Proximity to Paradise

May 21, 1610 - Having been stranded in the Bermuda islands for nearly a year, the future Virginia colonists headed by Sir Thomas Gates arrives at Point Comfort in the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

May 24, 1610 - Aboard the Patience and Deliverance, (reconstructed ships built from the salvaged remains of the scuttled Sea Adventure on the isle of Bermuda, they finally arrive at their original destination, Jamestown. They find only sixty survivors of a winter famine, later called the "Starving Time". Surmising the futility of continuance, in swampy marshlands, brackish waters and over-whelming hostile natives, Gates believes in the prudence of survival first and foremost over company profits and decides to abandon the colony for Newfoundland.

June 8, 1610 - Sailing back down the James River toward the Chesapeake Bay and onto Newfoundland, Jamestown colonists encounter a ship bearing the new governor, Thomas West, baron De La Warr, and a year's worth of supplies. The colonists return to Jamestown that evening.

June 10, 1610 - The Virginia colony's new governor, Sir Thomas West, twelfth baron De La Warr, arrives at Jamestown and hears a sermon delivered by Reverend Richard Bucke.

July 9, 1610 - After the colonist Humphrey Blunt is taken by Indians and tortured to death near Point Comfort Sir Thomas Gates attacks a nearby Kecoughtan town, killing twelve to fourteen and confiscating the cornfields.

August 10, 1610 - At night, George Percy attacks a Paspahegh town, killing fifteen to sixteen, burning houses, and taking corn. The wife and two children of the Weroance, Wowinchopunck, are captured and executed.

May 24, 1610 - Aboard the Patience and Deliverance, (reconstructed ships built from the salvaged remains of the scuttled Sea Adventure on the isle of Bermuda, they finally arrive at their original destination, Jamestown. They find only sixty survivors of a winter famine, later called the "Starving Time". Surmising the futility of continuance, in swampy marshlands, brackish waters and over-whelming hostile natives, Gates believes in the prudence of survival first and foremost over company profits and decides to abandon the colony for Newfoundland.

June 8, 1610 - Sailing back down the James River toward the Chesapeake Bay and onto Newfoundland, Jamestown colonists encounter a ship bearing the new governor, Thomas West, baron De La Warr, and a year's worth of supplies. The colonists return to Jamestown that evening.

June 10, 1610 - The Virginia colony's new governor, Sir Thomas West, twelfth baron De La Warr, arrives at Jamestown and hears a sermon delivered by Reverend Richard Bucke.

July 9, 1610 - After the colonist Humphrey Blunt is taken by Indians and tortured to death near Point Comfort Sir Thomas Gates attacks a nearby Kecoughtan town, killing twelve to fourteen and confiscating the cornfields.

August 10, 1610 - At night, George Percy attacks a Paspahegh town, killing fifteen to sixteen, burning houses, and taking corn. The wife and two children of the Weroance, Wowinchopunck, are captured and executed.

Sir Thomas Gates

As the First Anglo-Powhatan War escalated, few restraints were in evidence, and descriptions by the colonists of the Powhatans' calling on their god Okee suggest that both sides may have seen themselves in a holy war.

By November of 1610, De La Warr sends Samuel Jordan with a large expedition of perhaps two hundred men, including miners, west toward the falls of the James. After an initial defeat at the hands of the Appamattucks' Weroansqua, or female chief, Opossunoquonuske, the colonists destroyed the Appamattuck village and severely injured the Weroansqua.

March 28, 1611 - Governor Thomas West, baron De La Warr, ill with malaria or scurvy, leaves Virginia on a ship piloted by Samuel Argall and bound for Nevis in the West Indies.

May 19, 1611 - Sir Thomas Dale arrives at Jamestown. The colony's marshal, he assumes the title of acting governor in the absence of Lieutenant Governor Sir Thomas Gates and Governor Sir Thomas West, twelfth baron De La Warr.

June 1611 - Sir Thomas Dale leads a hundred armored soldiers against the Nansemond Indians at the mouth of the James River, burning their towns.

June 22, 1611 - Sir Thomas Dale issues military regulations under which his soldiers are to act while in Virginia, supplementing civil orders released in 1610. The combined orders are printed in London the next year with the title For the Colony in Virginea Britannia. Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall, &c.

September 1611 - Sir Thomas Dale marches against Indians farther up the James River from Jamestown and establishes a settlement on a bluff that he calls the City of Henrico, or Henricus, in honor of his patron Prince Henry.

April 1613 - Samuel Argall uses his extensive knowledge of the Potomac River–northern Chesapeake area and its Indian population to kidnap Pocahontas while she is with the Patawomeck—an event that ultimately helps to bring the devastating First Anglo-Powhatan War to a conclusion in 1614.

March 1614 - Sir Thomas Dale, Captain Samuel Argall, and 150 English soldiers—with Pocahontas in tow—paddle deep into Pamunkey territory. At present-day West Point, the Englishmen face down several hundred Indians. When, after two days, neither side is willing to fire first, the colonists return to Jamestown.

March 1614 - While negotiating with Powhatan over ransom for his daughter Pocahontas, the colonist Ralph Hamor records his impression that Opechancanough has quietly achieved "command of all the people" of Tsenacomoco. He, and not the ill Powhatan, finds a resolution to the stalemate.

By November of 1610, De La Warr sends Samuel Jordan with a large expedition of perhaps two hundred men, including miners, west toward the falls of the James. After an initial defeat at the hands of the Appamattucks' Weroansqua, or female chief, Opossunoquonuske, the colonists destroyed the Appamattuck village and severely injured the Weroansqua.

March 28, 1611 - Governor Thomas West, baron De La Warr, ill with malaria or scurvy, leaves Virginia on a ship piloted by Samuel Argall and bound for Nevis in the West Indies.

May 19, 1611 - Sir Thomas Dale arrives at Jamestown. The colony's marshal, he assumes the title of acting governor in the absence of Lieutenant Governor Sir Thomas Gates and Governor Sir Thomas West, twelfth baron De La Warr.

June 1611 - Sir Thomas Dale leads a hundred armored soldiers against the Nansemond Indians at the mouth of the James River, burning their towns.

June 22, 1611 - Sir Thomas Dale issues military regulations under which his soldiers are to act while in Virginia, supplementing civil orders released in 1610. The combined orders are printed in London the next year with the title For the Colony in Virginea Britannia. Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall, &c.

September 1611 - Sir Thomas Dale marches against Indians farther up the James River from Jamestown and establishes a settlement on a bluff that he calls the City of Henrico, or Henricus, in honor of his patron Prince Henry.

April 1613 - Samuel Argall uses his extensive knowledge of the Potomac River–northern Chesapeake area and its Indian population to kidnap Pocahontas while she is with the Patawomeck—an event that ultimately helps to bring the devastating First Anglo-Powhatan War to a conclusion in 1614.

March 1614 - Sir Thomas Dale, Captain Samuel Argall, and 150 English soldiers—with Pocahontas in tow—paddle deep into Pamunkey territory. At present-day West Point, the Englishmen face down several hundred Indians. When, after two days, neither side is willing to fire first, the colonists return to Jamestown.

March 1614 - While negotiating with Powhatan over ransom for his daughter Pocahontas, the colonist Ralph Hamor records his impression that Opechancanough has quietly achieved "command of all the people" of Tsenacomoco. He, and not the ill Powhatan, finds a resolution to the stalemate.

Painting of the Baptism of Pocahontas - Displayed the US Capital Rotunda

April 5, 1614 - On or about this day, Pocahontas and John Rolfe marry in a ceremony assented to by Sir Thomas Dale and Powhatan, who sends one of her uncles to witness the ceremony. Powhatan also rescinds a standing order to attack the English wherever and whenever possible, ending the First Anglo-Powhatan War.

When the Powhatan Chief agreed to peace after the English captured his daughter Pocahontas, the former enemies had enjoyed a cordial relationship. However, as more settlers moved in, carving the land up into tobacco plantations and ruining Indian hunting grounds by driving away the game, the Powhatans saw their centuries-old way of life being destroyed.

Beginning in 1618, a faction within the London Virginia Company led by the treasurer Sir Edwin Sandys had steered the company in the direction of the integration of Indians into English settlements. Participating families received houses in the settlements and funds were established for a school for Indian youth for Christian conversions and hopefully, civilize them.

When the Powhatan Chief agreed to peace after the English captured his daughter Pocahontas, the former enemies had enjoyed a cordial relationship. However, as more settlers moved in, carving the land up into tobacco plantations and ruining Indian hunting grounds by driving away the game, the Powhatans saw their centuries-old way of life being destroyed.

Beginning in 1618, a faction within the London Virginia Company led by the treasurer Sir Edwin Sandys had steered the company in the direction of the integration of Indians into English settlements. Participating families received houses in the settlements and funds were established for a school for Indian youth for Christian conversions and hopefully, civilize them.

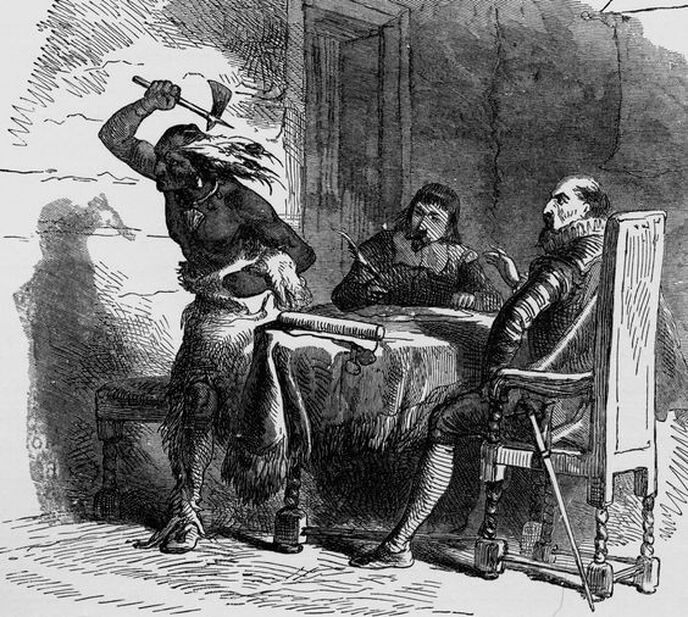

Indian Massacre of 1622

March 22, 1622 - Indians under Opechancanough unleash a series of attacks that start the Second Anglo-Powhatan War. The assault was originally planned for the fall of 1621, to coincide with the redisposition of Powhatan's bones, suggesting that the attack was to be part of the final mortuary celebration for the former chief.

Samuel Jordan had three sons by his first marriage. The sons would later followed him to America. Samuel married a local young widow, named Cecily Reynolds Bailey. Cecily arrived in the American colonies on the Swan, August 1610 (or 1611). She was ten years and alone when she arrived.

When Samuel Jordan obtained his patent, he had just married his second wife Cecily Bailey, who was herself a widow with a young daughter Temperance Bailey, about 3 years old. Cecily was the only child of Capt. Thomas Reynolds and Jane Phippen Pierce. Cecily was born in England about 1600, and was therefore about a year younger than Samuel Jordan's eldest son. Samuel Jordan 42, married Cecily 20, shortly before 10 December 1620. The Jordan's set about developing their plantation which eventually consisted of a palisade fort that enclosed 11 buildings including his home. The couple were soon expanding their family with the arrival of daughter Mary Jordan, born in 1621 or early 1622.

Opechancanough, brother of Powhatan, was " King of Pamunkey " when the English first landed in Virginia. He was born about 1552, and died in 1644. He first became known to the English as the captor of John Smith in the forest. Opechancanough would have killed him immediately, but for Smith's presence of mind. He drew from his pocket a compass, and explained to the native as well as he could its wonderful nature; told him of the form of the earth and the stars - how the sun chased the night around the earth continually. Opechancanough regarded him as a superior being, and women and children stared at him as he passed from village to village to the Indian's capital, until he was placed in the custody of Powhatan. Opechancanough attended the marriage of his niece, Pocahontas, at Jamestown. After the death of his brother (1619) he was lord of the empire, and immediately formulated plans for driving the English out of his country.

Encouraged by the relations initiated by wedding of Pocahontas and John Rolfe, they assumed that Openchancanough (Pocahontas’ uncle) and the Powhatan nation shared the same ideals of an integrated society. The Indians silence in the face of daily insults of occupation and verbal abuse, the English mistook for subservience. Not only had the Indians not agreed to cultural suicide, but as George Thorpe, a supporter of the new policy of integration, observed, most of the English settlers still harbored their contempt for Indians.

Under Gov. Sir Francis Wyatt there was evidence of great prosperity and peace every-where. But just at that time unknown to the colonists, a fearful cloud of trouble was brooding. Opechancanough commanded more than 1,500 warriors. He hated the English bitterly, and he inspired the Indian confederation with the same feeling, all-the-while, he feigned friendship for them until a plot for their destruction was perfected.

It was apparent to the Indians that the colonists’ expansion was threatening the Indian way of life. Opechancanough would spend the next few years looking for just the right opportunity to drive them off their land. That attack would come in 1622, despite maintaining the outward appearance of overall friendly relations with the English.

.

He was ultimately correct in believing the English intended to seize his domain. In an affray with a settler, an Indian leader was shot, and the wily emperor made it the occasion for inflaming the resentment of his people against the English. He visited the governor in war costume, bearing in his belt a glittering hatchet, and demanded some concessions for his incensed people. It was refused, and, forgetting himself for a moment, he snatched the hatchet from his belt and struck its keen blade into a log of the cabin, uttering a curse upon the English. Instantly recovering himself, he ,smiled, and said: " Pardon me, governor; I was thinking of that wicked Englishman (see ARGALL, SAMUEL) who stole my niece and struck me with his sword. I love the English who are the friends of Powhatan. Sooner will the skies fall than that my bond of friendship with the English shall be dissolved."

March 22, 1622 - Indians under Opechancanough unleash a series of attacks that start the Second Anglo-Powhatan War. The assault was originally planned for the fall of 1621, to coincide with the redisposition of Powhatan's bones, suggesting that the attack was to be part of the final mortuary celebration for the former chief.

Samuel Jordan had three sons by his first marriage. The sons would later followed him to America. Samuel married a local young widow, named Cecily Reynolds Bailey. Cecily arrived in the American colonies on the Swan, August 1610 (or 1611). She was ten years and alone when she arrived.

When Samuel Jordan obtained his patent, he had just married his second wife Cecily Bailey, who was herself a widow with a young daughter Temperance Bailey, about 3 years old. Cecily was the only child of Capt. Thomas Reynolds and Jane Phippen Pierce. Cecily was born in England about 1600, and was therefore about a year younger than Samuel Jordan's eldest son. Samuel Jordan 42, married Cecily 20, shortly before 10 December 1620. The Jordan's set about developing their plantation which eventually consisted of a palisade fort that enclosed 11 buildings including his home. The couple were soon expanding their family with the arrival of daughter Mary Jordan, born in 1621 or early 1622.

Opechancanough, brother of Powhatan, was " King of Pamunkey " when the English first landed in Virginia. He was born about 1552, and died in 1644. He first became known to the English as the captor of John Smith in the forest. Opechancanough would have killed him immediately, but for Smith's presence of mind. He drew from his pocket a compass, and explained to the native as well as he could its wonderful nature; told him of the form of the earth and the stars - how the sun chased the night around the earth continually. Opechancanough regarded him as a superior being, and women and children stared at him as he passed from village to village to the Indian's capital, until he was placed in the custody of Powhatan. Opechancanough attended the marriage of his niece, Pocahontas, at Jamestown. After the death of his brother (1619) he was lord of the empire, and immediately formulated plans for driving the English out of his country.

Encouraged by the relations initiated by wedding of Pocahontas and John Rolfe, they assumed that Openchancanough (Pocahontas’ uncle) and the Powhatan nation shared the same ideals of an integrated society. The Indians silence in the face of daily insults of occupation and verbal abuse, the English mistook for subservience. Not only had the Indians not agreed to cultural suicide, but as George Thorpe, a supporter of the new policy of integration, observed, most of the English settlers still harbored their contempt for Indians.

Under Gov. Sir Francis Wyatt there was evidence of great prosperity and peace every-where. But just at that time unknown to the colonists, a fearful cloud of trouble was brooding. Opechancanough commanded more than 1,500 warriors. He hated the English bitterly, and he inspired the Indian confederation with the same feeling, all-the-while, he feigned friendship for them until a plot for their destruction was perfected.

It was apparent to the Indians that the colonists’ expansion was threatening the Indian way of life. Opechancanough would spend the next few years looking for just the right opportunity to drive them off their land. That attack would come in 1622, despite maintaining the outward appearance of overall friendly relations with the English.

.

He was ultimately correct in believing the English intended to seize his domain. In an affray with a settler, an Indian leader was shot, and the wily emperor made it the occasion for inflaming the resentment of his people against the English. He visited the governor in war costume, bearing in his belt a glittering hatchet, and demanded some concessions for his incensed people. It was refused, and, forgetting himself for a moment, he snatched the hatchet from his belt and struck its keen blade into a log of the cabin, uttering a curse upon the English. Instantly recovering himself, he ,smiled, and said: " Pardon me, governor; I was thinking of that wicked Englishman (see ARGALL, SAMUEL) who stole my niece and struck me with his sword. I love the English who are the friends of Powhatan. Sooner will the skies fall than that my bond of friendship with the English shall be dissolved."

Sir Francis warned the people that treachery was abroad. They did not believe it. They so trusted the Indians that they had taught them to hunt with fire-arms. On the day prior to the attack, the Indians came bringing gifts of meats and fruits and shared them with the settlers, thereby disguising their true intentions.

The English had grown more content with the increase of new arrivals from home and the long quiet they had enjoyed among the Indians since the marriage of Pocahontas. The men were lulled into a fatal security and became ever familiar with the Indians - eating, drinking, and sleeping amongst them, by which means the Indians became perfectly acquainted with all of the English strength and the use of our arms, knowing at all times when and where the settlers’ habits, whether at home or in the woods, in groups or dispersed, and their conditions of defense or indefensible.

Then on the morning of April 1st, 1622, the Indians who had visited the colonists and stayed overnight joined others who just arrived, entered the scattered James River settlements, some using boats to cross rivers, to launch their well-coordinated surprise attacks. The Indians entered the settlements unarmed and when the time came to attack they used the colonists’ own tools and weapons to kill the English.

According to English accounts, Opechancanough had planned to overrun the Jamestown fort as well as all the outlying settlements, killing everyone in their path. But a young Indian boy who had been “Christianized” by the settlers forewarned the inhabitants that same morning. But, the news did not spread fast enough to save those living in the all the outlying settlements.

Colonist Edward Waterhouse recounted that the Powhatan were “so sudden in their cruel execution that few or none discerned the weapon or blow that brought them to their destruction. The very morning of the massacre they came freely, eating with them and behaving themselves with the same freedom and friendship as formerly till the very minute they were to put their plot in execution. Then they fell to their work all at once everywhere, knocking the English unawares on the head, some with their hatchets, which they call tomahawks, others with the hoes and axes of the English themselves, shooting at those who escaped the reach of their hands, sparing neither age nor sex but destroying man, woman, and child according to their cruel way of leaving none behind to bear resentment.”

The Indians killed families in the plantation houses and them moved on to kill servants and workers in the fields. The Powhatans killed 347 settlers in all - men, women, and children. Not even George Thorpe, well known for his friendly stance towards the Indians, was spared. The Powhatans harsh treatment of the bodies of their victims was symbolic of their contempt for their opponents. The Indians also burned most of the outlying plantations, destroying the livestock and crops.

The English had grown more content with the increase of new arrivals from home and the long quiet they had enjoyed among the Indians since the marriage of Pocahontas. The men were lulled into a fatal security and became ever familiar with the Indians - eating, drinking, and sleeping amongst them, by which means the Indians became perfectly acquainted with all of the English strength and the use of our arms, knowing at all times when and where the settlers’ habits, whether at home or in the woods, in groups or dispersed, and their conditions of defense or indefensible.

Then on the morning of April 1st, 1622, the Indians who had visited the colonists and stayed overnight joined others who just arrived, entered the scattered James River settlements, some using boats to cross rivers, to launch their well-coordinated surprise attacks. The Indians entered the settlements unarmed and when the time came to attack they used the colonists’ own tools and weapons to kill the English.

According to English accounts, Opechancanough had planned to overrun the Jamestown fort as well as all the outlying settlements, killing everyone in their path. But a young Indian boy who had been “Christianized” by the settlers forewarned the inhabitants that same morning. But, the news did not spread fast enough to save those living in the all the outlying settlements.

Colonist Edward Waterhouse recounted that the Powhatan were “so sudden in their cruel execution that few or none discerned the weapon or blow that brought them to their destruction. The very morning of the massacre they came freely, eating with them and behaving themselves with the same freedom and friendship as formerly till the very minute they were to put their plot in execution. Then they fell to their work all at once everywhere, knocking the English unawares on the head, some with their hatchets, which they call tomahawks, others with the hoes and axes of the English themselves, shooting at those who escaped the reach of their hands, sparing neither age nor sex but destroying man, woman, and child according to their cruel way of leaving none behind to bear resentment.”

The Indians killed families in the plantation houses and them moved on to kill servants and workers in the fields. The Powhatans killed 347 settlers in all - men, women, and children. Not even George Thorpe, well known for his friendly stance towards the Indians, was spared. The Powhatans harsh treatment of the bodies of their victims was symbolic of their contempt for their opponents. The Indians also burned most of the outlying plantations, destroying the livestock and crops.

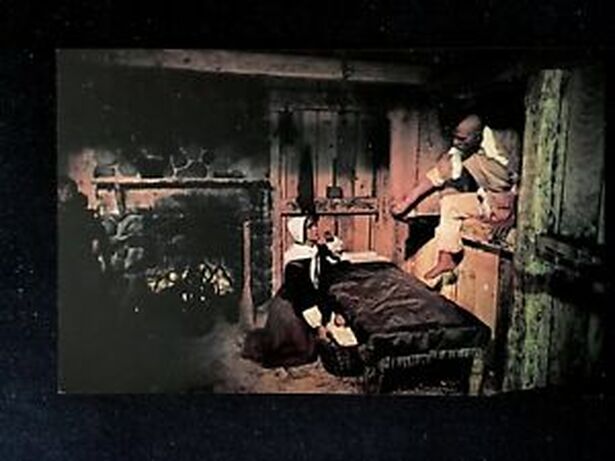

Earlier that same morning Richard Pace had rowed with “his might and main” three miles across the James river from Paces Paines to Beggar's Bush to warn Samuel Jordan of the impending blow. Without losing an instant, Samuel Jordan summoned his neighbors from far and near and gathered them all, men, women and children, within his fortified home at Beggar's Bush. Beggar’s Bush had a 10 ft. stockade fence encircling 11 buildings. Hearing of the coming attack Samuel sent his son Robert by boat across the river to warn those at the plantation of Berkley’s Hundred in Charles City. When the Indians attacked Samuel and his armed men were ready to defend – and to a great surprise to the Indians, who gave up their futile efforts and beat a hasty retreat. So resolutely was the place defended, that not a single life was lost there on that bloody day. The agony and terror of the women and children huddled together in the farthest corner of the little stronghold can only be imagined. Unfortunately, Robert who had arrived only minutes before the Indians attacked, was killed at the Berkley plantation, every one was killed at Berkley Hundred.

The next day Mr. William Farrar reached Beggar's Bush from just a few miles journey from his homestead on the Appomattox River. Ten victims had been slaughtered at his home and he himself had barely escaped to safety at the Jordan's where circumstances would force him to remain for some time.

In the aftermath, the surviving colonists in Jamestown were in an uproar, stunned by the massacre. The settlers immediately withdrew to the fort and to other easily defensible locations. In addition to the loss of life, the colonists also lost valuable crops and supplies necessary to survive the winter.

The warriors struck down the colonists with their own hammers and hatchets, they burned houses, killed livestock, scattered possessions, and mutilated the dead and dying before fleeing. The settlement of Wolstenholme Towne was ‘ruinated and spoyled’ by the Indian assault and suffered the highest death toll of any settlement during the uprising.

Although the official number of Virginia colonists killed was recorded at 347, some settlements, such as Bermuda Hundred, did not send in a report, so the number of dead was probably higher. Among the forgotten victims of the attack were the missing women of Martin’s Hundred plantation. Twenty female colonists, were the only captives taken by the Powhatans in the uprising. Few details of their ordeal have survived, and information about their lives is almost nonexistent. It is certain, however, that these women witnessed the violent deaths of neighbors and loved ones before being abducted. The dazed and despairing survivors had every reason to believe that those missing had either been killed in inaccessible areas, hacked or burned beyond recognition, or captured, which they believed would lead to certain death. In the weeks and months following the Powhatan onslaught, neither the Virginia Company officials nor the survivors of Martin’s Hundred attempted to locate and recover the missing settlers, staying alive took precedence over a hunt for neighbors they thought were beyond rescue. A year after the uprising, Richard Frethorne, a settler in Wolstenholme Towne, reported that the Powhatans held 15 people from that plantation in their villages, while another source indicated that there were ’19 English persons retayned “ . . in great slavery’ among the Indians and that ‘there were none but women in Captivitie . . . for the men they tooke they putt . . . to death.”

The Indian raids suddenly and shockingly transformed Virginia into a ‘labyrinth of melancholy,’ a severely wounded colony struggling to survive. The loss was so great that Martin’s Hundred and many other settlements were temporarily abandoned.

An English expedition along the Potomac River had received a message in late June or early July 1622 from Mistress Boyse, ‘a prisoner with nineteene more’ of the Powhatans. Mistress Boyse, who pleaded for the governor to try to secure the captives’ release, was the wife of either John Boyse, who had represented Martin’s Hundred in the first Virginia legislature of 1619, Thomas Boyse of the same plantation, who was listed among those killed in the March 1622 attack. With her at the Indian stronghold were Mistress Jeffries, wife of Nathaniel Jeffries who survived the uprising, and Jane Dickenson, wife of Ralph Dickenson, an indentured servant slain in the assault.

The next day Mr. William Farrar reached Beggar's Bush from just a few miles journey from his homestead on the Appomattox River. Ten victims had been slaughtered at his home and he himself had barely escaped to safety at the Jordan's where circumstances would force him to remain for some time.

In the aftermath, the surviving colonists in Jamestown were in an uproar, stunned by the massacre. The settlers immediately withdrew to the fort and to other easily defensible locations. In addition to the loss of life, the colonists also lost valuable crops and supplies necessary to survive the winter.

The warriors struck down the colonists with their own hammers and hatchets, they burned houses, killed livestock, scattered possessions, and mutilated the dead and dying before fleeing. The settlement of Wolstenholme Towne was ‘ruinated and spoyled’ by the Indian assault and suffered the highest death toll of any settlement during the uprising.

Although the official number of Virginia colonists killed was recorded at 347, some settlements, such as Bermuda Hundred, did not send in a report, so the number of dead was probably higher. Among the forgotten victims of the attack were the missing women of Martin’s Hundred plantation. Twenty female colonists, were the only captives taken by the Powhatans in the uprising. Few details of their ordeal have survived, and information about their lives is almost nonexistent. It is certain, however, that these women witnessed the violent deaths of neighbors and loved ones before being abducted. The dazed and despairing survivors had every reason to believe that those missing had either been killed in inaccessible areas, hacked or burned beyond recognition, or captured, which they believed would lead to certain death. In the weeks and months following the Powhatan onslaught, neither the Virginia Company officials nor the survivors of Martin’s Hundred attempted to locate and recover the missing settlers, staying alive took precedence over a hunt for neighbors they thought were beyond rescue. A year after the uprising, Richard Frethorne, a settler in Wolstenholme Towne, reported that the Powhatans held 15 people from that plantation in their villages, while another source indicated that there were ’19 English persons retayned “ . . in great slavery’ among the Indians and that ‘there were none but women in Captivitie . . . for the men they tooke they putt . . . to death.”

The Indian raids suddenly and shockingly transformed Virginia into a ‘labyrinth of melancholy,’ a severely wounded colony struggling to survive. The loss was so great that Martin’s Hundred and many other settlements were temporarily abandoned.

An English expedition along the Potomac River had received a message in late June or early July 1622 from Mistress Boyse, ‘a prisoner with nineteene more’ of the Powhatans. Mistress Boyse, who pleaded for the governor to try to secure the captives’ release, was the wife of either John Boyse, who had represented Martin’s Hundred in the first Virginia legislature of 1619, Thomas Boyse of the same plantation, who was listed among those killed in the March 1622 attack. With her at the Indian stronghold were Mistress Jeffries, wife of Nathaniel Jeffries who survived the uprising, and Jane Dickenson, wife of Ralph Dickenson, an indentured servant slain in the assault.

While their former neighbors feared new attacks, the captive women were placed in almost constant jeopardy by the fierce and frequent English raids on the Powhatans. Lodged as they were with Opechancanough, who was the prime target of retaliation, the English women, like their captors, endured hasty retreats, burning villages, and hunger caused by lost corn harvests.

The colonists’ retaliatory raids in the summer and fall of 1622 were so successful that Opechancanough, who had been unprepared for such massive offensives, decided in desperation to negotiate with his enemies, using the captured women as his trump card. In March 1623, he sent a message to Jamestown stating that enough blood had beenshed, and that because many of his people were starving he desired a truce to allow the Powhatans to plant corn for the coming year. In exchange for this temporary truce, Opechancanough promised to return the English women. To emphasize his sincerity, he sent Mistress Boyse to Jamestown a week later. When she rejoined her countrymen she was dressed like an Indian ‘Queen,’ in attire that probably would have included native pearl necklaces, copper medallions, various furs and feathers, and deerskin dyed red. Boyse was the only woman sent back at this time, and she remained the sole returned captive for many months. For the present, colony officials felt that killing hostile Indians took precedence over saving English prisoners, and they never intended to honor the truce in good faith. However, the Powhatans were allowed to plant spring corn to lessen their suspicions.

Baby Mary Jordan probably had no memory of that fateful day of the vernal equinox, 22 March 1622, when the Great Indian Massacre fell on the colony “like a thunderbolt”.

In 1622 the Second Anglo-Powhatan War began. Its origins are disputed. Some say that Opchanacanough initiated the war, Others argue that Opchanacanough had secured concessions from Governor Yeardley which the company would not accept. Thus Opchanacanough attack on March 22, 1622 may have been an attempt to defeat the colony before reinforcements arrived. Either way, the Virginia Company quickly published an account of this attack and massacre was the work of providence in that it gave an justifiable excuse for the complete genocide of the Powhatan, and the building of settlements on their former towns. New orders called for a "perpetual war without peace or truce" "to root out from being any longer a people, so cursed a nation, ungratefull to all benefitte, and incapable of all goodnesses."

The colonists’ retaliatory raids in the summer and fall of 1622 were so successful that Opechancanough, who had been unprepared for such massive offensives, decided in desperation to negotiate with his enemies, using the captured women as his trump card. In March 1623, he sent a message to Jamestown stating that enough blood had beenshed, and that because many of his people were starving he desired a truce to allow the Powhatans to plant corn for the coming year. In exchange for this temporary truce, Opechancanough promised to return the English women. To emphasize his sincerity, he sent Mistress Boyse to Jamestown a week later. When she rejoined her countrymen she was dressed like an Indian ‘Queen,’ in attire that probably would have included native pearl necklaces, copper medallions, various furs and feathers, and deerskin dyed red. Boyse was the only woman sent back at this time, and she remained the sole returned captive for many months. For the present, colony officials felt that killing hostile Indians took precedence over saving English prisoners, and they never intended to honor the truce in good faith. However, the Powhatans were allowed to plant spring corn to lessen their suspicions.

Baby Mary Jordan probably had no memory of that fateful day of the vernal equinox, 22 March 1622, when the Great Indian Massacre fell on the colony “like a thunderbolt”.

In 1622 the Second Anglo-Powhatan War began. Its origins are disputed. Some say that Opchanacanough initiated the war, Others argue that Opchanacanough had secured concessions from Governor Yeardley which the company would not accept. Thus Opchanacanough attack on March 22, 1622 may have been an attempt to defeat the colony before reinforcements arrived. Either way, the Virginia Company quickly published an account of this attack and massacre was the work of providence in that it gave an justifiable excuse for the complete genocide of the Powhatan, and the building of settlements on their former towns. New orders called for a "perpetual war without peace or truce" "to root out from being any longer a people, so cursed a nation, ungratefull to all benefitte, and incapable of all goodnesses."

Jordan's Journey was a stronghold of the colony. After the Massacre, "Master Samuel Jordan gathered together but a few of the stragglers about him at 'Beggar's Bush' where he fortified himself and lived in “despight of the enemy." Governor Wyatt wrote to the Virginia Company back in London, April 1622, "that he thought fit to hold a few outlying places, including the plantation of Mr. Samuel Jordan; but to abandon others and concentrate the colonists at Jamestown."

Beggar’s Bush had provided a formidable defense against the Indian attack. After the attack, Samuel gathered together some of the survivors into Beggar's Bush. At the time of a survey in 1623, Beggar's Bush housed 42 people, including many neighboring families who had gone there for protection. Although the consequences of the Indian attack were not enough to threaten the extermination of the Colony, they were deeply destructive. Many plantations were forced to be abandoned and safety became the principal order of the day.

Ironically, during the end of that same year, during the winter of 1622-23 the colonists were forced to trade with the Indians for corn and supplies and even with these provisions many went hungry. The mortality rate during the winter of 1622-23 climbed due to malnutrition and disease - over four hundred settlers died.

In May 1623 the colonists arranged a spurious peace parley with Opechancanough through friendly Indian intermediaries. On May 22, Captain William Tucker and a force of musketeers met with Opechancanough and other prominent Powhatans on neutral ground along the Potomac River, allegedly to negotiate the release of the other captives. But Tucker’s objective was the slaughter of Powhatan leaders. After the captain and the Indians had exchanged speeches, approximately 200 of the Powhatans who had accompanied their leaders unwittingly drank poisoned wine that Jamestown’s resident physician and later governor, Dr. John Pott, had prepared for the occasion. Many of the Indians fell sick or immediately dropped dead, and Tucker’s men shot and killed about 50 more. Some important tribal members were slain, but Opechancanough escaped, and with him went any hopes of a quick return for the captured women. Between May and November of that same year, the colonists ravaged the Powhatans throughout Tidewater Virginia. The ‘fraudulent peace’ had worked, and the Indians had planted corn ‘in great abundance’ only to see Englishmen harvest it for their own use. Successful raids by the settlers not only proved the undoing of the Powhatans but made fortunes for several Jamestown corn profiteers.

While the captive women suffered alongside their captors, the Indian war transformed the colony into an even cruder, crueler place than before. The war intensified the social stratification between leaders and laborers and masters and servants, while a handful of powerful men on Virginia Governor Sir Francis Wyatt’s council thoroughly dominated the political, economic, and military affairs of the colony. It soon became clear that the fate of the missing women depended not upon official concern or humanitarian instincts but upon the principle that everything and everybody had a price. Near the end of 1623, more than a year and a half after the uprising, the prosperous Dr. Pott ransomed Jane Dickenson and other women from the Indians for a few pounds of trade beads. After her release, Dickenson learned that she owed a debt of labor to Dr. Pott for the ransom he had paid and for the three years of service that her deceased husband had left on his contract of servitude at the time of his death. She complained bitterly that her new “servitude differeth not from her slavery with the Indians.” By 1624, no more than seven of the fifteen to twenty hostages had arrived in Jamestown.

Beggar’s Bush had provided a formidable defense against the Indian attack. After the attack, Samuel gathered together some of the survivors into Beggar's Bush. At the time of a survey in 1623, Beggar's Bush housed 42 people, including many neighboring families who had gone there for protection. Although the consequences of the Indian attack were not enough to threaten the extermination of the Colony, they were deeply destructive. Many plantations were forced to be abandoned and safety became the principal order of the day.

Ironically, during the end of that same year, during the winter of 1622-23 the colonists were forced to trade with the Indians for corn and supplies and even with these provisions many went hungry. The mortality rate during the winter of 1622-23 climbed due to malnutrition and disease - over four hundred settlers died.

In May 1623 the colonists arranged a spurious peace parley with Opechancanough through friendly Indian intermediaries. On May 22, Captain William Tucker and a force of musketeers met with Opechancanough and other prominent Powhatans on neutral ground along the Potomac River, allegedly to negotiate the release of the other captives. But Tucker’s objective was the slaughter of Powhatan leaders. After the captain and the Indians had exchanged speeches, approximately 200 of the Powhatans who had accompanied their leaders unwittingly drank poisoned wine that Jamestown’s resident physician and later governor, Dr. John Pott, had prepared for the occasion. Many of the Indians fell sick or immediately dropped dead, and Tucker’s men shot and killed about 50 more. Some important tribal members were slain, but Opechancanough escaped, and with him went any hopes of a quick return for the captured women. Between May and November of that same year, the colonists ravaged the Powhatans throughout Tidewater Virginia. The ‘fraudulent peace’ had worked, and the Indians had planted corn ‘in great abundance’ only to see Englishmen harvest it for their own use. Successful raids by the settlers not only proved the undoing of the Powhatans but made fortunes for several Jamestown corn profiteers.

While the captive women suffered alongside their captors, the Indian war transformed the colony into an even cruder, crueler place than before. The war intensified the social stratification between leaders and laborers and masters and servants, while a handful of powerful men on Virginia Governor Sir Francis Wyatt’s council thoroughly dominated the political, economic, and military affairs of the colony. It soon became clear that the fate of the missing women depended not upon official concern or humanitarian instincts but upon the principle that everything and everybody had a price. Near the end of 1623, more than a year and a half after the uprising, the prosperous Dr. Pott ransomed Jane Dickenson and other women from the Indians for a few pounds of trade beads. After her release, Dickenson learned that she owed a debt of labor to Dr. Pott for the ransom he had paid and for the three years of service that her deceased husband had left on his contract of servitude at the time of his death. She complained bitterly that her new “servitude differeth not from her slavery with the Indians.” By 1624, no more than seven of the fifteen to twenty hostages had arrived in Jamestown.

Proudly powered by Weebly