Field of Battle at North Inch, Perth

1396 - “A selcouth thing”

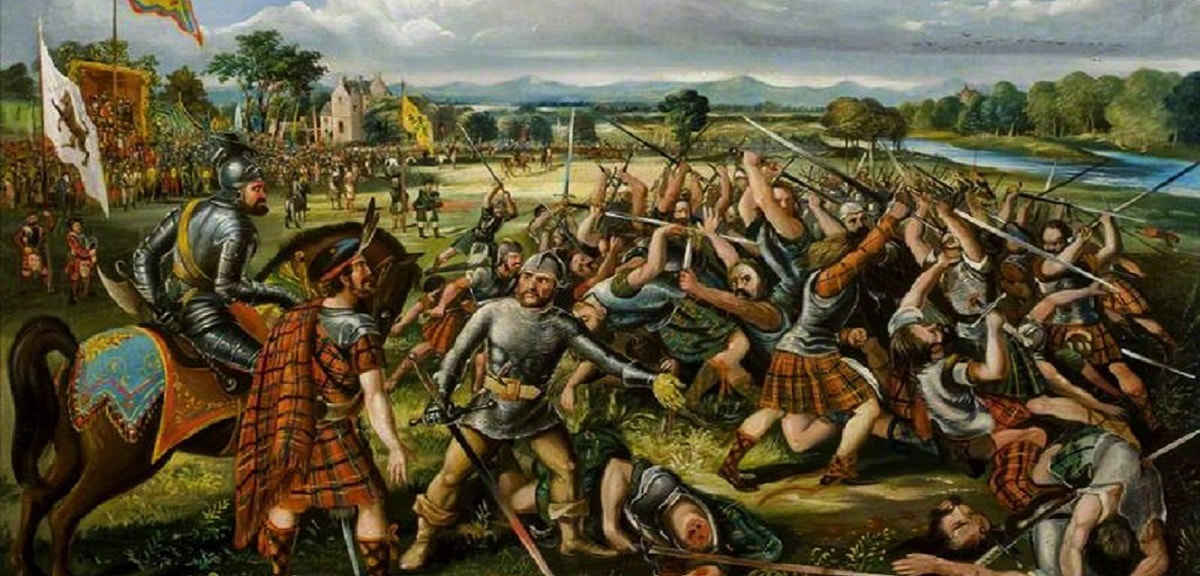

“A selcouth thing” (an amazing thing) was what one witness called it. The Battle of the Clans (also known as the Battle of the North Inch) was a duel between two sides of thirty highland warriors in which quarter was neither given nor asked. Intended to resolve a raging feud that threatened Scotland’s stability in 1396, the contest was a shocking spectacle, notable even in an age that concealed its brutality behind a veil of chivalry. Taking place in a makeshift arena before the King, his court, foreign dignitaries and hundreds of spectators, the Battle of the Clans was a reversion to the gladiatorial games of pagan Rome. This trial by combat was also a reflection of the tensions between the culture of the Lowland Scots and their Anglo-Norman rulers and the tribalism of the Celtic Highlanders. Those tensions would remain unresolved until the final clash of cultures on the field of Culloden in 1745.

A battle that would have been almost comic if not for brutality and the very real loss of life involved. The absence of such a notable event from most official records suggests that the entire exercise was regarded by the authorities as a somewhat shameful failure, best not to be mentioned again.

The Dispute

The fourteenth century Scottish highland region was still an isolated and undeveloped district of great forests, deep cold lakes and rocky peaks uncrossed by any road. Towns were few, with most of the population scattered through the glens (valleys), where they pursued a pastoral life, occasionally enlivened by raids against their neighbours and disputes over land. What went on in the highlands was still largely a mystery to the outside world, including Scotland’s king, Robert III Stewart.

The combat at Perth was likely the result of a feud that erupted around 1333 between Clan Cameron and Clan Chattan, two powerful highland confederacies. Most major disputes in the highlands were over land, and this one was no different, involving a claim for restoration of MacIntosh (or MacKintosh) lands in Lochaber temporarily held by the Camerons. The MacIntosh chief, leader of the Clan Chattan confederacy, attacked and defeated the Camerons at Drumlui, and from there, ... the feud was on. As the fighting took its toll, each confederation began to call on its complex network of allies for armed support, threatening to plunge the entire highland region into a cauldron of unstoppable violence.

The fight at Drumlui was followed by the Battle of Invernahavon, which took place in 1386. This fierce struggle pitted the MacPhersons, Davidsons and MacIntoshes (the main elements of Clan Chattan) against some four hundred warriors of the Clan Cameron, returning home from a raid on Clan Chattan lands in Badenoch. It was no cruel insult that launched this feud, or even the usual incidents of rape, pillage or plunder. The uproar was about something as mundane as unpaid rent. The resulting battle called The Battle of Invernahoven and that started a feud between these two clans ten years prior.

With this clash, the highlanders had passed from traditional nuisance to serious threat to the established order. Indeed, there was growing criticism of the king’s failure to maintain law and order in the kingdom. In those days there was no law in Scotland, but the strong opposed the weak and the whole kingdom was one den of thieves. Homicides, robberies, fire-raisings and other misdeeds remained unpunished, and justice seemed banished beyond the king’s bounds.

Everyone involved had became weary of the dispute; not weary enough to end it, of course, but weary enough to ask King Robert III to intervene. King Robert III, being the sort of sovereign who made sure his own interests ranked first in any dispute he settled, came up with an ingenious solution. Each of the two clans, Chattan and MacPherson, were to send 30 of their best warriors into a battle-to-the-death. The place was a beautiful, level field (an “inch” in Gaelic) called North Inch in Perth. This move made King Robert III the first and last king in Scots history to have a battle-to-the-death staged for his amusement.

North Inch of Perth

The “North Inch” was an area of low-lying land beside the River Tay, just outside the town walls and home to a monastery of Dominican priests known as “The Black Friars.” The choice of Perth for this unusual mass duel was likely due to the favor shown the town by the king as a residence. At this time, as in many mediaeval societies, the Scottish king and court had no permanent home, preferring instead to pass from place to place, allowing the king to “show the flag” when and where convenient or necessary. Robert III enjoyed his stays at the Black Friars’ monastery at Perth best, and the marshy ground of the North Inch was a natural choice for the contest, having already been used for a number of individual trials-by-combat.

Historians, however, have theorized there may have been more than amusement in Robert’s planning. The trouble-someness of the two clans would be greatly reduced. He is believed to have thought, if their main warriors were permanently removed from action.

Most of historic references indicate those who took part in this combat were the MacPhersons and Clan Chattan, of whom some of the Davidsons of Invernahaven were a part.

The conflict was set for the Monday before Michaelmas, October 23. As to weapons, some historians say only the broadsword was used, but others say that bows, battle-axes and daggers were also permitted. This view would be supported by the following account of the event.

Royal carpenters had been busy building a grandstand from which the king, his queen, Annabella Drummond, Scots nobles and a number of foreign dignitaries could view the proceedings. Barriers were constructed around three sides of the intended battleground, the River Tay forming the fourth side. Viewing stands were erected for the King, his court, and noble visitors, some of whom came all the way from France for the spectacle. There was no doubt a large turnout from Perth, and hundreds of spectators and vendors must have flocked in from the hinterland to take in this once-in-a-lifetime event. The funds for erecting the grandstands were taken from the King’s customs account at Perth. The exchequer rolls record the expenditure of £ 14:2:11 “for timber, iron and making of lists (enclosures) for 60 persons fighting in the Inch of Perth”.

On the selected day, the king and queen led a procession to the grandstand. Following them were the nobility and honored foreign guests. With the grandstands jammed with the upper classes, the commoners packed the sidelines behind barriers designed to keep them off the field of battle.

A battle that would have been almost comic if not for brutality and the very real loss of life involved. The absence of such a notable event from most official records suggests that the entire exercise was regarded by the authorities as a somewhat shameful failure, best not to be mentioned again.

The Dispute

The fourteenth century Scottish highland region was still an isolated and undeveloped district of great forests, deep cold lakes and rocky peaks uncrossed by any road. Towns were few, with most of the population scattered through the glens (valleys), where they pursued a pastoral life, occasionally enlivened by raids against their neighbours and disputes over land. What went on in the highlands was still largely a mystery to the outside world, including Scotland’s king, Robert III Stewart.

The combat at Perth was likely the result of a feud that erupted around 1333 between Clan Cameron and Clan Chattan, two powerful highland confederacies. Most major disputes in the highlands were over land, and this one was no different, involving a claim for restoration of MacIntosh (or MacKintosh) lands in Lochaber temporarily held by the Camerons. The MacIntosh chief, leader of the Clan Chattan confederacy, attacked and defeated the Camerons at Drumlui, and from there, ... the feud was on. As the fighting took its toll, each confederation began to call on its complex network of allies for armed support, threatening to plunge the entire highland region into a cauldron of unstoppable violence.

The fight at Drumlui was followed by the Battle of Invernahavon, which took place in 1386. This fierce struggle pitted the MacPhersons, Davidsons and MacIntoshes (the main elements of Clan Chattan) against some four hundred warriors of the Clan Cameron, returning home from a raid on Clan Chattan lands in Badenoch. It was no cruel insult that launched this feud, or even the usual incidents of rape, pillage or plunder. The uproar was about something as mundane as unpaid rent. The resulting battle called The Battle of Invernahoven and that started a feud between these two clans ten years prior.

With this clash, the highlanders had passed from traditional nuisance to serious threat to the established order. Indeed, there was growing criticism of the king’s failure to maintain law and order in the kingdom. In those days there was no law in Scotland, but the strong opposed the weak and the whole kingdom was one den of thieves. Homicides, robberies, fire-raisings and other misdeeds remained unpunished, and justice seemed banished beyond the king’s bounds.

Everyone involved had became weary of the dispute; not weary enough to end it, of course, but weary enough to ask King Robert III to intervene. King Robert III, being the sort of sovereign who made sure his own interests ranked first in any dispute he settled, came up with an ingenious solution. Each of the two clans, Chattan and MacPherson, were to send 30 of their best warriors into a battle-to-the-death. The place was a beautiful, level field (an “inch” in Gaelic) called North Inch in Perth. This move made King Robert III the first and last king in Scots history to have a battle-to-the-death staged for his amusement.

North Inch of Perth

The “North Inch” was an area of low-lying land beside the River Tay, just outside the town walls and home to a monastery of Dominican priests known as “The Black Friars.” The choice of Perth for this unusual mass duel was likely due to the favor shown the town by the king as a residence. At this time, as in many mediaeval societies, the Scottish king and court had no permanent home, preferring instead to pass from place to place, allowing the king to “show the flag” when and where convenient or necessary. Robert III enjoyed his stays at the Black Friars’ monastery at Perth best, and the marshy ground of the North Inch was a natural choice for the contest, having already been used for a number of individual trials-by-combat.

Historians, however, have theorized there may have been more than amusement in Robert’s planning. The trouble-someness of the two clans would be greatly reduced. He is believed to have thought, if their main warriors were permanently removed from action.

Most of historic references indicate those who took part in this combat were the MacPhersons and Clan Chattan, of whom some of the Davidsons of Invernahaven were a part.

The conflict was set for the Monday before Michaelmas, October 23. As to weapons, some historians say only the broadsword was used, but others say that bows, battle-axes and daggers were also permitted. This view would be supported by the following account of the event.

Royal carpenters had been busy building a grandstand from which the king, his queen, Annabella Drummond, Scots nobles and a number of foreign dignitaries could view the proceedings. Barriers were constructed around three sides of the intended battleground, the River Tay forming the fourth side. Viewing stands were erected for the King, his court, and noble visitors, some of whom came all the way from France for the spectacle. There was no doubt a large turnout from Perth, and hundreds of spectators and vendors must have flocked in from the hinterland to take in this once-in-a-lifetime event. The funds for erecting the grandstands were taken from the King’s customs account at Perth. The exchequer rolls record the expenditure of £ 14:2:11 “for timber, iron and making of lists (enclosures) for 60 persons fighting in the Inch of Perth”.

On the selected day, the king and queen led a procession to the grandstand. Following them were the nobility and honored foreign guests. With the grandstands jammed with the upper classes, the commoners packed the sidelines behind barriers designed to keep them off the field of battle.

The Battle

The combatants – the MacPhersons and the clan Chattan – marched, each procession was preceded by their pipes and drummers and armed with their swords, targes, bows and arrows, knives and battle-axes. The Dominican priests would have insisted on conducting Mass prior to the bloodletting, al the while, each side would glare, sizing up their opponents. When the warriors were mustered on the field after attending mass it was discovered that Clan Chattan was one man short.

The missing highlander was variously described as having missed the fight as the result of a hangover or an over-long dalliance with one of the young ladies of Perth. However, with none of the fighters on the opposing side willing to relinquish their role in order to even up the sides, the combat was suddenly in danger of being abandoned.

Traditions record that a local smith with no interest in the fight stepped up and volunteered to join the combat in place of the missing warrior, in return for an immediate sum of money and a guarantee he would be maintained for life in the unlikely event of his survival. The bandy-legged smith was described as “small in stature, but fierce.” The replacement was named Henry Wynd,

With the fight on once more the fighters, following highland tradition, would have stripped to their saffron-coloured undershirts, tying the long garment between their legs before going into battle. Chain mail was the usual costume of professional warriors in the Highlands at this time, but protection of the combatants did not figure into the scheme of the contest’s organizers. Before highlanders met in battle it was customary for a bard from each side to recite a poem intended to incite the warriors and remind them of their duty to their clan. Following this the warriors would have hurled insults and brandished their weapons while awaiting the sound of the trumpet that would launch the fray.

"The trumpets of the king sounded a charge, the bagpipes blew up their screaming and maddening notes, and the combatants, starting forward in regular order, and increasing their pace till they came to a smart run, met together in the centre of the ground, as a furious torrent encounters an advancing tide. For an instant or two the front lines, hewing at each other with their long swords, seemed engaged in a succession of single combats; but the second and third ranks soon came up on either side, actuated alike by the eagerness of hatred and the thirst of honor, pressed through the intervals, and rendered the scene a tumultuous chaos, over which the huge swords rose and sunk, some still glittering, others streaming with blood, appearing, from the wild rapidity with which they were swayed, rather to be put in motion by some complicated machinery, than to be wielded by human hands."

We are told that the fighters could carry only bow, axe, knife and sword, and that armour and shields were prohibited. The bows would have been used first, with probably only a small number of arrows allowed on each side before the warriors closed in. One account holds that the bows were actually crossbows, and that only three arrows were allotted to each. In an enclosure at short distance any shot, whether from bow or crossbow, would likely have been lethal in the hands of experienced bowmen. Despite some later accounts that mention its use in the fight, the two-handed claymore or “great sword” was not introduced to the highlands until the 15th century. The small ground chosen for the combat would have left little opportunity to employ any type of tactics, and the warriors likely paired off in single combat at first, in the highland tradition. As men fell on each side, some fighters may have found themselves faced with two or three opponents. In this case death was almost certain, especially as the fighters were without protection. The struggle must have been ferocious at times; according to the "The Scotichronicon" in the 15th Century chronicler, Walter Bower’s account, it was “like butchers killing cattle in a slaughter-house.”

From time to time it would have been necessary for the combatants to break off and rest from their exertions, and to attempt to staunch the flow of blood from the worst of their wounds. On the trumpet signal, the fight would resume on fresh ground, unencumbered by the mutilated bodies of their dying comrades. A story from the folklore of the MacPherson clan (and repeated by Sir Walter Scott in The Fair Maid of Perth) describes the pipers of the respective clans becoming enraged by the slaughter, dropping their pipes to go at each other with knives. Having slain his opponent, the mortally wounded Clan Chattan piper is said to have picked up his pipes to play the clan anthem with his dying breath. The clash of pipers appears, unfortunately, to be yet another late addition to the saga, making its first appearance on paper in the early 19th century. The oral tradition may be much older, but almost certainly does not go back before the 17th century.

After several hours of bloodletting, there remained only one of the MacPhersons left opposing the Clan Chattan. Alone, one against eleven heavily wounded representatives of the Clan of the Cat. Rightly judging his chance of survival as nil, the warrior tossed his sword away and struck out across the River Tay. If he indeed survived the swim (and he must have been badly wounded himself), the warrior was never heard from again, though Scott recorded a folk-tale in which the man was so poorly received on his return to his kin in the highlands that he killed himself.

The combatants – the MacPhersons and the clan Chattan – marched, each procession was preceded by their pipes and drummers and armed with their swords, targes, bows and arrows, knives and battle-axes. The Dominican priests would have insisted on conducting Mass prior to the bloodletting, al the while, each side would glare, sizing up their opponents. When the warriors were mustered on the field after attending mass it was discovered that Clan Chattan was one man short.

The missing highlander was variously described as having missed the fight as the result of a hangover or an over-long dalliance with one of the young ladies of Perth. However, with none of the fighters on the opposing side willing to relinquish their role in order to even up the sides, the combat was suddenly in danger of being abandoned.

Traditions record that a local smith with no interest in the fight stepped up and volunteered to join the combat in place of the missing warrior, in return for an immediate sum of money and a guarantee he would be maintained for life in the unlikely event of his survival. The bandy-legged smith was described as “small in stature, but fierce.” The replacement was named Henry Wynd,

With the fight on once more the fighters, following highland tradition, would have stripped to their saffron-coloured undershirts, tying the long garment between their legs before going into battle. Chain mail was the usual costume of professional warriors in the Highlands at this time, but protection of the combatants did not figure into the scheme of the contest’s organizers. Before highlanders met in battle it was customary for a bard from each side to recite a poem intended to incite the warriors and remind them of their duty to their clan. Following this the warriors would have hurled insults and brandished their weapons while awaiting the sound of the trumpet that would launch the fray.

"The trumpets of the king sounded a charge, the bagpipes blew up their screaming and maddening notes, and the combatants, starting forward in regular order, and increasing their pace till they came to a smart run, met together in the centre of the ground, as a furious torrent encounters an advancing tide. For an instant or two the front lines, hewing at each other with their long swords, seemed engaged in a succession of single combats; but the second and third ranks soon came up on either side, actuated alike by the eagerness of hatred and the thirst of honor, pressed through the intervals, and rendered the scene a tumultuous chaos, over which the huge swords rose and sunk, some still glittering, others streaming with blood, appearing, from the wild rapidity with which they were swayed, rather to be put in motion by some complicated machinery, than to be wielded by human hands."

We are told that the fighters could carry only bow, axe, knife and sword, and that armour and shields were prohibited. The bows would have been used first, with probably only a small number of arrows allowed on each side before the warriors closed in. One account holds that the bows were actually crossbows, and that only three arrows were allotted to each. In an enclosure at short distance any shot, whether from bow or crossbow, would likely have been lethal in the hands of experienced bowmen. Despite some later accounts that mention its use in the fight, the two-handed claymore or “great sword” was not introduced to the highlands until the 15th century. The small ground chosen for the combat would have left little opportunity to employ any type of tactics, and the warriors likely paired off in single combat at first, in the highland tradition. As men fell on each side, some fighters may have found themselves faced with two or three opponents. In this case death was almost certain, especially as the fighters were without protection. The struggle must have been ferocious at times; according to the "The Scotichronicon" in the 15th Century chronicler, Walter Bower’s account, it was “like butchers killing cattle in a slaughter-house.”

From time to time it would have been necessary for the combatants to break off and rest from their exertions, and to attempt to staunch the flow of blood from the worst of their wounds. On the trumpet signal, the fight would resume on fresh ground, unencumbered by the mutilated bodies of their dying comrades. A story from the folklore of the MacPherson clan (and repeated by Sir Walter Scott in The Fair Maid of Perth) describes the pipers of the respective clans becoming enraged by the slaughter, dropping their pipes to go at each other with knives. Having slain his opponent, the mortally wounded Clan Chattan piper is said to have picked up his pipes to play the clan anthem with his dying breath. The clash of pipers appears, unfortunately, to be yet another late addition to the saga, making its first appearance on paper in the early 19th century. The oral tradition may be much older, but almost certainly does not go back before the 17th century.

After several hours of bloodletting, there remained only one of the MacPhersons left opposing the Clan Chattan. Alone, one against eleven heavily wounded representatives of the Clan of the Cat. Rightly judging his chance of survival as nil, the warrior tossed his sword away and struck out across the River Tay. If he indeed survived the swim (and he must have been badly wounded himself), the warrior was never heard from again, though Scott recorded a folk-tale in which the man was so poorly received on his return to his kin in the highlands that he killed himself.

The smith of Perth was another matter, however. Having played a decisive role in the fight on the side of Clan Chattan, the smith was afterwards asked if he even understood for what he had fought so relentlessly. The smith was said to have replied that he had “fought for his own hand,” a phrase that passed into Scottish lore. Clan Chattan appears to have honoured its promise to the smith, who is said to have left for the North with his fellow survivors, settling in Strahavon. His descendants became known as Sliochd an Gobh Cruim (“the race of the crooked smith,” referring to his bandy-legs), and may still be found in the area as a sept of Clan Chattan, bearing the names of Smith or its Gaelic equivalent, Gow.

The Leaders

The participation of Clan Chattan in the duel is undisputed, but there has been considerable controversy over their opponents. Many have suggested that the battle was actually between two branches of Clan Chattan vying for prominence. Traditions held by the MacPhersons and the Davidsons (both Clan Chattan) insist that the Camerons had no part in the contest. Arguing against this claim is the fact that in the late 14th century, the constituent families of Clan Chattan were neither large nor powerful on their own, and a feud between two individual groups within the confederation would hardly have been of enough seriousness as to threaten the stability of the whole nation, the given reason for the duel. The combative Clan Cameron confederation and their long-standing quarrel with Clan Chattan makes them a much more likely opponent in the contest at Perth. There is also some evidence that Clan Cameron had not yet adopted that name in the 14th century, so they may well have been known as Clan ‘Ha’ at the time. It is nearly impossible to say with certainty exactly who were the opponents at the North Inch, but a group of warriors from the leading clans of the Chattan confederacy versus a group of Clan Cameron warriors seems most likely, but far from definite, with strong MacPherson traditions in need of account. Clan Davidson maintains that it formed one of the two sides in what it interprets as a battle for the Clan Chattan leadership, and in 1996 held a celebration in Perth of the 600th anniversary of the Battle of the North Inch, the clan piper playing a new piece commissioned for the occasion.

The Leaders

The participation of Clan Chattan in the duel is undisputed, but there has been considerable controversy over their opponents. Many have suggested that the battle was actually between two branches of Clan Chattan vying for prominence. Traditions held by the MacPhersons and the Davidsons (both Clan Chattan) insist that the Camerons had no part in the contest. Arguing against this claim is the fact that in the late 14th century, the constituent families of Clan Chattan were neither large nor powerful on their own, and a feud between two individual groups within the confederation would hardly have been of enough seriousness as to threaten the stability of the whole nation, the given reason for the duel. The combative Clan Cameron confederation and their long-standing quarrel with Clan Chattan makes them a much more likely opponent in the contest at Perth. There is also some evidence that Clan Cameron had not yet adopted that name in the 14th century, so they may well have been known as Clan ‘Ha’ at the time. It is nearly impossible to say with certainty exactly who were the opponents at the North Inch, but a group of warriors from the leading clans of the Chattan confederacy versus a group of Clan Cameron warriors seems most likely, but far from definite, with strong MacPherson traditions in need of account. Clan Davidson maintains that it formed one of the two sides in what it interprets as a battle for the Clan Chattan leadership, and in 1996 held a celebration in Perth of the 600th anniversary of the Battle of the North Inch, the clan piper playing a new piece commissioned for the occasion.

The Aftermath

The mass duel at Perth had little political legacy. Though the Scottish court may have been relieved to remove so many troublesome warriors from the scene in one day, both highland confederacies were large enough to withstand the loss. Neither side would have taken the result of the combat at Perth as a decision against them in their feud. The Norman rules of law that lay behind this judicial contest of arms were unknown in the highlands. There the code of blood revenge would have dictated further rounds of bloodletting in return for the deeds of that September afternoon. If the clans involved were indeed the Chattan and the Camerons, it is known that they were at each other’s throats once again early in the 15th century. There are records of a particularly ruthless attack on Palm Sunday, 1429, in which the Clan Chattan set fire to a church where a sept of Clan Cameron was gathered, killing most of those gathered within. The contenders for leadership of the Clan Chattan were not above fighting each other, as at the Battle of Glenlivet in 1594. The leadership dispute was eventually settled in court near the end of the 17th century, legal proceedings having replaced “battles to the death” by this time. The fact that the contest at Perth was largely ignored by official records after its conclusion and was never repeated would seem to confirm the ineffectiveness of this form of trial by combat as a means of dispute resolution amongst the highlanders.

Legends and Relics

Walter Scott’s 1828 account of the battle at North Inch features a remarkable display of devotion as the foster father and eight foster brothers of Eachin (‘Hector’, the son of the Clan Qwhele chief) sacrifice themselves to save the young man from the attacks of the Chattan warriors. As each falls in turn another foster-brother replaces the last with the cry “Another for Hector!” Scott’s version of the North Inch battle was never intended to be an historical account. The author always preferred vague and often disputed historical traditions as the basis of his stories.

In 1745 the Battle of Culloden brought an end to the Jacobite rebellion and dreams of a Stewart restoration in Britain. The Highland charge, which had triumphed so many times against English arms in the past, proved unequal that day to the disciplined fire and bayonet drill of the Duke of Cumberland’s army. Leading the Jacobite charge were the MacIntoshes of Clan Chattan, who left nearly their entire fighting strength in a mass graves on the battlefield. The Camerons were right behind them, their shot and bayonet-mangled bodies left intermingled with those of their ancient rivals. After the tragic finale to the “Rising of ’45,” the North Inch of Perth became home to a camp of Hessian troops, part of a 5,000 man force brought from Germany by the Hanover King of England to help subdue the highlanders. The monastery of the Black Friars that once dominated the battleground was already a distant memory, having been destroyed by a mob in the Reformation of 1559 after a particularly incendiary sermon by reformer John Knox.

After Culloden, an order was issued to seize all arms in the highlands, where Jacobite support had been strongest. Two of the weapons confiscated were swords from the North Inch battle held at the home of the MacIntosh chief. An appeal to the Duke of Cumberland brought a rare display of magnanimity and the relics were returned. Another trophy from the slaughter in Perth is the Feadan Dubh, the “Black Chanter” from the pipes carried by the Clan Chattan piper who killed his counterpart before expiring from his own wounds.

In one of a number of oral traditions concerning the chanter an ethereal piper appeared over the Clan Chattan during the battle at North Inch. After encouraging the fighting wildcats of Clan Chattan with several frenzied tunes the apparition dropped the pipes to the ground. The instrument, being made almost entirely of glass, shattered completely, except for the wooden chanter.

Conclusion

The unlikelihood of the savage struggle at Perth providing an end to a Highland feud must have been known to the royal court, and it has been suggested by some that the contest was never really intended to be more than a courtly diversion, a royal entertainment for visiting dignitaries from France and England. The prohibition on armor and shields suggests that the death of the participants was a desired result, perhaps in the hope that some steam might be taken out of the feud through the death of many leading warriors. That the clan chiefs and most of their leading men appear to have avoided the battle suggests that they fully understood this intention. The smoldering enmity that persisted between the Camerons and Clan Chattan well into the 19th century demonstrates that Scotland’s lowland nobility had once again failed to penetrate the psyche of their turbulent Gaelic neighbors.

The mass duel at Perth had little political legacy. Though the Scottish court may have been relieved to remove so many troublesome warriors from the scene in one day, both highland confederacies were large enough to withstand the loss. Neither side would have taken the result of the combat at Perth as a decision against them in their feud. The Norman rules of law that lay behind this judicial contest of arms were unknown in the highlands. There the code of blood revenge would have dictated further rounds of bloodletting in return for the deeds of that September afternoon. If the clans involved were indeed the Chattan and the Camerons, it is known that they were at each other’s throats once again early in the 15th century. There are records of a particularly ruthless attack on Palm Sunday, 1429, in which the Clan Chattan set fire to a church where a sept of Clan Cameron was gathered, killing most of those gathered within. The contenders for leadership of the Clan Chattan were not above fighting each other, as at the Battle of Glenlivet in 1594. The leadership dispute was eventually settled in court near the end of the 17th century, legal proceedings having replaced “battles to the death” by this time. The fact that the contest at Perth was largely ignored by official records after its conclusion and was never repeated would seem to confirm the ineffectiveness of this form of trial by combat as a means of dispute resolution amongst the highlanders.

Legends and Relics

Walter Scott’s 1828 account of the battle at North Inch features a remarkable display of devotion as the foster father and eight foster brothers of Eachin (‘Hector’, the son of the Clan Qwhele chief) sacrifice themselves to save the young man from the attacks of the Chattan warriors. As each falls in turn another foster-brother replaces the last with the cry “Another for Hector!” Scott’s version of the North Inch battle was never intended to be an historical account. The author always preferred vague and often disputed historical traditions as the basis of his stories.

In 1745 the Battle of Culloden brought an end to the Jacobite rebellion and dreams of a Stewart restoration in Britain. The Highland charge, which had triumphed so many times against English arms in the past, proved unequal that day to the disciplined fire and bayonet drill of the Duke of Cumberland’s army. Leading the Jacobite charge were the MacIntoshes of Clan Chattan, who left nearly their entire fighting strength in a mass graves on the battlefield. The Camerons were right behind them, their shot and bayonet-mangled bodies left intermingled with those of their ancient rivals. After the tragic finale to the “Rising of ’45,” the North Inch of Perth became home to a camp of Hessian troops, part of a 5,000 man force brought from Germany by the Hanover King of England to help subdue the highlanders. The monastery of the Black Friars that once dominated the battleground was already a distant memory, having been destroyed by a mob in the Reformation of 1559 after a particularly incendiary sermon by reformer John Knox.

After Culloden, an order was issued to seize all arms in the highlands, where Jacobite support had been strongest. Two of the weapons confiscated were swords from the North Inch battle held at the home of the MacIntosh chief. An appeal to the Duke of Cumberland brought a rare display of magnanimity and the relics were returned. Another trophy from the slaughter in Perth is the Feadan Dubh, the “Black Chanter” from the pipes carried by the Clan Chattan piper who killed his counterpart before expiring from his own wounds.

In one of a number of oral traditions concerning the chanter an ethereal piper appeared over the Clan Chattan during the battle at North Inch. After encouraging the fighting wildcats of Clan Chattan with several frenzied tunes the apparition dropped the pipes to the ground. The instrument, being made almost entirely of glass, shattered completely, except for the wooden chanter.

Conclusion

The unlikelihood of the savage struggle at Perth providing an end to a Highland feud must have been known to the royal court, and it has been suggested by some that the contest was never really intended to be more than a courtly diversion, a royal entertainment for visiting dignitaries from France and England. The prohibition on armor and shields suggests that the death of the participants was a desired result, perhaps in the hope that some steam might be taken out of the feud through the death of many leading warriors. That the clan chiefs and most of their leading men appear to have avoided the battle suggests that they fully understood this intention. The smoldering enmity that persisted between the Camerons and Clan Chattan well into the 19th century demonstrates that Scotland’s lowland nobility had once again failed to penetrate the psyche of their turbulent Gaelic neighbors.

Proudly powered by Weebly