participation in the torture-murder of Col. William Crawford.

The Cooks and their neighbors prepared to put out their crops that following spring and to clear ground of fallen timber, and split rails. On the 28th of April, 1792, the settlement came under attack, a war party of a a hundred or more, simultaneously attacked the settlement from three different advantaged points. Firing from behind fallen trees that had accumulated along the river bank, war cries are heard followed the first shots and then the war party charged out into the clearing and broke out into smaller groups, each to attack a different cabin.

At the very onset, the attack was first made upon the two Cook brothers. The sharp crack of rifles was the first inclination of the close proximity of the Indians and those first shots were fatal to the elder brother Jesse, who fell dead immediately, the younger Hosea, mortally wounded, managed to drag himself toward the Cook cabins.

The two Cook wives, who were also outside, rushed over, dragging the the body of the dying husband to the cabin. Inside were two children, as well as one slave child. They barred the puncheon door, and discovered there was only one firearm between them. Fortunately, no windows had been cut into the logs walls, essentially creating a box with only a door as a means of enter or exit. They were safely barricaded in, or so they thought. The attacking Indians, unable to enter, discharged their rifles at the door, but without injury, as the balls could not penetrate through the thick timbers of which it was constructed.

Safe inside the cabin the female occupants listen as the Indians’ attempt to cut it down the door with their tomahawks, but with no better success. While these things occurred outside the walls, there was deep sorrow, mingled with fearless determination and high resolve within. Hosea Cook, mortally wounded, after the door was barred, sunk down on the floor, and breathed his last; and the two Mrs. Cooks were left the sole defenders of the cabin.

Family accounts written years later, claim there was a third woman in the cabin, Rachel Cook, the eldest sister who come to help with the pregnancy and expected delivery of her younger sister-in-law.

Terrified by the pounding at the door, the women inside tried to load the one rifle. They had a pouch with lead balls, but they were too large. So one cut the lead and then fashioned into a smaller musket ball by using her teeth. Meanwhile, one of the women poured in the powder, jamming in the smaller piece of lead ball, they succeeded in loading the rifle. Through a small lookout hole in the cabin wall they could see one Indian seated on a stump close too the other dead brother still outside the cabin.

Working the barrel of the rifle between the logs, the elder Mrs Cook took aimed at the seating Indian who was busy yelping and shouting, and fired. The Indian sprang up high and fell over dead.

The death of the Indian infuriated the others and two of them quickly climbed onto the roof and used firebrands hoping to touched the roof. One of the women climbed up into the loft while another handed up a pail of water which they managed to douse the smoldering flame. Wasting no time the Indian tried started a second fire, and the besieged women use the last of the remaining to put it out.

Again, another fire was started and the women used a pan of milk, then they found some eggs to use to damper the next one.

The two young mothers inside, working in near silence, motioning with their hands making signals to communicate back and forth, now even more desperate pulled the bloody shirt from the dead husband’s body and thrusts into the smoldering hole.

When the first shots sounded, Louis Mastin, in conversation with McAndre took a ball into his knee. As he hobbled toward his cabin, a second shot dropped him killing him instantly. McAndre realizing they were being overrun, quickly jumped onto his horse, rode toward his cabin and was able to swoop up one of the small Mastin children by leaning with one arm and headed towards Frank’s Ford river ferry and settlement, (Frankfort) 5 miles away for help. At that time there was no actual fort at Frank’s Ford.

Indians knew immediately it wouldn’t be long before the while settlement at Frankfort would come to the settler’s aid.

William Dunn, a husband to Bathsheba Cook (sister), and his two sons, one sixteen and the other nine, made it into the woods. But in their frantic run the were separated amid the chaos. The Indians discovered the two boys hiding and murdered them, William ,the father escaped.

Margaret Jone Cook, the mother of the Cook brothers, and grandmother to the two Dunn children apparently never forgave William thereafter because he fled to safety without the boys

John Bohannon (married to Helen Cook) who was plowing at the onset of the attack was killed and his boy was never found. Years later long after the attack, bones suspected to those of the boy were found in the area.

Many of the Indians who attacked the other cabins had already started to run off, thinking they heard hoofbeats of a approaching relief party.

Back at the Cook’s cabin, realizing that time was working against them, the Indian dragged their fallen comrade from the stump down to he creek and set him afloat in the current.

One Indian who had climbed a nearby tree, fired a final, desperate shot at the upper part of the cabin, where one of women was posted in the loft. The lead ball zipped through, her her head and passed through her Bonet or hat.

The attack had taken it’s toll, two Cook brothers, Lewis Mastin, the Dunn boys, John Bohannon and his son and two slaves. The Indians mercilessly butchered one who was laying sick in bed, and carried the other off as a prisoner.

The Elkhorn Creek current carried off the dead Indian down river, later to be found wedged against some rocks. It wasn’t until after the Indians left the women found a saucerful of lead bullets under the bed. As strange as it may seem, one of the women apparently said it was too bad the Indians left before they could get a few more shots in.

Word of the attack spread quickly through the area and beyond. Daniel Trabue a Revolutionary War veteran who lived 12 miles away, arrived on the scene the next morning in the aftermath of the massacre. There he witnessed first hand the effects of the “mischief” that had been done. They saw the bloody ground where the brother fell. Blood in the cabin floor where the second collapsed and died and the blood where the Indian sitting on the stump had been slain.

He found the two widows washing their husbands bloody clothes, still shaken. After the Indians had left them, they had remained in the cabin for more than two hours, until Colonel John Finney arrived with a company of men. The two wives had been so terrified they hadn’t cried for their husband until they felt themselves safe.

A party of men was assembled to pursue the Indians, but could not “strike their trail”, because a smaller party of Indians cunningly laid low, waiting to ambush of any pursuers. When the searches turned back, the Indians slipped off north toward the Ohio River. This information was learned from 16 year old Jared Demint, who had been captured, but had managed to escape before they crossed the river into Ohio.

The Indians were Wyandotte, one of the tribes living in the Ohio territory or was known then as the Northwest Territory. They had alliances with the Shawnees, who regarded them as “younger brothers”. During the American Revolution they were used as mercenaries by the British Army to attack settlements on the western frontier.

They were know for their many incursions into the Kentucky country, including the siege of Bryans Station and the disastrous defeat of the Kentucky Militia at the Battle of Blue Licks.

The Battle of Blue Licks, fought on August 19, 1782, was one of the last battles of the American Revolutionary War. The battle occurred ten months after Lord Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown, The Battle at Blue Licks was led by the notorious Simon Girty.

One of the surviving “Betsys” later said she believed the that the notorious border renegade who led the raiding party was Simon Girty. She claimed to have heard a distinctive voice and Irish accent apart from the Indians. Girty had acquired such strong influence over Indian war parties that he accompanied and led them on raids into Pennsylvania and Kentucky settlements. On a foray in 1782 his reputation for cruelty was documented by a witness who reported Girty's participation in the torture-murder of Col. William Crawford.

Indian, Frontiersmen & Simon Girty Reenactors

Cabins at Cook's Station

Cook Family Ancestry

WILLIAM COOK JR - Born c1730, Brunswick Co., VA. D. 22 May, 1790, Woodford County, Kentucky

Married Margaret Jones in 1750 Lunenburg Co., Virginia

Born circa 1734 - She died in 1797 Franklin County, Kentucky

Their children (order of birth estimated):

1. Rachel Cook

b. 17 May 1753 Virginia

d. 03 Feb 1832 Warren County, Kentucky

m. John Murphy 08 Feb 1774 Pittsylvania County, Virginia, Rachel, while visiting her siblings, survived the attack at Cook’s Station.

2. Bathsheba Cook

b. c1755 Virginia

m. William Dunn in 1776, He died at the Cook Massacre, 28 Apr 1792 Woodford County, Kentucky as did their two sons. Bathsheba Cook survived the attack.

3. Helen Cook

b. 1756 Virginia

d. 1837 Shelby County, Kentucky

m. 68. John Bohannon 07 Jan 1774 Pittsylvania County, VA, He died at the Cook Massacre 28 Apr 1792 Woodford County, Kentucky as did one of their sons, Helen survived the attack.

4. Rhoda Cook

b. c1760 Virginia

m. (1) Joshua Bohannon

(2) John Jameson 16 Oct 1781 Lincoln County, Virginia

5. William Cook III

b. c1764 Virginia

d. 16 Mar 1816 Shelby County, Kentucky

m. Katherine (Keturah) Crutcher 24 Feb 1798 Franklin County, Kentucky

6. Jesse Cook

b. c1765 Virginia

He died at the Cook Massacre, 28 Apr 1792 Woodford County, Kentucky

m. Elizabeth “Betsy” Bohannon 1 Sep 1785 in Henry County. Betsy survived the attack.

7. Seth Cook

b. between 1760-1770 Virginia

d. 1840 Shelby County, Kentucky

m. (1) Frances Wilcoxson 27 Feb 1796 Woodford County, Kentucky

(2) Lydia “Ann” Guthrie

8. Margaret Cook

b. c1767 Virginia

m. (1) Lewis Mastin, he died at the Cook Massacred. 28 Apr 1792 Woodford County, Kentucky

(2) James Hackett 18 Jan 1797 Franklin County, Kentucky

Margaret survived the attack

9. Hosea Cook

b. c1769

He died at the Cook Massacre, 28 Apr 1792 Woodford County, Kentucky

m. Elizabeth “Betsy” Edrington 3 Dec 1791 in Woodford County, Kentucky

Betsy survived the attack.

10. Abraham Cook

b. 06 Jul 1774 Franklin County, Virginia

d. 10 Feb 1854 McFall, Missouri

m. Sarah Jones 07 Sep 1795 Franklin County, Kentucky

11. Eunice Cook

b. c1775 Virginia

d. c1800

m. Samuel Miles 27 Feb 1797 Franklin County, Kentucky

William Cook, Jr. was identified as the only son of William Cook and Ann Griffin (Griffith) in the family Bible of William Cook III.

The Cook Bible identifies his wife as Margaret Jones. An analysis of all pertinent records in Franklin County, Virginia, and the surrounding area, provides circumstantial evidence, without any contradictory data, that indicates that Margaret Jones was a daughter of Robert Jones and Mary Van Meter who moved from Frederick County, Virginia, to the part of Lunenburg County that eventually became, Halifax, Pittsylvania, Henry and Franklin counties, Virginia.

William Cook is listed in the vestry book of Cumberland Parish in 1751, as a reader at the houses of Joseph Rentfro and Mark Cole on the Blackwater River: A reader was a layman of the Church of England who conducted religious services during the scarcity of ordained ministers. Readers were paid by a county tobacco levy.

That May, President Washington urged Congress to raise an army capable of conducting a successful offense against the American Indian confederacy, it also passed two Militia Acts: the first empowered the president to call out the militias of the several states; the second required that every free able-bodied white male citizen of the various states, between the ages of 18 and 45, enroll in the militia of the state in which they reside.

WILLIAM COOK JR - Born c1730, Brunswick Co., VA. D. 22 May, 1790, Woodford County, Kentucky

Married Margaret Jones in 1750 Lunenburg Co., Virginia

Born circa 1734 - She died in 1797 Franklin County, Kentucky

Their children (order of birth estimated):

1. Rachel Cook

b. 17 May 1753 Virginia

d. 03 Feb 1832 Warren County, Kentucky

m. John Murphy 08 Feb 1774 Pittsylvania County, Virginia, Rachel, while visiting her siblings, survived the attack at Cook’s Station.

2. Bathsheba Cook

b. c1755 Virginia

m. William Dunn in 1776, He died at the Cook Massacre, 28 Apr 1792 Woodford County, Kentucky as did their two sons. Bathsheba Cook survived the attack.

3. Helen Cook

b. 1756 Virginia

d. 1837 Shelby County, Kentucky

m. 68. John Bohannon 07 Jan 1774 Pittsylvania County, VA, He died at the Cook Massacre 28 Apr 1792 Woodford County, Kentucky as did one of their sons, Helen survived the attack.

4. Rhoda Cook

b. c1760 Virginia

m. (1) Joshua Bohannon

(2) John Jameson 16 Oct 1781 Lincoln County, Virginia

5. William Cook III

b. c1764 Virginia

d. 16 Mar 1816 Shelby County, Kentucky

m. Katherine (Keturah) Crutcher 24 Feb 1798 Franklin County, Kentucky

6. Jesse Cook

b. c1765 Virginia

He died at the Cook Massacre, 28 Apr 1792 Woodford County, Kentucky

m. Elizabeth “Betsy” Bohannon 1 Sep 1785 in Henry County. Betsy survived the attack.

7. Seth Cook

b. between 1760-1770 Virginia

d. 1840 Shelby County, Kentucky

m. (1) Frances Wilcoxson 27 Feb 1796 Woodford County, Kentucky

(2) Lydia “Ann” Guthrie

8. Margaret Cook

b. c1767 Virginia

m. (1) Lewis Mastin, he died at the Cook Massacred. 28 Apr 1792 Woodford County, Kentucky

(2) James Hackett 18 Jan 1797 Franklin County, Kentucky

Margaret survived the attack

9. Hosea Cook

b. c1769

He died at the Cook Massacre, 28 Apr 1792 Woodford County, Kentucky

m. Elizabeth “Betsy” Edrington 3 Dec 1791 in Woodford County, Kentucky

Betsy survived the attack.

10. Abraham Cook

b. 06 Jul 1774 Franklin County, Virginia

d. 10 Feb 1854 McFall, Missouri

m. Sarah Jones 07 Sep 1795 Franklin County, Kentucky

11. Eunice Cook

b. c1775 Virginia

d. c1800

m. Samuel Miles 27 Feb 1797 Franklin County, Kentucky

William Cook, Jr. was identified as the only son of William Cook and Ann Griffin (Griffith) in the family Bible of William Cook III.

The Cook Bible identifies his wife as Margaret Jones. An analysis of all pertinent records in Franklin County, Virginia, and the surrounding area, provides circumstantial evidence, without any contradictory data, that indicates that Margaret Jones was a daughter of Robert Jones and Mary Van Meter who moved from Frederick County, Virginia, to the part of Lunenburg County that eventually became, Halifax, Pittsylvania, Henry and Franklin counties, Virginia.

William Cook is listed in the vestry book of Cumberland Parish in 1751, as a reader at the houses of Joseph Rentfro and Mark Cole on the Blackwater River: A reader was a layman of the Church of England who conducted religious services during the scarcity of ordained ministers. Readers were paid by a county tobacco levy.

That May, President Washington urged Congress to raise an army capable of conducting a successful offense against the American Indian confederacy, it also passed two Militia Acts: the first empowered the president to call out the militias of the several states; the second required that every free able-bodied white male citizen of the various states, between the ages of 18 and 45, enroll in the militia of the state in which they reside.

Proudly powered by Weebly