On to Oregon

The provisional government allotted 640 acres of fertile Oregon farmland to every male citizen willing to relocate to the Oregon territory. The Emigrants had three major fears—Indians, disease, and the weather. It is estimated that 34,000 emigrants died along the Oregon Trail — averaging 17 deaths per mile. A good wagon outfit could haul about a ton. Its wooden box was 4 feet wide by 10 to 12 feet long.

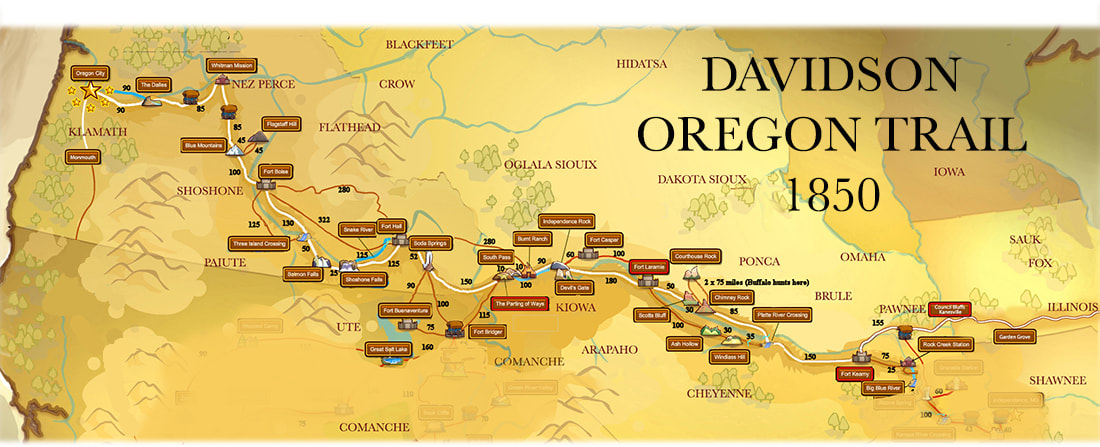

The Oregon Trail extended from the Missouri River to the Willamette River and was used by nearly 400,000 people. It crossed nearly 2,000 miles of plains, deserts, canyons, and mountains, so unfamiliar and inhospitable that it was dangerous to pause, and unthinkable to settle. It was a five to six months' journey which had to begin in early May in order to avoid being trapped by mountain snowstorms. In the 1840s, guidebooks in book or pamphlet form were available for emigrants. Some provided reliable information. All contributed to the "Oregon Fever" that swept the country.

Wagon trains coming out of Independence, Missouri, formed lines three quarters of a mile in length. Families alternated their places in line each day, with those at the end having to "eat dust."

The teamsters drove their wagons or walked beside their teams. Mules or oxen were preferred over horses to pull the wagons. Women and children were usually on foot. The men were generally on horseback, herding cattle and other animals. Wagon trains averaged 12 to 15 miles a day. At night the wagons were grouped into a circle to corral the animals.

The most widely-read book about the Oregon Trail was that of Francis Parkman. He rode from Independence to Fort Laramie, keeping a daily diary.

"As we pushed rapidly by the wagons, children's faces were thrust out from the white coverings to look at us; while the care-worn, thin-featured matron, or the buxom girl, seated in front, suspended the knitting on which most of them were engaged, to stare at us with wondering curiosity. By the side of each wagon stalked the proprietor, urging on his patient oxen, who shouldered heavily along, inch by inch, on their interminable journey. It was easy to see that fear and dissension prevailed among them; some of the men...looked wistfully upon us as we rode lightly and swiftly by...."

--Francis Parkman, The Oregon Trail.

Each part of the journey had its set of unique difficulties. During the first third of the journey across the plains, emigrants got used to the routine and work of travel. Then they set out on the steep ascent to the Continental Divide; water, fuel, grass for the livestock, fresh meat, and food staples became scarce. The final third was the most difficult part of the trail as they crossed both the Blue Mountains in eastern Oregon and the Cascades to the west.

Until the Barlow Road across the Cascades was opened as a toll road the only choice for the emigrants was to go down the Columbia from The Dalles on a raft or abandon their wagons and build boats.

Emigrants had three major fears - Indians, disease, and the weather. Indians proved to be the least dangerous. Accidents and rampant diseases (especially cholera) killed many more Oregon travelers than did Indians. It is estimated that 34,000 emigrants died along the trail — averaging 17 deaths per mile.

The Butler, Davidson and Murphy families sent as an advance party to prepare the way for a larger migration of settlers that would come overland in 1852 and 1853.

In the early 1830s, several of these families, all strong Christians committed to the Restoration Movement, had migrated from Barren and Warren counties in southern Kentucky to establish Warren County in northwestern Illinois. They had their church roots in the Mulkey and Stone movements, but they had recently become aware of Alexander Campbell.

In the late 1840s, several families in the Butler-Davidson- Murphy orbit developed an exceptionally severe case of "Oregon Fever." Between 1846 and 1850 many meetings were held in the home of Ira F. M. Butler to discuss plans for a large migration to the Willamette Valley. It took a great deal of persuasion to get the women to see the advantages of such a difficult move, and when they finally consented, it was with the understanding that certain specific conditions would be met.

The women exacted from their men a promise that a school and a church would be established before they consented to going, noted one account. "The school would be patterned after Bethany College in Virginia which was founded by Alexander Campbell, and would be a school 'where men and women alike might be schooled in the science of living and in the fundamental principles of religion.'

Davidson Wagon Train of 1850: (Partial List)

From Monmouth, Illinois to Monmouth, Oregon

10 wagons, 39 persons, 80 oxen and cows and several American breed (Morgan) horses.

Elijah Davidson, (age 67) (son of Alexander Davidson)

Margaret Murphy, (age 64)

Elijah Barton Davidson, Jr., (age 31) son of Elijah & Margaret Davidson

Saloma (Jones) Davidson, wife (age 28)

Ivory Quinby Davidson (age 7)

Isaac G. Davidson (age 5)

John S. Davidson (age 3)

Elijah Jones Davidson (age 1)

Alexander Bridges Davidson, single (age 22) son of Elijah & Margaret Davidson

George Washington DeWeese (age33)

Rachel Davidson Deweese (age 29)

Carlin Deweese (age 10)

Sarah Deweese (age7)

William Deweese (newborn)

Squire Stoten Whitman (age22)

Elizabeth (Davidson) Whitman, (age 27) wife and daughter of Elijah & Margaret Davidson

Mary Ann Whitman, (age 10)

John Murphy Whitman, (age 9)

William A. Whitman, (age 6)

Martha J. Whitman, (age 3)

Margaret Ardene Whitman (age 1)

Thomas Hartzell Lucas (age26)

Sarah H. (Davidson) Lucas, (age25) wife and daughter of Elijah & Margaret Davidson

Smith W. Lucas, (age4)

Amanda Lucas (age2)

Marsham Albert Lucas born on westbound wagon train in Iowa 22 April 1850,

Josiah Whitman (age 38)

Hanna Davidson Whitman - wife (age 41) daughter of Elijah & Margaret Davidson

Permelia Emma Whitman (age 17)

Margaret Davidson Whitman (age 15)

Hulda C. Whitman (age 13)

Elijah Butler, returned to Illinois in 1851, recrossed in 1852

Isaac Butler, returned to Illinois in 1851, recrossed in 1852

Mr. and Mrs. Calhorn

Ethan Calhorn

Allen Calhorn

Shirley Calhorn

William Jones

Elijah Jones, with his wife and children

Peter Shelton

Stephen White

Able White

James Sisson

John Smith

Isaac Grundy

The provisional government allotted 640 acres of fertile Oregon farmland to every male citizen willing to relocate to the Oregon territory. The Emigrants had three major fears—Indians, disease, and the weather. It is estimated that 34,000 emigrants died along the Oregon Trail — averaging 17 deaths per mile. A good wagon outfit could haul about a ton. Its wooden box was 4 feet wide by 10 to 12 feet long.

The Oregon Trail extended from the Missouri River to the Willamette River and was used by nearly 400,000 people. It crossed nearly 2,000 miles of plains, deserts, canyons, and mountains, so unfamiliar and inhospitable that it was dangerous to pause, and unthinkable to settle. It was a five to six months' journey which had to begin in early May in order to avoid being trapped by mountain snowstorms. In the 1840s, guidebooks in book or pamphlet form were available for emigrants. Some provided reliable information. All contributed to the "Oregon Fever" that swept the country.

Wagon trains coming out of Independence, Missouri, formed lines three quarters of a mile in length. Families alternated their places in line each day, with those at the end having to "eat dust."

The teamsters drove their wagons or walked beside their teams. Mules or oxen were preferred over horses to pull the wagons. Women and children were usually on foot. The men were generally on horseback, herding cattle and other animals. Wagon trains averaged 12 to 15 miles a day. At night the wagons were grouped into a circle to corral the animals.

The most widely-read book about the Oregon Trail was that of Francis Parkman. He rode from Independence to Fort Laramie, keeping a daily diary.

"As we pushed rapidly by the wagons, children's faces were thrust out from the white coverings to look at us; while the care-worn, thin-featured matron, or the buxom girl, seated in front, suspended the knitting on which most of them were engaged, to stare at us with wondering curiosity. By the side of each wagon stalked the proprietor, urging on his patient oxen, who shouldered heavily along, inch by inch, on their interminable journey. It was easy to see that fear and dissension prevailed among them; some of the men...looked wistfully upon us as we rode lightly and swiftly by...."

--Francis Parkman, The Oregon Trail.

Each part of the journey had its set of unique difficulties. During the first third of the journey across the plains, emigrants got used to the routine and work of travel. Then they set out on the steep ascent to the Continental Divide; water, fuel, grass for the livestock, fresh meat, and food staples became scarce. The final third was the most difficult part of the trail as they crossed both the Blue Mountains in eastern Oregon and the Cascades to the west.

Until the Barlow Road across the Cascades was opened as a toll road the only choice for the emigrants was to go down the Columbia from The Dalles on a raft or abandon their wagons and build boats.

Emigrants had three major fears - Indians, disease, and the weather. Indians proved to be the least dangerous. Accidents and rampant diseases (especially cholera) killed many more Oregon travelers than did Indians. It is estimated that 34,000 emigrants died along the trail — averaging 17 deaths per mile.

The Butler, Davidson and Murphy families sent as an advance party to prepare the way for a larger migration of settlers that would come overland in 1852 and 1853.

In the early 1830s, several of these families, all strong Christians committed to the Restoration Movement, had migrated from Barren and Warren counties in southern Kentucky to establish Warren County in northwestern Illinois. They had their church roots in the Mulkey and Stone movements, but they had recently become aware of Alexander Campbell.

In the late 1840s, several families in the Butler-Davidson- Murphy orbit developed an exceptionally severe case of "Oregon Fever." Between 1846 and 1850 many meetings were held in the home of Ira F. M. Butler to discuss plans for a large migration to the Willamette Valley. It took a great deal of persuasion to get the women to see the advantages of such a difficult move, and when they finally consented, it was with the understanding that certain specific conditions would be met.

The women exacted from their men a promise that a school and a church would be established before they consented to going, noted one account. "The school would be patterned after Bethany College in Virginia which was founded by Alexander Campbell, and would be a school 'where men and women alike might be schooled in the science of living and in the fundamental principles of religion.'

Davidson Wagon Train of 1850: (Partial List)

From Monmouth, Illinois to Monmouth, Oregon

10 wagons, 39 persons, 80 oxen and cows and several American breed (Morgan) horses.

Elijah Davidson, (age 67) (son of Alexander Davidson)

Margaret Murphy, (age 64)

Elijah Barton Davidson, Jr., (age 31) son of Elijah & Margaret Davidson

Saloma (Jones) Davidson, wife (age 28)

Ivory Quinby Davidson (age 7)

Isaac G. Davidson (age 5)

John S. Davidson (age 3)

Elijah Jones Davidson (age 1)

Alexander Bridges Davidson, single (age 22) son of Elijah & Margaret Davidson

George Washington DeWeese (age33)

Rachel Davidson Deweese (age 29)

Carlin Deweese (age 10)

Sarah Deweese (age7)

William Deweese (newborn)

Squire Stoten Whitman (age22)

Elizabeth (Davidson) Whitman, (age 27) wife and daughter of Elijah & Margaret Davidson

Mary Ann Whitman, (age 10)

John Murphy Whitman, (age 9)

William A. Whitman, (age 6)

Martha J. Whitman, (age 3)

Margaret Ardene Whitman (age 1)

Thomas Hartzell Lucas (age26)

Sarah H. (Davidson) Lucas, (age25) wife and daughter of Elijah & Margaret Davidson

Smith W. Lucas, (age4)

Amanda Lucas (age2)

Marsham Albert Lucas born on westbound wagon train in Iowa 22 April 1850,

Josiah Whitman (age 38)

Hanna Davidson Whitman - wife (age 41) daughter of Elijah & Margaret Davidson

Permelia Emma Whitman (age 17)

Margaret Davidson Whitman (age 15)

Hulda C. Whitman (age 13)

Elijah Butler, returned to Illinois in 1851, recrossed in 1852

Isaac Butler, returned to Illinois in 1851, recrossed in 1852

Mr. and Mrs. Calhorn

Ethan Calhorn

Allen Calhorn

Shirley Calhorn

William Jones

Elijah Jones, with his wife and children

Peter Shelton

Stephen White

Able White

James Sisson

John Smith

Isaac Grundy

At nearly 68 yrs. old, Elijah Davidson and family crossed the plains by ox team from Monmouth, Illinois, halting in the center of present-day Laurelhurst, suburb of Portland. Here in Laurelhurst, Elijah Jr, a preacher like his father, took up a 160 acre donation claim. The family train continued south into the Willamette Valley. The Davidson wagon train made the trip in less than 5 months.

However, Portland was a wild and hard drinking town of pioneers, prostitutes and gold prospectors, not ideal for Christian family living. Elijah Jr. sold the donation claim for the sum of $500, moved southward into the Willamette Valley to help build a new town and build a Christian college. This great green bowl, encircled by mountainous walls, was more like the "Oregon" they expected to find.

"Its sheltered situation, embosomed in mountains, renders it good pasturing ground in the winter time; when the elk come down to it in great numbers, driven out of the mountains by the snow. The Indians then resort to it to hunt. They likewise come to it in the summer to dig the camash root, of which it produces immense quantities. When this plant is in blossom, the whole valley is tinted by its blue flowers, and looks like the ocean when overcast by a cloud."

1850 An estimated 65,000 people took to the trail, mostly due to the California Gold Rush. This was also on of the more disastrous years of the migration with perhaps 5,000 deaths, mostly caused by cholera.

The Davidson Wagon Train headed due west out of Monmouth Ill., towards Nauvoo. After crossing the Mississippi River into Iowa, they followed the old Mormon Trail across Iowa to Kanesville IA. There they were ferried over the Missouri River to Council Bluff, NEB.

While Independence, MO. was the more popular "jumping off" point on the Oregon Trail. Here at Council Bluff, the emigrants stocked up on supplies and prepared their wagons. There was generally a festive air in Independence in the spring. The newcomers collected information and misinformation, made friends and enemies, changed proposed destinations, and behaved in general as though they were on a picnic. Because of the fear of Indian attacks (which was largely unfounded), emigrants often tried organize a traveling party here, because no one wanted to head west alone.

Still following the Mormon Trail down to Fort Kearny, where the trail joined the Oregon Trail (aka Immigrant Trail) all the way to Oregon. Just outside Fort Kearny, they most likely joined with other wagon trains heading west for security reasons. During the peak travel season Fort Kearny would witness five-hundred wagons passing by everyday.

At the outset, wagon trains would write out a constitution -- a set of by-laws that all members of the train were expected to follow. This was common practice on the Oregon Trail, but not many of these high-minded by-laws survived their first brush with the difficulties of life on the Trail. The wagon trains would also organize a squad of armed men who could be detached from the wagon train in case of emergency. They were usually called on to hunt for lost livestock or missing members of the wagon train, but they could also play a role in quelling the violence.

Oregon Trail Diaries:

“After a particular route has been selected to make the journey across the plains, and the requisite number have arrived . . . their first business should be to organize themselves into a company and elect a commander. The company should be of sufficient magnitude to herd and guard animals, and for protection against Indians. An obligation should be drawn up and signed by all the members of the association, wherein each one should bind himself to abide in all cases by the orders and decisions of the captain and to aid him by every means in this power.”

Capt. R. B. Marcy

Fort Kearny, was established in the spring of 1848 "near the head of the Grand Island" along the Platte River. Ft. Kearny was the first military post built to protect the Oregon Trail emigrants. The fort remained an important wayside throughout the emigration period. Many pioneers would purchased food at the fort, and nearly everyone took advantage of the fort's reliable mail service. In late May as many as 2,000 emigrants and 10,000 oxen might pass through in a single day.

Ft. Kearny was not the walled fortification that many pioneers expected. It was instead a collection of ramshackle buildings, most made of sod. The construction was so crude that snakes often slithered through the walls and into the beds of the soldiers stationed there.

However, Portland was a wild and hard drinking town of pioneers, prostitutes and gold prospectors, not ideal for Christian family living. Elijah Jr. sold the donation claim for the sum of $500, moved southward into the Willamette Valley to help build a new town and build a Christian college. This great green bowl, encircled by mountainous walls, was more like the "Oregon" they expected to find.

"Its sheltered situation, embosomed in mountains, renders it good pasturing ground in the winter time; when the elk come down to it in great numbers, driven out of the mountains by the snow. The Indians then resort to it to hunt. They likewise come to it in the summer to dig the camash root, of which it produces immense quantities. When this plant is in blossom, the whole valley is tinted by its blue flowers, and looks like the ocean when overcast by a cloud."

1850 An estimated 65,000 people took to the trail, mostly due to the California Gold Rush. This was also on of the more disastrous years of the migration with perhaps 5,000 deaths, mostly caused by cholera.

The Davidson Wagon Train headed due west out of Monmouth Ill., towards Nauvoo. After crossing the Mississippi River into Iowa, they followed the old Mormon Trail across Iowa to Kanesville IA. There they were ferried over the Missouri River to Council Bluff, NEB.

While Independence, MO. was the more popular "jumping off" point on the Oregon Trail. Here at Council Bluff, the emigrants stocked up on supplies and prepared their wagons. There was generally a festive air in Independence in the spring. The newcomers collected information and misinformation, made friends and enemies, changed proposed destinations, and behaved in general as though they were on a picnic. Because of the fear of Indian attacks (which was largely unfounded), emigrants often tried organize a traveling party here, because no one wanted to head west alone.

Still following the Mormon Trail down to Fort Kearny, where the trail joined the Oregon Trail (aka Immigrant Trail) all the way to Oregon. Just outside Fort Kearny, they most likely joined with other wagon trains heading west for security reasons. During the peak travel season Fort Kearny would witness five-hundred wagons passing by everyday.

At the outset, wagon trains would write out a constitution -- a set of by-laws that all members of the train were expected to follow. This was common practice on the Oregon Trail, but not many of these high-minded by-laws survived their first brush with the difficulties of life on the Trail. The wagon trains would also organize a squad of armed men who could be detached from the wagon train in case of emergency. They were usually called on to hunt for lost livestock or missing members of the wagon train, but they could also play a role in quelling the violence.

Oregon Trail Diaries:

“After a particular route has been selected to make the journey across the plains, and the requisite number have arrived . . . their first business should be to organize themselves into a company and elect a commander. The company should be of sufficient magnitude to herd and guard animals, and for protection against Indians. An obligation should be drawn up and signed by all the members of the association, wherein each one should bind himself to abide in all cases by the orders and decisions of the captain and to aid him by every means in this power.”

Capt. R. B. Marcy

Fort Kearny, was established in the spring of 1848 "near the head of the Grand Island" along the Platte River. Ft. Kearny was the first military post built to protect the Oregon Trail emigrants. The fort remained an important wayside throughout the emigration period. Many pioneers would purchased food at the fort, and nearly everyone took advantage of the fort's reliable mail service. In late May as many as 2,000 emigrants and 10,000 oxen might pass through in a single day.

Ft. Kearny was not the walled fortification that many pioneers expected. It was instead a collection of ramshackle buildings, most made of sod. The construction was so crude that snakes often slithered through the walls and into the beds of the soldiers stationed there.

Independence Rock on the Oregon Trail

William Sublette and his supply train party for the 1830 Rendezvous celebrated Independence Day there on July 4th, 1830. Independence Rock supposedly received its name at that time. The Oregon Pioneers considered Independence Rock as being halfway to Oregon. If Independence Rock was reached by July 4th, chances were good that the emigrants could reach the Oregon Country before snow fall.

Stampedes were a common problem on the Oregon Trail, and in hope of preventing them, many trains did not permit emigrants to bring dogs with them, as the cattle could easily be spooked by a playful or poorly-trained dog.

“We hear the Kennedy train had another stampede. They had just buried the baby of the women who died a few days ago and were just digging a grave for another woman who died. She was run over the cattle and wagons when the cattle stampeded yesterday. She lived twenty-four hours. She gave birth to a child a short time before she died. The child was buried with her. She leaves a little two year old girl and a husband. They say he is nearly crazy with sorrow. After cattle have been frightened once or twice there is no safety with them. Yesterday there were several loose horses came running up when the train of cattle started pell-mell, crippling two men besides killing the woman. ... I never supposed that cattle would run so in yoke and hitched to a wagon.”

“...no one knows why [the cattle] started to run. Some supposing it was the dogs and were afraid they might scare them again. So the company held a election and passed a dog law that every dog in the train was to be killed in 30 minutes.”

- James Scott McClung, August 3, 1862

After the "dog law" passed in the Kennedy wagon train, it was enough to alienate a few of its members and cause them to leave in search of a dog-friendly train -- not the first time and probably not the last that a wagon train was divided over the question of whether or not to kill the dogs traveling with it. The Ellis family remained with Captain Kennedy, and a week later they found themselves caught up in a violent encounter with the Shoshone Indians.

Most Indians were tolerant of the pioneer wagon trains that drove through their lands. Some traded and swapped buffalo robes and moccasins for knives, clothes, food and other items. Some tribes were notorious for stealing from the emigrants along the road. And, there were some violent altercations between Indians and pioneers, but these were very few compared with the total number of settlers who traveled in safety through Indian lands. In the early years of the trail, Indians never attacked a large wagon train, but stragglers could be in big trouble

Of the emigrants killed by Indians, about 90% were killed west of South Pass, mostly along the Snake and Humboldt Rivers or on the Applegate Trail to the southern end of the Willamette Valley. The Sioux, Shoshone, Kiowa, Crow, Ute, Paiute, were some of the various tribes that an emigrant train might encounter. Many of the depredations done by Shoshone Indians were on the stretch between Soda Springs/Ft. Hall and Snake River where it runs through what is now southern Idaho.

In the Kennedy wagon train, news of the fighting arrived about midday on August 9th when a lone rider thundered into camp while they were crossing the Snake River below American Falls. A few miles up the Trail, two other wagon trains were under attack. One was able to conduct a running fight to Massacre Rocks, where they holed up and defended themselves; the other train was overwhelmed and looted. Captain Kennedy dispatched some men to investigate, and when they arrived at the looted wagon train they found one emigrant killed, two wounded, several missing, and the wagons all without teams. Taking the wagons in tow, the men escorted the survivors to the others, where the rest of the Kennedy train soon joined them. -- totalling about 200 wagons and over 700 people

The following day, some of the men from the other wagon trains set out to recapture the oxen stolen by the Indians, but the Shoshones fought them off and pinned the emigrants in a grove of juniper trees atop a low ridge overlooking the Oregon Trail. Two were killed, and two more men were missing by the time they reached the shelter of the junipers. They were stuck there until another wagon train came by and covered their escape.

By the morning of August 11, there were five wagon trains huddled around the rocks – later named Massacre Rocks, an entirely inappropriate name that was probably coined more than fifty years later by local residents, incidentally, as there was never a massacre there. The presence of so many armed men discouraged further harassment by the Indians, giving the emigrants time to bury their dead before moving on.

“Miss Adams, the lady who was wounded in the fight with the Indians, died last night and was buried this morning. Some of the trains take the California Road this morning. We keep the old Oregon road.”

- Hamilton Scott, August 12, 1862

The incident at Massacre Rocks was the only serious trouble with Indians that the Kennedy train was involved with. Years later, one member of the wagon train asserted that their good fortune was a result of the train's consensus never to break the Sabbath by traveling on Sunday. The Kennedy train was on the road for another month and a half before arriving at their final destination.

Approaching Three Island Crossing (of the Snake River) meant the emigrants had a difficult choice. They could make a dangerous river crossing here for a direct route to Ft. Boise or stay on the south side of the Snake and follow the river around the bend. About half made the decision to cross using the three islands in the Snake as stepping stones. It would not be easy.

"We lost 2 of our men, Ayres and Stringer. Ayres got into trouble with his mules in crossing the stream. Stringer, who was about thirty, went to his relief, and both were drowned in sight of their women folks. The bodies were never recovered."

Emigrant Samuel Hancock, 1852

William Sublette and his supply train party for the 1830 Rendezvous celebrated Independence Day there on July 4th, 1830. Independence Rock supposedly received its name at that time. The Oregon Pioneers considered Independence Rock as being halfway to Oregon. If Independence Rock was reached by July 4th, chances were good that the emigrants could reach the Oregon Country before snow fall.

Stampedes were a common problem on the Oregon Trail, and in hope of preventing them, many trains did not permit emigrants to bring dogs with them, as the cattle could easily be spooked by a playful or poorly-trained dog.

“We hear the Kennedy train had another stampede. They had just buried the baby of the women who died a few days ago and were just digging a grave for another woman who died. She was run over the cattle and wagons when the cattle stampeded yesterday. She lived twenty-four hours. She gave birth to a child a short time before she died. The child was buried with her. She leaves a little two year old girl and a husband. They say he is nearly crazy with sorrow. After cattle have been frightened once or twice there is no safety with them. Yesterday there were several loose horses came running up when the train of cattle started pell-mell, crippling two men besides killing the woman. ... I never supposed that cattle would run so in yoke and hitched to a wagon.”

“...no one knows why [the cattle] started to run. Some supposing it was the dogs and were afraid they might scare them again. So the company held a election and passed a dog law that every dog in the train was to be killed in 30 minutes.”

- James Scott McClung, August 3, 1862

After the "dog law" passed in the Kennedy wagon train, it was enough to alienate a few of its members and cause them to leave in search of a dog-friendly train -- not the first time and probably not the last that a wagon train was divided over the question of whether or not to kill the dogs traveling with it. The Ellis family remained with Captain Kennedy, and a week later they found themselves caught up in a violent encounter with the Shoshone Indians.

Most Indians were tolerant of the pioneer wagon trains that drove through their lands. Some traded and swapped buffalo robes and moccasins for knives, clothes, food and other items. Some tribes were notorious for stealing from the emigrants along the road. And, there were some violent altercations between Indians and pioneers, but these were very few compared with the total number of settlers who traveled in safety through Indian lands. In the early years of the trail, Indians never attacked a large wagon train, but stragglers could be in big trouble

Of the emigrants killed by Indians, about 90% were killed west of South Pass, mostly along the Snake and Humboldt Rivers or on the Applegate Trail to the southern end of the Willamette Valley. The Sioux, Shoshone, Kiowa, Crow, Ute, Paiute, were some of the various tribes that an emigrant train might encounter. Many of the depredations done by Shoshone Indians were on the stretch between Soda Springs/Ft. Hall and Snake River where it runs through what is now southern Idaho.

In the Kennedy wagon train, news of the fighting arrived about midday on August 9th when a lone rider thundered into camp while they were crossing the Snake River below American Falls. A few miles up the Trail, two other wagon trains were under attack. One was able to conduct a running fight to Massacre Rocks, where they holed up and defended themselves; the other train was overwhelmed and looted. Captain Kennedy dispatched some men to investigate, and when they arrived at the looted wagon train they found one emigrant killed, two wounded, several missing, and the wagons all without teams. Taking the wagons in tow, the men escorted the survivors to the others, where the rest of the Kennedy train soon joined them. -- totalling about 200 wagons and over 700 people

The following day, some of the men from the other wagon trains set out to recapture the oxen stolen by the Indians, but the Shoshones fought them off and pinned the emigrants in a grove of juniper trees atop a low ridge overlooking the Oregon Trail. Two were killed, and two more men were missing by the time they reached the shelter of the junipers. They were stuck there until another wagon train came by and covered their escape.

By the morning of August 11, there were five wagon trains huddled around the rocks – later named Massacre Rocks, an entirely inappropriate name that was probably coined more than fifty years later by local residents, incidentally, as there was never a massacre there. The presence of so many armed men discouraged further harassment by the Indians, giving the emigrants time to bury their dead before moving on.

“Miss Adams, the lady who was wounded in the fight with the Indians, died last night and was buried this morning. Some of the trains take the California Road this morning. We keep the old Oregon road.”

- Hamilton Scott, August 12, 1862

The incident at Massacre Rocks was the only serious trouble with Indians that the Kennedy train was involved with. Years later, one member of the wagon train asserted that their good fortune was a result of the train's consensus never to break the Sabbath by traveling on Sunday. The Kennedy train was on the road for another month and a half before arriving at their final destination.

Approaching Three Island Crossing (of the Snake River) meant the emigrants had a difficult choice. They could make a dangerous river crossing here for a direct route to Ft. Boise or stay on the south side of the Snake and follow the river around the bend. About half made the decision to cross using the three islands in the Snake as stepping stones. It would not be easy.

"We lost 2 of our men, Ayres and Stringer. Ayres got into trouble with his mules in crossing the stream. Stringer, who was about thirty, went to his relief, and both were drowned in sight of their women folks. The bodies were never recovered."

Emigrant Samuel Hancock, 1852

Massacre on the Oregon Trail

"Two miles brought us to the scene of the late fight. Everything showed signs of a hard struggle. Six bodies lay by the road partly covered, by persons who had been here before. We got our spades & some of us stopped & gave them a decent burial. The ground is covered with blood. The tent poles and a great amount of half burnt feathers lay around. No wagons are left, I picked up a hat with two bullet holes in it and saturated with blood. I presume the owner received the ball in his head. A gun barrel was found and picked up. The stock had broken off and was badly bent. I imagine it was used, no doubt by some poor soul who was struggling desperately for life. After burying the dead I put up a notice to those behind to be on their guard and overlook the wagons. Every man now goes armed. Even the drivers carry their rifles in one hand and their whip in the other." Winfield Scott Ebey, August 24,1854

August 25, 1854

"I have learned more of the difficulty with the Indians. It seems the train stopped when Indians [some 60] came up apparently friendly. One of the Indians took off with a horse belonging to someone of the party. The owner also had two ponies. The Indians brought back the horse and grab his two ponies. Another man, who was a short distance from the wagons observing the movement of the Indians saw one of them point his gun at him, supposedly he intended to shoot him, he took out his revolver and shot the Indian down. The fight commenced in good earnest. Some of the men became frightened and I believe that but two of them had any experience in fighting. A young man by the name of Mulligan from the southern part of MO fought them to the last. It appears it was him that broke up his rifle fighting. It is thought that if all had stood up to them they would have driven the Indians off. Some of the men even crawled into the wagons, the Indians followed them up killing all - but the women & children. About this time, seven men of Mr. Yantes train coming back from the fort to look for the lost cow...and were in sight of the fight. The Indians then ran to the river about a mile off taking the women & children & some of the wagons, and hid in the bushes. The seven white men followed them and a fire was kept up for some time...the whites with revolvers & the Indians with HB muskets."

"Unfortunately the foremost man of the whites was shot dead and the party decided to retreat to the Fort for more help. Here was their error, had they charged the Indians in the bushes they might have saved the women & children but would probably lost some of their own number–they could hear the screams of captives in the bushes when they left. On their return it was found that the Indians had burned the wagons and had also burned up the children. Their bones were found on the spot, it is hoped they killed them before they committed them to the flames. But the men think otherwise and believe from the screams they heard that the children were burned alive, before their mother's eyes. The women [mother & daughter] were murdered and their bodies horribly violated. This is one of the most horrible, massacres of which I ever heard. A whole train of people killed in open day for plunder, and the Indians all escaping. Some 60 head of cattle and $2,000.00 in gold was carried off. I presume the Indians are now far enough away, and safe from pursuit."

In late August, word reached the outpost that the 20-member emigrant party of Alexander Ward was killed by a band of the Shoshoni Indians, along the part of the Oregon Trail that was close to Fort Boise and along the Boise River. Major Rains ordered Haller to take his command and aid any survivors and to punish the Indians responsible for this.

Because of discharges and desertions the two companies assigned to Fort Dalles only had a total of 56 soldiers. Haller took 26 of them with him to carry out his assignment. However, the citizens of the Dalles thought his command was too small and formed a company of 39 volunteers, under the command of Nathan Olney, who followed him and reported for duty. This mixed unit was also joined by a few warriors of the Nez Percés and Umatilla Indians that offered their services.

Upon arriving at the massacre sight they found 18 members of the party dead; only two boys had survived one of them being William Ward, the son of Alexander. William later explained what happened:

“My oldest brother, Robert, who was out guarding the stock, came running into camp and said the Indians had taken one of the horses. We hitched up as soon as possible and drove out on the road where it was more open. We had hardly reached the road when we were surrounded by Indians, about two hundred in all as we were afterwards told. They immediately attacked us but our men succeeded in keeping them off until nearly sundown when the men were all killed. Then they came to the wagons where the women and children were. My brother Newton [who also survived] and I attempted to escape to the brush but we were both shot down by arrows. I was shot through the left side and lung. The last thing I remember, they were riding their horses over me.”

Haller’s group looked around the area and discovered a grisly scene. The body of the Ward’s 17-year old daughter was discovered. Her body bore signs of their most brutal violence- a hot iron having been thrust into her person, doubtless while alive. Other bodies were also discovered like Mrs. White who had her head “beaten to a perfect jelly, her body stripped of its clothing, and bore marks of brutal treatment- she had been scalped.”

Mrs. Ward was found in the center of the camp and in front of her lay the crisped bodies of three of her children, who had doubtless, been burnt alive, and the mother forced to witness it. Mrs. Ward must have been severely tortured. Many scars were found upon her body, evidently made by a hot iron- her flesh cut in numerous places- and a tomahawk wound upon the right temple, which probably caused her death. Three more children who belonged to the party were not found.

Haller had the bodies buried and returned to Fort Dalles because the Indians had long since fled into the mountains and it was too late in the season to go find them. The soldiers did manage to kill some Indians and took a few others prisoner.

The following spring General John Wool, commanding the Department of the Pacific, ordered Haller to another expedition and to return to the Ward massacre site and to find and punish the Indians responsible; Haller had with him over 150 men, including Nathan Olney who was acting as an Indian Agent.

He reached the Fort Boise area on July 15 and the next day talks were held with around 200 hundred Indians that were gathered. During the talks it was determined that four of the participants of the Ward killing were among the present. Haller ordered their arrest and brought them before a military commission in which he reminded them that “the poor Indians cannot and should not be judged by the standards of the civilized and Christianized nations of the world, they were tried and found guilty of the killings”.

One of the Indians was shot while trying to escape but the other three were marched, on July 18, to the Ward site and the troops started to build gallows to carry out the sentence of the commission. The sentence was “read and interpreted to the Indians, who were placed in a wagon with ropes around their necks. The soldiers paraded at sundown, then the signal was given, the wagon drove from under the Indians, and they swung into eternity. The bodies were left handing until sunrise the next morning, and which time they were taken down and buried at the foot of the gallows.”

The bodies of the Ward party were also reburied because the wolves had dug them up during the winter. Once the burials were finished Haller, leaving the gallows standing, ordered an advanced and later established a supply depot on the Big Camash Prairie. From there he sent various parts of his command as far north as the headwaters of the Boise, Payette and Snake Rivers; to the east the Rocky Mountains and headwaters of the Missouri; to the south the Salmon Falls along the Snake River.

During this expedition, besides the killing of the four Indians, the command killed and hanged several more until the number of dead Indians equaled the number of dead whites. He also scattered the Shoshoni so that many of them fled towards the Humboldt River in California. The command returned home after covering a distance of around 1700 miles.

Contrary to cinematic depictions of Indian-white relations in the west, sustained attacks by Indians on emigrant wagon trains were rare. Although conflict did occur, historians note that “thievery and not murderous attack constituted the major threat posed by Indians.” In fact, mutual aid between Indians and overlanders was much more common than violent hostility.

Unfortunately, as the number of emigrants crossing the Oregon Trail increased over the course of the 1850s, Indian-white relations deteriorated. Estimates are that just over 360 emigrants were killed by Indians from 1840 to 1860, most of them during the 1850s. In comparison, he estimates that more than 425 Indians were killed by emigrants during the same period. The great majority of these violent conflicts occurred west of the Rockies, which was by far the most dangerous portion of the overland journey.

The first major massacre of emigrants by Indians occurred along the Snake River in 1854 by Shoshone Indians in what came to be known as the Ward Massacre. Six years later, the Snake River country would witness another attack, the Utter-Van Ornum Massacre.

The Utter-Van Ornum party left Wisconsin in May 1860, most heading for Oregon’s Willamette Valley. The wagon train—which consisted of eighteen men, five women, twenty-one children, twelve wagons, and one hundred head of livestock—arrived at the abandoned Fort Hall on August 21, 1860, encountering no major difficulties along the way. A company of U.S. Army dragoons had been stationed near the fort earlier that year to escort wagon trains through the Snake River country, but they escorted the Utter-Van Ornum party for only six days, purportedly because the commanding officer was upset with some members of the train.

About ten days after parting from the dragoon escort, the Utter-Van Ornum train was attacked by approximately one hundred Indians, probably a mixed group of Shoshone and Bannock, and perhaps accompanied by several white men. The attack and its aftermath are described in detail in the accompanying newspaper article.

Eleven emigrants were killed during the first two days, after which the survivors abandoned their wagons and fled, splitting into several groups. The Van Ornums and three other emigrants were later killed in mid-October near present-day Huntington. Another group stayed along the Owyhee River, where they slowly starved. Five of the emigrants, four of them children, died while waiting for rescue, and the survivors were forced to eat the remains. They were finally rescued by the U.S. Army forty-five days after the initial attack. Of the original forty-four members of the Utter-Van Ornum party, only sixteen survived, including one of the Van Ornum children who was rescued from the Shoshone two years later.

"Two miles brought us to the scene of the late fight. Everything showed signs of a hard struggle. Six bodies lay by the road partly covered, by persons who had been here before. We got our spades & some of us stopped & gave them a decent burial. The ground is covered with blood. The tent poles and a great amount of half burnt feathers lay around. No wagons are left, I picked up a hat with two bullet holes in it and saturated with blood. I presume the owner received the ball in his head. A gun barrel was found and picked up. The stock had broken off and was badly bent. I imagine it was used, no doubt by some poor soul who was struggling desperately for life. After burying the dead I put up a notice to those behind to be on their guard and overlook the wagons. Every man now goes armed. Even the drivers carry their rifles in one hand and their whip in the other." Winfield Scott Ebey, August 24,1854

August 25, 1854

"I have learned more of the difficulty with the Indians. It seems the train stopped when Indians [some 60] came up apparently friendly. One of the Indians took off with a horse belonging to someone of the party. The owner also had two ponies. The Indians brought back the horse and grab his two ponies. Another man, who was a short distance from the wagons observing the movement of the Indians saw one of them point his gun at him, supposedly he intended to shoot him, he took out his revolver and shot the Indian down. The fight commenced in good earnest. Some of the men became frightened and I believe that but two of them had any experience in fighting. A young man by the name of Mulligan from the southern part of MO fought them to the last. It appears it was him that broke up his rifle fighting. It is thought that if all had stood up to them they would have driven the Indians off. Some of the men even crawled into the wagons, the Indians followed them up killing all - but the women & children. About this time, seven men of Mr. Yantes train coming back from the fort to look for the lost cow...and were in sight of the fight. The Indians then ran to the river about a mile off taking the women & children & some of the wagons, and hid in the bushes. The seven white men followed them and a fire was kept up for some time...the whites with revolvers & the Indians with HB muskets."

"Unfortunately the foremost man of the whites was shot dead and the party decided to retreat to the Fort for more help. Here was their error, had they charged the Indians in the bushes they might have saved the women & children but would probably lost some of their own number–they could hear the screams of captives in the bushes when they left. On their return it was found that the Indians had burned the wagons and had also burned up the children. Their bones were found on the spot, it is hoped they killed them before they committed them to the flames. But the men think otherwise and believe from the screams they heard that the children were burned alive, before their mother's eyes. The women [mother & daughter] were murdered and their bodies horribly violated. This is one of the most horrible, massacres of which I ever heard. A whole train of people killed in open day for plunder, and the Indians all escaping. Some 60 head of cattle and $2,000.00 in gold was carried off. I presume the Indians are now far enough away, and safe from pursuit."

In late August, word reached the outpost that the 20-member emigrant party of Alexander Ward was killed by a band of the Shoshoni Indians, along the part of the Oregon Trail that was close to Fort Boise and along the Boise River. Major Rains ordered Haller to take his command and aid any survivors and to punish the Indians responsible for this.

Because of discharges and desertions the two companies assigned to Fort Dalles only had a total of 56 soldiers. Haller took 26 of them with him to carry out his assignment. However, the citizens of the Dalles thought his command was too small and formed a company of 39 volunteers, under the command of Nathan Olney, who followed him and reported for duty. This mixed unit was also joined by a few warriors of the Nez Percés and Umatilla Indians that offered their services.

Upon arriving at the massacre sight they found 18 members of the party dead; only two boys had survived one of them being William Ward, the son of Alexander. William later explained what happened:

“My oldest brother, Robert, who was out guarding the stock, came running into camp and said the Indians had taken one of the horses. We hitched up as soon as possible and drove out on the road where it was more open. We had hardly reached the road when we were surrounded by Indians, about two hundred in all as we were afterwards told. They immediately attacked us but our men succeeded in keeping them off until nearly sundown when the men were all killed. Then they came to the wagons where the women and children were. My brother Newton [who also survived] and I attempted to escape to the brush but we were both shot down by arrows. I was shot through the left side and lung. The last thing I remember, they were riding their horses over me.”

Haller’s group looked around the area and discovered a grisly scene. The body of the Ward’s 17-year old daughter was discovered. Her body bore signs of their most brutal violence- a hot iron having been thrust into her person, doubtless while alive. Other bodies were also discovered like Mrs. White who had her head “beaten to a perfect jelly, her body stripped of its clothing, and bore marks of brutal treatment- she had been scalped.”

Mrs. Ward was found in the center of the camp and in front of her lay the crisped bodies of three of her children, who had doubtless, been burnt alive, and the mother forced to witness it. Mrs. Ward must have been severely tortured. Many scars were found upon her body, evidently made by a hot iron- her flesh cut in numerous places- and a tomahawk wound upon the right temple, which probably caused her death. Three more children who belonged to the party were not found.

Haller had the bodies buried and returned to Fort Dalles because the Indians had long since fled into the mountains and it was too late in the season to go find them. The soldiers did manage to kill some Indians and took a few others prisoner.

The following spring General John Wool, commanding the Department of the Pacific, ordered Haller to another expedition and to return to the Ward massacre site and to find and punish the Indians responsible; Haller had with him over 150 men, including Nathan Olney who was acting as an Indian Agent.

He reached the Fort Boise area on July 15 and the next day talks were held with around 200 hundred Indians that were gathered. During the talks it was determined that four of the participants of the Ward killing were among the present. Haller ordered their arrest and brought them before a military commission in which he reminded them that “the poor Indians cannot and should not be judged by the standards of the civilized and Christianized nations of the world, they were tried and found guilty of the killings”.

One of the Indians was shot while trying to escape but the other three were marched, on July 18, to the Ward site and the troops started to build gallows to carry out the sentence of the commission. The sentence was “read and interpreted to the Indians, who were placed in a wagon with ropes around their necks. The soldiers paraded at sundown, then the signal was given, the wagon drove from under the Indians, and they swung into eternity. The bodies were left handing until sunrise the next morning, and which time they were taken down and buried at the foot of the gallows.”

The bodies of the Ward party were also reburied because the wolves had dug them up during the winter. Once the burials were finished Haller, leaving the gallows standing, ordered an advanced and later established a supply depot on the Big Camash Prairie. From there he sent various parts of his command as far north as the headwaters of the Boise, Payette and Snake Rivers; to the east the Rocky Mountains and headwaters of the Missouri; to the south the Salmon Falls along the Snake River.

During this expedition, besides the killing of the four Indians, the command killed and hanged several more until the number of dead Indians equaled the number of dead whites. He also scattered the Shoshoni so that many of them fled towards the Humboldt River in California. The command returned home after covering a distance of around 1700 miles.

Contrary to cinematic depictions of Indian-white relations in the west, sustained attacks by Indians on emigrant wagon trains were rare. Although conflict did occur, historians note that “thievery and not murderous attack constituted the major threat posed by Indians.” In fact, mutual aid between Indians and overlanders was much more common than violent hostility.

Unfortunately, as the number of emigrants crossing the Oregon Trail increased over the course of the 1850s, Indian-white relations deteriorated. Estimates are that just over 360 emigrants were killed by Indians from 1840 to 1860, most of them during the 1850s. In comparison, he estimates that more than 425 Indians were killed by emigrants during the same period. The great majority of these violent conflicts occurred west of the Rockies, which was by far the most dangerous portion of the overland journey.

The first major massacre of emigrants by Indians occurred along the Snake River in 1854 by Shoshone Indians in what came to be known as the Ward Massacre. Six years later, the Snake River country would witness another attack, the Utter-Van Ornum Massacre.

The Utter-Van Ornum party left Wisconsin in May 1860, most heading for Oregon’s Willamette Valley. The wagon train—which consisted of eighteen men, five women, twenty-one children, twelve wagons, and one hundred head of livestock—arrived at the abandoned Fort Hall on August 21, 1860, encountering no major difficulties along the way. A company of U.S. Army dragoons had been stationed near the fort earlier that year to escort wagon trains through the Snake River country, but they escorted the Utter-Van Ornum party for only six days, purportedly because the commanding officer was upset with some members of the train.

About ten days after parting from the dragoon escort, the Utter-Van Ornum train was attacked by approximately one hundred Indians, probably a mixed group of Shoshone and Bannock, and perhaps accompanied by several white men. The attack and its aftermath are described in detail in the accompanying newspaper article.

Eleven emigrants were killed during the first two days, after which the survivors abandoned their wagons and fled, splitting into several groups. The Van Ornums and three other emigrants were later killed in mid-October near present-day Huntington. Another group stayed along the Owyhee River, where they slowly starved. Five of the emigrants, four of them children, died while waiting for rescue, and the survivors were forced to eat the remains. They were finally rescued by the U.S. Army forty-five days after the initial attack. Of the original forty-four members of the Utter-Van Ornum party, only sixteen survived, including one of the Van Ornum children who was rescued from the Shoshone two years later.

News Article, Snake River Massacre Account by One of the Survivors

Catalog Number: Oregon Argus, November 24, 1860

Date: November 24, 1860

The Oregon Argus

OREGON CITY, OREGON, NOVEMBER 24, 1860

The Snake River Massacre – Account by one of its Survivors

“After we had been in camp on the Owyhee about three weeks, the Van Norman family, consisting of himself, wife, fives children, and Samuel Gleason, Chas. Utter, Henry Utter, concluded to leave, and travel on as well as they could. They got together what provisions they could, and started. They refused to allow Miss Trimble to go with them. That is the last we heard of the Van Norman Family, till Capt. Dent’s party came. They found the Van Norman family on the Burnt River all murdered, apparently but a few days previous. Capt. Dent found all the bodies excepting those of four children, three girls and one boy, the eldest girl was about 16. It is supposed they were taken prisoners and probably are yet alive.”

“The survivors were nothing but skin and bone, and the children so weak they would tumble down when they tried to run. Their fingers were like birds' claws; eyes hollow-looking; cheeks sunken; they seemed to be half out of their senses; they would sit there and quarrel about who had the biggest piece of meat, and fuss about any little foolish thing. Sometimes they would be in fine spirits—talk about good old times, assistance coming, of their plans and prospects when they got into the settlements, &c.; then they would realize their true situation, and commence crying. When Capt. Dent came into the valley where the camp was, the first one he saw was Miss Trimble, who had wandered off a few hundred yards, gathering something to eat. (She is the young lady who picked up an infant at the time of the massacre, and carried it along till it died; she also defended the wagon some time with an ax in hand.) Capt. Dent spoke to her, and asked if she was hungry. 'No, sir, not much.' 'Are you not afraid of the Indians.' 'No, sir'—and seemed to take every thing very coolly. She seemed to be half out of her mind. As soon as these poor, starved people saw the soldiers coming, they ran out and fell on the ground, crying that they were starving, and begging for something to eat. Those that were stout enough to ride were put on mules, and the others were carried in litters between two mules.”

At The Dalles, Oregon

The Columbia River rumbled through a narrow chasm. It was here that a Methodist mission was established in 1838. History does not tell us how many were at the tiny outpost, but The Dalles did become a critical stop for the emigrants. It was here that the trail ruts came to a complete stop--blocked by the Cascade Mountains. Unfortunately, the Willamette Valley, the emigrant's destination--was still 100 miles further on. In the first years of the Oregon Trail, there was only one solution--float the wagons down the Columbia River.

Emigrant diaries:

"The appearance of the river here changes--and from being a rapid, shallow and narrow stream, it becomes a wide, deep and still one, in some places more than a mile wide and too deep to be sounded. The banks are precipitous and rocky, and several hundred feet high in some places. Passed down to an immense pile of loose rocks across the stream, over which the water runs with great rapidity for six miles."

Because of the swirling rapids, the trip down the Columbia was especially treacherous.

So close to their destinations after months of traveling, tragedy was still a very real concern.

Emigrant diaries:

"One of our boats, containing six persons, was caught in one of those terrible whirlpools and upset. My son, ten-years-old, my brother Jesse's son Edward, same age, were lost. It was a painful scene beyond description. We dared not go to their assistance without exposing the occupants of the other boat to certain destruction. The bodies of the drowned were never recovered."

Many emigrants soon realized they could not navigate the hazardous river themselves, so they hired experts--Native Americans.

Emigrant diaries:

"It requires the most dexterous management, which these wild navigators are masters of, to pass the dreadful chasm in safety. A single stroke amiss, would be inevitable destruction."

Even with Native American help, floating the Columbia was risky. Commercial ferrymen also set up shop, but their prices were outlandishly high. Even if an emigrant was willing to pay the steep fee, there were not enough ferry boats available to handle the flood of wagons rolling in. So here at The Dalles they waited for days--or weeks. As a result, a city was born.

Proudly powered by Weebly