“With uncertain rumors of Gold in far-off California, a terra incognito lying somewhere near the sunset on the North American continent, first reaching the Atlantic states in October of 1848, little credence was given to the reports. But a when few persons returned from the placer diggings with specimens of gold, the adventurous spirit of young Americans was aroused regarding the location of this American El Dorado.

By December of 1848, the stories of gold being uncovered by the pound were confirmed beyond question by the shipments of this precious metal in payment for goods and supplies, ordered out from the east. Several vessels were at once put up for passengers and freight, by way of Cape Horn!”

– DR. J. C. Tucker 1849

By December of 1848, the stories of gold being uncovered by the pound were confirmed beyond question by the shipments of this precious metal in payment for goods and supplies, ordered out from the east. Several vessels were at once put up for passengers and freight, by way of Cape Horn!”

– DR. J. C. Tucker 1849

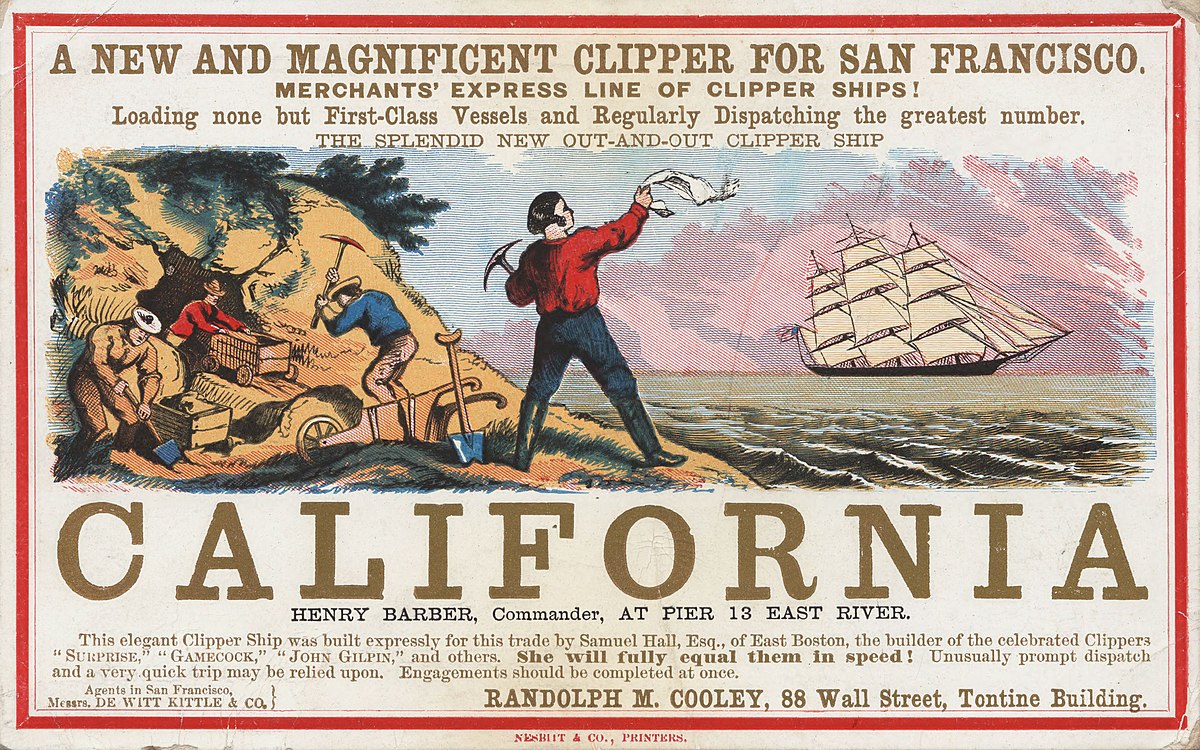

When President Polk acknowledged the gold finds in California in front of congress on December 5, 1848, overnight, men across the eastern seaboard frantically booked passage on any and every available ship.

A clipper was the model-type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had a large total sail area. The boom years of the clipper era began in 1843 in response to a growing demand for faster delivery of tea from China. This continued under the stimulating influence of the discovery of gold in California in 1848, and ended with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

Thus, the former cabin boy, now a 16-17 year old seasoned boatswain named James Jordan, found himself and his fellow sailors en route for the Pacific side of the America.

Nothing was ever recorded of his sailing exploits, where he been, the sights he saw. But, he must of shared great, wondrous stories with his grandchildren when they asked to see his tattoos from his sailing days as youth, which he would only allow them to see just for a few seconds at a time.

Ordinary fare to California would be $300 to $600 for paying passengers, but James on the other hand, was employed working on a Clipper merchant ship traveling south around the tip of Cape Horn, South America , heading to the new Mecca of the western hemisphere. Cape Horn marks the northern boundary of the Drake’s Passage and where the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans meet.

A clipper was the model-type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had a large total sail area. The boom years of the clipper era began in 1843 in response to a growing demand for faster delivery of tea from China. This continued under the stimulating influence of the discovery of gold in California in 1848, and ended with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

Thus, the former cabin boy, now a 16-17 year old seasoned boatswain named James Jordan, found himself and his fellow sailors en route for the Pacific side of the America.

Nothing was ever recorded of his sailing exploits, where he been, the sights he saw. But, he must of shared great, wondrous stories with his grandchildren when they asked to see his tattoos from his sailing days as youth, which he would only allow them to see just for a few seconds at a time.

Ordinary fare to California would be $300 to $600 for paying passengers, but James on the other hand, was employed working on a Clipper merchant ship traveling south around the tip of Cape Horn, South America , heading to the new Mecca of the western hemisphere. Cape Horn marks the northern boundary of the Drake’s Passage and where the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans meet.

The journey for these hopeful sea-faring adventurers would experienced the usual equatorial clams sailing south beneath the the clear starlights of the equator and a brighter gleam of the Southern Cross, catching the southeast trades. Then, a sighting the Rio Janeiro headlands a range of mountains that guarded the mouth of Rio's harbor, that could be seen from 30 miles out at sea. At the foot of these mountains spread out the very welcomed, tropical marble city of Rio de Janeiro. As they glided between the emerald green islands, passing an ancient Moorish-looking fortress, they had been traveling confined for 2 months in a crowded vessel.

Like a fairy dream, every sense was gratified. Seeing the deep green dense foliage, brilliant flowers and luscious fruits, towering palms with bent fringed foliage in graceful dignity. The deep blue sky, the clear softly rippling waves that lovingly caress the white sandy beaches.

While at the port in Rio other California bound vessels would also arrive. The local Hotel Farrrue would continually be over crowded with fortune-seeking Yankees and it never closed it’s doors. With fresh water, fruits and wine coming onboard the order was given by the captain, “Heave away your anchor” to the crew, and the the men responded “Anchored weighed sir”. Slowly gliding out of the harbor the good ship turned southward on a direct course for Cape Horn.

The run down the remainder on the South American coast was rapid and most likely without incident, with the usual shoal of dolphins the leaped and plunged beneath the ship’s bows. The sea would be luminous at night and the Southern Cross grew brighter and finally the “Magellan Clouds” that mysteriously constellated trinity of clouds that regularly rises and sets south of the Magellan Straits guided them forward.

The voyage was long, averaging six months. Fresh water and other supplies could be hard to get. The Straights of Magellan took three to six weeks to cross in narrow channels with unpredictable tides, winds and currents that could dash a wooden ship onto nearby rocks, stranding crew and passengers alike. Many of the brigs and schooners shunned the straight and opted to sail the cape itself. If the ship and its rigging stood up to the constant storms it could take a month or more of westward travel before they could swing north and head for California.

However, a sudden change of wind could easily drive you into currents and latitudes that would drastically end your voyage. Driven south 60 degrees, the icebergs are grandly magnificent when they are not too dangerously close. The decks and rigging would crystallized with ice, growing thicker by the day. With hatches battened down, the vessel pitching bows under the high seas and counter currents, knocking the headway out of any limited forward progress. The chances of slipping and going overboard were excellent, especially for those with frosted hands and feet. Buffeted by head winds, chop seas and there would be barely six hours of daylight for the next two weeks!

At that point, there would be unceasing, and heart-wrenching prayers falling from their lips for their crew consigned to get them through safely the cold, turbulent, and very perilous waters off Cape Horn. The days grew shorter, getting colder as they went. The previous days might have been beautifully clear, but not for long, suddenly fierce storms of wind and rain were upon them.

Like a fairy dream, every sense was gratified. Seeing the deep green dense foliage, brilliant flowers and luscious fruits, towering palms with bent fringed foliage in graceful dignity. The deep blue sky, the clear softly rippling waves that lovingly caress the white sandy beaches.

While at the port in Rio other California bound vessels would also arrive. The local Hotel Farrrue would continually be over crowded with fortune-seeking Yankees and it never closed it’s doors. With fresh water, fruits and wine coming onboard the order was given by the captain, “Heave away your anchor” to the crew, and the the men responded “Anchored weighed sir”. Slowly gliding out of the harbor the good ship turned southward on a direct course for Cape Horn.

The run down the remainder on the South American coast was rapid and most likely without incident, with the usual shoal of dolphins the leaped and plunged beneath the ship’s bows. The sea would be luminous at night and the Southern Cross grew brighter and finally the “Magellan Clouds” that mysteriously constellated trinity of clouds that regularly rises and sets south of the Magellan Straits guided them forward.

The voyage was long, averaging six months. Fresh water and other supplies could be hard to get. The Straights of Magellan took three to six weeks to cross in narrow channels with unpredictable tides, winds and currents that could dash a wooden ship onto nearby rocks, stranding crew and passengers alike. Many of the brigs and schooners shunned the straight and opted to sail the cape itself. If the ship and its rigging stood up to the constant storms it could take a month or more of westward travel before they could swing north and head for California.

However, a sudden change of wind could easily drive you into currents and latitudes that would drastically end your voyage. Driven south 60 degrees, the icebergs are grandly magnificent when they are not too dangerously close. The decks and rigging would crystallized with ice, growing thicker by the day. With hatches battened down, the vessel pitching bows under the high seas and counter currents, knocking the headway out of any limited forward progress. The chances of slipping and going overboard were excellent, especially for those with frosted hands and feet. Buffeted by head winds, chop seas and there would be barely six hours of daylight for the next two weeks!

At that point, there would be unceasing, and heart-wrenching prayers falling from their lips for their crew consigned to get them through safely the cold, turbulent, and very perilous waters off Cape Horn. The days grew shorter, getting colder as they went. The previous days might have been beautifully clear, but not for long, suddenly fierce storms of wind and rain were upon them.

The waters around Cape Horn are particularly hazardous, owing to strong winds, large waves, strong currents and icebergs. Notoriously known for treacherous williwaw winds, which can strike a vessel with little or no warning - given the narrowness of these routes, vessels have a significant risk of being driven onto the rocks. The open waters of the Drake Passage, south of Cape Horn, provide by far the widest route, at about 800 kilometres (500 miles) wide; this passage offers ample sea room for maneuvering as winds change, and is the route used by most ships and sailboats, despite the possibility of extreme wave conditions.

"Doubling the Horn" is traditionally understood to involve sailing from 50 degrees South on one coast to 50 degrees South on the other coast, the two benchmark latitudes of a Horn run, a considerably more difficult and time-consuming endeavor having a minimum length of 930 miles.

The prevailing winds in latitudes below 40° south can blow from west to east around the world almost uninterrupted by land, giving rise to the "roaring forties" and the even more wild "furious fifties" and "screaming sixties". These winds are hazardous enough that ships traveling east would tend to stay in the northern part of the forties (i.e. not far below 40° south latitude); however, rounding Cape Horn requires ships to press south to 56° south latitude, well into the zone of fiercest winds. These winds are exacerbated at the Horn by the funneling effect of the Andes and the Antarctic peninsula, which channel the winds into the relatively narrow Drake Passage.

These strong winds of the Southern Ocean give rise to correspondingly large waves; these waves can attain great height as they roll around the Southern Ocean, free of any interruption from land. At the Horn, however, these waves encounter an area of shallow water to the south of the Horn, which has the effect of making the waves shorter and steeper, greatly increasing the hazard to ships. If the strong eastward current through the Drake Passage encounters an opposing east wind, this can have the effect of further building up the waves. In addition to these "normal" waves, the area west of the Horn is particularly notorious for rogue waves, which can easily attain heights of up to 30 metres (98 feet).

Traditionally, a sailor who had rounded the Horn was entitled to wear a gold loop earring—in the left ear, the one which had faced the Horn in a typical eastbound passage—and to dine with one foot on the table; a sailor who had also rounded the Cape of Good Hope could place both feet on the table.

"Doubling the Horn" is traditionally understood to involve sailing from 50 degrees South on one coast to 50 degrees South on the other coast, the two benchmark latitudes of a Horn run, a considerably more difficult and time-consuming endeavor having a minimum length of 930 miles.

The prevailing winds in latitudes below 40° south can blow from west to east around the world almost uninterrupted by land, giving rise to the "roaring forties" and the even more wild "furious fifties" and "screaming sixties". These winds are hazardous enough that ships traveling east would tend to stay in the northern part of the forties (i.e. not far below 40° south latitude); however, rounding Cape Horn requires ships to press south to 56° south latitude, well into the zone of fiercest winds. These winds are exacerbated at the Horn by the funneling effect of the Andes and the Antarctic peninsula, which channel the winds into the relatively narrow Drake Passage.

These strong winds of the Southern Ocean give rise to correspondingly large waves; these waves can attain great height as they roll around the Southern Ocean, free of any interruption from land. At the Horn, however, these waves encounter an area of shallow water to the south of the Horn, which has the effect of making the waves shorter and steeper, greatly increasing the hazard to ships. If the strong eastward current through the Drake Passage encounters an opposing east wind, this can have the effect of further building up the waves. In addition to these "normal" waves, the area west of the Horn is particularly notorious for rogue waves, which can easily attain heights of up to 30 metres (98 feet).

Traditionally, a sailor who had rounded the Horn was entitled to wear a gold loop earring—in the left ear, the one which had faced the Horn in a typical eastbound passage—and to dine with one foot on the table; a sailor who had also rounded the Cape of Good Hope could place both feet on the table.

Like an ascent of Mount Everest, sailing around Cape Horn earns you a place amongst the elite and with good reason. Before the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, Cape Horn was a place that gave mariners nightmares. The waters off this rocky point, at the southern tip of Chile’s Tierra del Fuego peninsula, pose a perfect storm of hazards.

Southwest of Cape Horn, the ocean floor rises sharply from 4,020 meters (13,200 feet) to 100 meters (330 feet) within a few kilometers. This sharp difference, combined with the potent westerly winds that swirl around the Furious Fifties, pushes up massive waves with frightening regularity. Add in frigid water temperatures, rocky coastal shoals, and stray icebergs—which drift north from Antarctica across the Drake Passage—and it is easy to see why the area is known as a graveyard for ships.

Southwest of Cape Horn, the ocean floor rises sharply from 4,020 meters (13,200 feet) to 100 meters (330 feet) within a few kilometers. This sharp difference, combined with the potent westerly winds that swirl around the Furious Fifties, pushes up massive waves with frightening regularity. Add in frigid water temperatures, rocky coastal shoals, and stray icebergs—which drift north from Antarctica across the Drake Passage—and it is easy to see why the area is known as a graveyard for ships.

What must have seemed a terrifying experience and and endless eternity, eventually, time past and the days would grow longer. And the warm sunny atmosphere of the south Pacific thawed the passengers out. Upon reaching Valparaiso, Chile, the California bound vessels would run into ships returning to the east coast, with stories young prospectors unearthing $10,000. In just two weeks.

Crossing the “line” again and receiving the customary visit from “Father Neptune” announcing the meridian.

Finally, it was Acapulco, the last port before reaching California.

Crossing the “line” again and receiving the customary visit from “Father Neptune” announcing the meridian.

Finally, it was Acapulco, the last port before reaching California.

1850 - San Francisco Bay with Telegraph Hill in the background

Proudly powered by Weebly