Clan Chattan - Origin of the name

The origins of the name Chattan is disputed. There are three main theories

1. The name derives from the Catti, a tribe of Gauls, driven out by the advancing Romans.

A tribal leader named by the Seanchaí is Gilli Chattan Noir, chief of the Catti, during the reign of King Alpine (A.D. 831-834), from whom descend the general name of Chattan Clan. The ancient title (Celtic) of the Earls of Sutherland is “Morfhear chat,” Lord Cat; literally Greatman Cat.

2. The name is taken from Cait, an ancient name for the present counties of Caithness and Sutherland.

3. The clan derives its name from Gillchattan Mor, baillie of Ardchattan, follower of St Cattan. This is the more widely accepted theory.

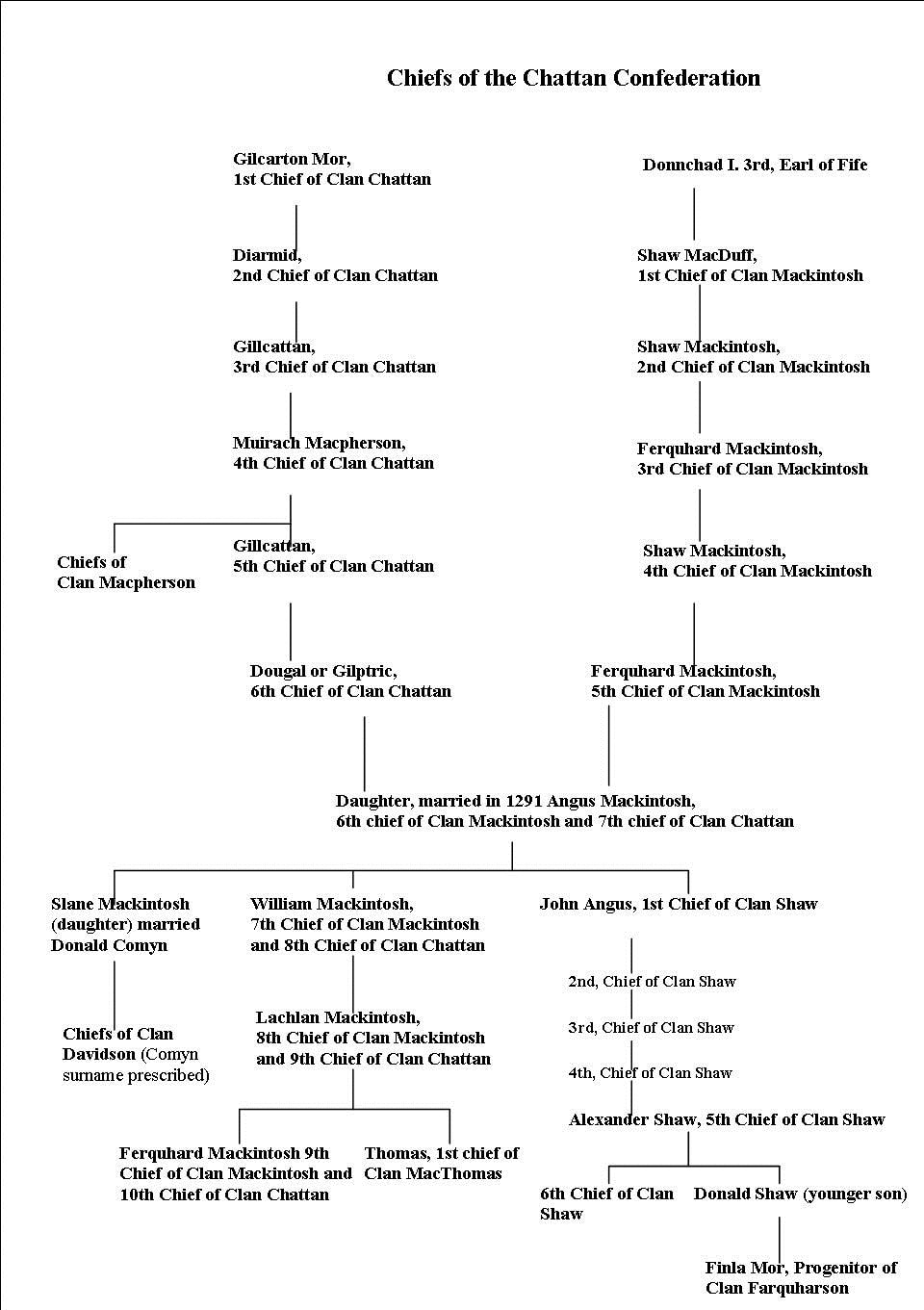

Until the early 14th century the Clan Chattan was a seperate Scottish clan with its own chieftencey, until Angus Mackintosh, 6th chief of Clan Mackintosh married Eva, the daughter of Gilpatric Dougal Dall, the 6th chief of Clan Chattan. Thus Angus Mackintosh became 6th chief of Clan Mackintosh and 7th chief of the Clan Chattan. The two clans united to form the Chattan Confederation, headed by the chief of Clan Mackintosh.

The following is a list of the traditional chiefs of the Clan Chattan before uniting with the Clan Mackintosh to form the Chattan Confederation:

Gillcarten Mor, first known chief of Clan Chattan

Diarmid

Gillicattan

Muirach

Gillicattan

Dougal or Gilpatric, daughter married 6th chief of Clan Mackintosh

Clan Davidson is a Pictish clan with Celtic roots, principally speaking, the major central highlands area where they hail from has of course been predominantly Celtic throughout the Dark Ages and into the Medieval period.

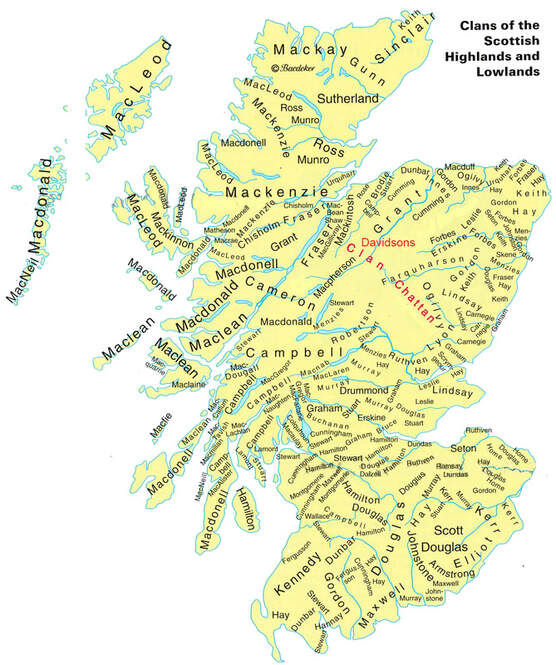

In the central highlands and the north especially, these were under the rule of petty Gaelic kings like Donald Lord of the Isles and the "Kings" of Moray.

It is believed that the Clan originated in the valley of the Spey River between the Cairngorm Mountains to the south and east and the Monadhliath Mountains to the north and west. The modern-day Scottish towns of Kingussie, Newtonmore and Avimore are located in the heart of the ancient Clan Davidson lands.

The origins of the name Chattan is disputed. There are three main theories

1. The name derives from the Catti, a tribe of Gauls, driven out by the advancing Romans.

A tribal leader named by the Seanchaí is Gilli Chattan Noir, chief of the Catti, during the reign of King Alpine (A.D. 831-834), from whom descend the general name of Chattan Clan. The ancient title (Celtic) of the Earls of Sutherland is “Morfhear chat,” Lord Cat; literally Greatman Cat.

2. The name is taken from Cait, an ancient name for the present counties of Caithness and Sutherland.

3. The clan derives its name from Gillchattan Mor, baillie of Ardchattan, follower of St Cattan. This is the more widely accepted theory.

Until the early 14th century the Clan Chattan was a seperate Scottish clan with its own chieftencey, until Angus Mackintosh, 6th chief of Clan Mackintosh married Eva, the daughter of Gilpatric Dougal Dall, the 6th chief of Clan Chattan. Thus Angus Mackintosh became 6th chief of Clan Mackintosh and 7th chief of the Clan Chattan. The two clans united to form the Chattan Confederation, headed by the chief of Clan Mackintosh.

The following is a list of the traditional chiefs of the Clan Chattan before uniting with the Clan Mackintosh to form the Chattan Confederation:

Gillcarten Mor, first known chief of Clan Chattan

Diarmid

Gillicattan

Muirach

Gillicattan

Dougal or Gilpatric, daughter married 6th chief of Clan Mackintosh

Clan Davidson is a Pictish clan with Celtic roots, principally speaking, the major central highlands area where they hail from has of course been predominantly Celtic throughout the Dark Ages and into the Medieval period.

In the central highlands and the north especially, these were under the rule of petty Gaelic kings like Donald Lord of the Isles and the "Kings" of Moray.

It is believed that the Clan originated in the valley of the Spey River between the Cairngorm Mountains to the south and east and the Monadhliath Mountains to the north and west. The modern-day Scottish towns of Kingussie, Newtonmore and Avimore are located in the heart of the ancient Clan Davidson lands.

The Davidsons did not invoke the pre fix Mac. This was a Gaelic tribe and one of the earliest to become associated with the Clan Chattan. The origin appears to be from David Dubh of Invernahaven. Their clan badge was stag’s head.

The Davison Chief settled in early time in Innvernahoven, a small estate in Badenoch where the Truim river meets the Spey River.

The main focus of Clan Davidson settlement in this part of the Spey Valley was for many centuries on the south side of the river, at Ruthven. A castle existed here from 1229 on the mound now occupied by the walls of Ruthven Barracks.

In 1010, Robert the chief of the Clan Cattan, fought against the Norsemen. He slew Comus, the Viking leader of the invaders, and gained a complete victory, for which Malcolm II gave him the lands of Keith in East-Lothian, the lands of Glenloy and Loch Arkaig. It was here that Tor Castle became the clan chief's seat.

Now, considering the Norman nobility being invited north by David I as an Anglicizing influence For David not only would have preferred Norman feudal law to Celtic, but also more importantly the laws of succession in Norman law as it would allow his immediate family to retain the throne of Scotland.

David used Norman lords to gain more control in the north, since he moved the capital of Scotland (his court actually) from the central highlands to the south, Edinburgh, which was closer to the Norman power base and gained lands in the central midlands in this way. Slowly pushing north.

According to the manuscript genealogies of Highland clans, believed to be written by MacLauchlan, bearing the date of 1467, contains the origin of the Davidsons attributed to a certain Gilliecattan Mhor, 1st chief of Clan Chattan in the time of 1085 –1153. The name of Gillechattan Mor, meant the great servant of St Catan, whose Abbey was at Kilchattan on the isle of Bute in the Firth of Clyde.

One of Gilliecattan Mhor’s great grandsons was named Muriach (or Murdoch) MacPherson who was parson of Kingussie in Badenoch. He became 4th Chief of Clan Chatten upon his brother's death. The name MacPherson, according to different spellings comes from the Gaelic Mac a’ Phearsain and means ‘Son of the Parson’. A Parson before the Reformation in Scotland, was not a priest, but the parson was the steward of church property, responsible for the collection of tithes.

Muriach’s great granddaughter married Angus MacKintosh in 1291, the 6th Chief of Clan MacKintosh and he would also become 7th Chief of Clan Chattan.

Angus’ daughter Slane MacKintosh, married Donald Cromyn , the third son of Robert Comyn who in turn was a grandson of John III Red Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, chief of the Clan Comyn. Their son was David Dubh, also known as Black David, in Gaelic Daibhidh Dhu, pronounced Davie Doo. David and his followers became known as the Clan Dhai because the Comyn name had already been prescribed in 1320. Unlike many Highland clan names which begin with the Gaelic 'mac' meaning 'son of', the son of David took the non-Gaelic form and became David-son. David Dubh of Invernahaven, Chief of Davidsons, having married the daughter of Angus, 6th of MacKintosh, sought the protection of his brother–in-law, William MacKintosh, 7th Chief of MacKintosh and 9th Chief of Clan Chattan, shortly before 1350, and thus Clan Davidson became part of the Chattan Confederation.

Who were the Comyns?

Origins of the Comyn Clan

This clan is believed to descend from Robert of Comyn, a companion of William the Conqueror who accompanied him in his conquest of England. Shortly after his participation in the Battle of Hastings, Robert was made Earl of Northumberland, and, when David I came to Scotland to claim his throne, Richard Comyn, the grandson of Robert, was among the Norman knights that followed him.

Richard Comyn quickly gained land and influence in Scotland through an advantageous marriage to the granddaughter of the former Scottish king Donald III, Hextilda of Tynedale.

Richard’s descendants continued the Comyns’ rise to power through marriage, and, at the close of the thirteenth century, the Comyns were the most powerful clan in Scotland. Family members were holding (or had held) at one time thirteen Scottish earldoms, including those of Buchan, Menteith, and Angus, and several lordships, including the Lordship of Badenoch. The Lords of Badenoch represented the chief line of the clan and ruled their vast lands from their impregnable island stronghold of Lochindorb Castle.

Like many of the new aristocracy of Scotland the Comyns arrived in the train of David I during the 1120s. William Cumin was David’s chancellor, and appears to have obtained advancement for his nephew Richard, prior to returning to England to pursue his ecclesiastical ambitions. Richard had lands in the north of England and was granted lands in southern Scotland by David; he also obtained further land by marriage to Hextilda. (Who was the granddaughter of Donald Bane, giving the Comyns their first claim to the Scottish throne). Throughout his life Richard’s importance to the Scottish crown grew, and the evidence indicates that he was a close advisor of David and his son Earl Henry, as well as Malcolm IV and William, increasing his land holding and being appointed justicair of Lothian in the 1170s.

By 1212 the Comyns had real power – the Comyn century had begun!

Following the successful suppression of the 1211 MacWilliam rebellion, the Comyns continued to expand their influence and land holdings. William Earl of Buchan, played an increasingly important part on the national scene, witnessing charters from places as widespread as the north of England, and Fyvie, in his own heartland.

He also played a key role in the coronation of Alexander II at Scone, in 1214 following the death of his father. Although the Comyns held lands throughout Scotland and England, William began to consolidate their power in the North East, and under his patronage Deer Abbey was founded in 1219. This consolidation an expansion continued in a relatively peaceful fashion until 1229 when another MacWilliam rebellion erupted out of Moray.

Alexander II, having failed to suppress the rebellion in person, again appointed William, the Warden of Moray, with the authority and resources to “get the job done”. The Comyns duly complied, and the heads of Gulleasbuig and his sons were delivered to the King, who in gratitude conferred the Lordship of Badenoch on William’s son Walter. The royal “enforcers” now directly controlled a swath of land across the breadth of northern Scotland, in the shape of the Lordships of Lochaber, Badenoch, and the Earldom of Buchan. This effectively stabilized the north for the crown and ended the MacWilliam threat for good.

So as another generation prepared to “assume the mantel”, they had the benefit of the huge support structure, created by Richard and William, based on, landholding, ties of marriage, and a large following of allied families, all of which made-up the formidable Comyn Party.

In the coming years this dominance would be challenged by rivals, but the Comyn party would work together to thwart the efforts of their various challengers.

When William the Earl of Buchan died in 1233, his son Walter, Earl of Mentieth and Lord of Badenoch, assumed the leadership and confronted the challenge from their north eastern neighbors, the Bissets and the Durwards.

The suspicious death of Patrick of Atholl in 1242, was the opportunity the Comyns needed to attack their Bisset challengers who had been gaining more influence with the King (Alexander II). Walter and John Bisset were implicated in the death and the Comyns, with the support of other nobles achieved the exile of the pair. Fleeing to England the Bissets encouraged the interference of Henry III in the affairs of Scotland, an unfortunate reality accepted by most in Scotland, but which would lead to disaster before the end of the century.

At the close of the reign of Alexander II, the Durwards rose to be the principle advisers to the king, and on his sudden death they retained control during the minority of Alexander III. The Comyns seized the young king and his queen taking control of the government, forcing out the Durwards. The Durwards sought Henry’s assistance, and again all were forced to accept his intervention. (It should be noted that Alexanders queen was Henry’s daughter, and he did have genuine concerns for her safety).

This is the period in which the later chroniclers paint the Comyns as “over mighty subjects”, but they were by then partisan Bruce/Stewart spin-doctors, and sought to unfairly discredit the Comyns. The Comyns have over the years received an extremely bad press and Alan Young set out to redress this balance and as he states in the conclusion of the first chapter;

“A Comyn perspective is necessary to test the Bruce–oriented version of thirteenth-century Scottish history and the Comyns’ traditional role in it as traitorous rivals to Robert Bruce”.

However one reviewer did remark that; even a book dedicated to the Comyn family history could not escape the shadow of Robert the Bruce in the title.

For the remainder of Alexander III’s reign the Comyns were prominent in the affairs of the realm, and on his untimely death were instrumental in stabilizing the situation and provided two of the Guardians of the realm during the first interregnum. (John II of Badenoch and Alexander Earl of Buchan).

Following the death of Margaret, the heir to the throne, the Comyns supported the Balliol claim, during the period of the “Great Cause”, in which Edward I was asked to adjudicate the claimants to the throne,

However, the Comyns also had a weak claim to the throne through Richard Comyn’s marriage to Hextilda, the daughter of king Donald Ban. John II of Badenoch also had a claim to the throne due to his marriage to Eleanor the sister of John Balliol, but that claim would always be subservient to that of John Balliol and his descendants.

Edward I (Longshanks) ruled in favor of John Balliol who became King of Scots, but Edward’s heavy-handed approach eventually lead to war.

The eastern central highland Clans, i.e., Clan Chattan and the Grants of Freuchy, had over an extended period - roughly from 1451 to 1609, interactions with the crown, and had formed relationships with successive kings and regional magnates, under varying political circumstances.

In stark contrast to the traditional identification of antagonistic crown-highlander relations, lack of highland responsiveness to crown initiatives and local instability. For brief periods, a harmonious and integrated history of interaction, in which the crown did not have to intervene directly but was able to govern through the co-operation of both its regional magnates, in this case the Gordon earls of Huntly and the Stewart earls of Moray, and its highland chiefs, the Mackintosh chiefs of Clan Chattan and the Grants of Freuchy.

Traditional clan policy had been one of adherence to the crown, usually through co-operation with regional authority.

However, one clan would not always act in the same way as another – and that within clans themselves, there were often significant differences.

Some inland clans, in contrast to some of the more remote western clans, were more integrated into lowland socio-political practices. King James VI himself drew a dividing line between those clans in Invernesshire that it would be more easy to civilize and the more barbarous clans of the outer isles.

For within the clans themselves, the nature of clan society, the inner workings of clan life and the role of the chieftains. The conglomeration of different kindreds, the Macphersons, Davidsons, Macgillivrays, Macleans and cadet Mackintosh branches within the Clan Chattan, all recognized the Mackintosh chieftain as their own. In the sixteenth century these were the Mackintoshes of Dunachton.

What these confederation of clans had in common were the ties of obligation that held them together, and loyal to their chieftains. These connections, however, were various. The links of kinship, and its inherent obligations of loyalty and service, obviously demonstrated within their subsidiary cadet branches, were not the only cohesive force that Clan Chattan could use to bind the structure of his clan.

Kinship became weaker the further removed from the chieftain's branch a clan member was: there was often little biological connection between a chieftain and his clansman – and this was particularly so within Clan Chattan.

The Comyns would consistently support the Scottish side during the war and John Comyn III, co-led the Scottish victory at Roslin in 1303, but about a year later the Comyns and the other Scottish magnates submitted to Edward, and it appeared the war was finally over.

But, two years later Robert the Bruce, murdered John "Red" Comyn, in Greyfriars church, the pivotal event that led to Scottish independence and consigned the Comyns to the historical dustbin.

Robert after numerous setbacks, eventually crushed the Earl of Buchan at Barra, and went on to totally destroy Comyn power. The taking of Castle Grant, 14th century; Originally a Comyn Clan stronghold, Clan Grant traditions tell us that the castle was taken from the Comyns by a combined force of the Grants and MacGregors. The Grants and MacGregors stormed the castle and in the process slew the Comyn Chief - and kept the Chief’s skull as a trophy of this victory. The skull of the Comyn was taken as a macabre trophy and was kept in Castle Grant and became an heirloom of the Clan

It is somewhat ironic that the Comyn family rose to power by crushing two campaigns, launched from Moray, to seize the Scottish throne, but were themselves destroyed by a third. Also, that the last senior male heir of the family, (John IV) who had for a century defended the Scottish crown should be killed fighting on the English side at Bannockburn.

John “the Black” Comyn

After the death of the last descendant of the royal line of David I, the clan chief John “the Black” Comyn was one of six competitors for the crown of Scotland due to his connection to King Donald III. A Comyn ally, John Balliol, was chosen as king, and Balliol’s sister was soon married to the Black Comyn.

John “the Red” Comyn and The Wars of Scottish Independence

This marriage produced a son, John “the Red” Comyn, and, upon the exile of the Balliols by Edward I of England, the Red Comyn was left as the most powerful man in Scotland and the legitimate royal successor, having a double claim through the male and female lines.

During the Wars of Scottish Independence John the Red acted as co-leader of the Scottish forces with his rival Robert the Bruce after the death of William Wallace and achieved some notable successes against the English, including at the Battle of Roslin. However, Robert the Bruce, desiring to secure his claim to the throne, murdered the Red Comyn at a meeting at a church in Dumfries in 1306. This led to a bitter civil war between the Bruce’s faction and the Comyns and their allies that eventually resulted in the Comyns’ power being completely broken at the Battle of Inverurie in 1308.

The Comyns, by the time of the War of Independence, were not only powerful because of their direct land holdings, but through a network of family connections. They were connected by marriage to Scottish royalty and many of the powerful families in both Scotland and England. How they rose to this position in a little over a century, and then fell within a decade, will be reviewed in a later post which was published in 1997, “Robert the Bruce’s Rivals: The Comyns, 1212 – 1314”,

This was critcal for their Davidson Clan’s survival because their ancestory was related to King John Balloil of Badenoch and they were part of a branch of the Comyns that was on the wrong side of history – enemies of Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, grandfather of Robert the Bruce.

When the power of the Comyns began to wane in Badenoch, Donald Dubh of Invernahaven, Chief of Davidsons, having married the daughter of Angus, 6th of MacKintosh, sought the protection of William, 7th of MacKintosh, before 1350, and the Clan Davidson became associated with the Chattan Confederation.

Safely under the protection of Clan Chattan, the Davidsons would grow into one of the most important of the families within the Chattan federation. Their land was located at Invernahavon, just north of the junction of the rivers Spey and Truim alongside the MacPhersons.

During the War of Independence with England, the clan sided with Robert I of Scotland, most likely due to the fact that MacKintosh’s enemy, John Comyn had declared for Edward Balliol. In reward for his fealty, MacKintosh was awarded the Comyn lands of Benchar in Badenoch in 1319.

During the 1745 Jacobite Rising, Angus, the chief of Clan MacKintosh was a captain in the Black Watch. Although traditionally the Clan supported the House of Stewart they had not declared for the Young Pretender. Angus’s wife, Anne, of Farquharson, successfully rallied the Chattan Confederation to the Jacobite cause.

Following the defeat at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 the Chattan Clan was severely diminished in strength and influence. In 1747

The Davison Chief settled in early time in Innvernahoven, a small estate in Badenoch where the Truim river meets the Spey River.

The main focus of Clan Davidson settlement in this part of the Spey Valley was for many centuries on the south side of the river, at Ruthven. A castle existed here from 1229 on the mound now occupied by the walls of Ruthven Barracks.

In 1010, Robert the chief of the Clan Cattan, fought against the Norsemen. He slew Comus, the Viking leader of the invaders, and gained a complete victory, for which Malcolm II gave him the lands of Keith in East-Lothian, the lands of Glenloy and Loch Arkaig. It was here that Tor Castle became the clan chief's seat.

Now, considering the Norman nobility being invited north by David I as an Anglicizing influence For David not only would have preferred Norman feudal law to Celtic, but also more importantly the laws of succession in Norman law as it would allow his immediate family to retain the throne of Scotland.

David used Norman lords to gain more control in the north, since he moved the capital of Scotland (his court actually) from the central highlands to the south, Edinburgh, which was closer to the Norman power base and gained lands in the central midlands in this way. Slowly pushing north.

According to the manuscript genealogies of Highland clans, believed to be written by MacLauchlan, bearing the date of 1467, contains the origin of the Davidsons attributed to a certain Gilliecattan Mhor, 1st chief of Clan Chattan in the time of 1085 –1153. The name of Gillechattan Mor, meant the great servant of St Catan, whose Abbey was at Kilchattan on the isle of Bute in the Firth of Clyde.

One of Gilliecattan Mhor’s great grandsons was named Muriach (or Murdoch) MacPherson who was parson of Kingussie in Badenoch. He became 4th Chief of Clan Chatten upon his brother's death. The name MacPherson, according to different spellings comes from the Gaelic Mac a’ Phearsain and means ‘Son of the Parson’. A Parson before the Reformation in Scotland, was not a priest, but the parson was the steward of church property, responsible for the collection of tithes.

Muriach’s great granddaughter married Angus MacKintosh in 1291, the 6th Chief of Clan MacKintosh and he would also become 7th Chief of Clan Chattan.

Angus’ daughter Slane MacKintosh, married Donald Cromyn , the third son of Robert Comyn who in turn was a grandson of John III Red Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, chief of the Clan Comyn. Their son was David Dubh, also known as Black David, in Gaelic Daibhidh Dhu, pronounced Davie Doo. David and his followers became known as the Clan Dhai because the Comyn name had already been prescribed in 1320. Unlike many Highland clan names which begin with the Gaelic 'mac' meaning 'son of', the son of David took the non-Gaelic form and became David-son. David Dubh of Invernahaven, Chief of Davidsons, having married the daughter of Angus, 6th of MacKintosh, sought the protection of his brother–in-law, William MacKintosh, 7th Chief of MacKintosh and 9th Chief of Clan Chattan, shortly before 1350, and thus Clan Davidson became part of the Chattan Confederation.

Who were the Comyns?

Origins of the Comyn Clan

This clan is believed to descend from Robert of Comyn, a companion of William the Conqueror who accompanied him in his conquest of England. Shortly after his participation in the Battle of Hastings, Robert was made Earl of Northumberland, and, when David I came to Scotland to claim his throne, Richard Comyn, the grandson of Robert, was among the Norman knights that followed him.

Richard Comyn quickly gained land and influence in Scotland through an advantageous marriage to the granddaughter of the former Scottish king Donald III, Hextilda of Tynedale.

Richard’s descendants continued the Comyns’ rise to power through marriage, and, at the close of the thirteenth century, the Comyns were the most powerful clan in Scotland. Family members were holding (or had held) at one time thirteen Scottish earldoms, including those of Buchan, Menteith, and Angus, and several lordships, including the Lordship of Badenoch. The Lords of Badenoch represented the chief line of the clan and ruled their vast lands from their impregnable island stronghold of Lochindorb Castle.

Like many of the new aristocracy of Scotland the Comyns arrived in the train of David I during the 1120s. William Cumin was David’s chancellor, and appears to have obtained advancement for his nephew Richard, prior to returning to England to pursue his ecclesiastical ambitions. Richard had lands in the north of England and was granted lands in southern Scotland by David; he also obtained further land by marriage to Hextilda. (Who was the granddaughter of Donald Bane, giving the Comyns their first claim to the Scottish throne). Throughout his life Richard’s importance to the Scottish crown grew, and the evidence indicates that he was a close advisor of David and his son Earl Henry, as well as Malcolm IV and William, increasing his land holding and being appointed justicair of Lothian in the 1170s.

By 1212 the Comyns had real power – the Comyn century had begun!

Following the successful suppression of the 1211 MacWilliam rebellion, the Comyns continued to expand their influence and land holdings. William Earl of Buchan, played an increasingly important part on the national scene, witnessing charters from places as widespread as the north of England, and Fyvie, in his own heartland.

He also played a key role in the coronation of Alexander II at Scone, in 1214 following the death of his father. Although the Comyns held lands throughout Scotland and England, William began to consolidate their power in the North East, and under his patronage Deer Abbey was founded in 1219. This consolidation an expansion continued in a relatively peaceful fashion until 1229 when another MacWilliam rebellion erupted out of Moray.

Alexander II, having failed to suppress the rebellion in person, again appointed William, the Warden of Moray, with the authority and resources to “get the job done”. The Comyns duly complied, and the heads of Gulleasbuig and his sons were delivered to the King, who in gratitude conferred the Lordship of Badenoch on William’s son Walter. The royal “enforcers” now directly controlled a swath of land across the breadth of northern Scotland, in the shape of the Lordships of Lochaber, Badenoch, and the Earldom of Buchan. This effectively stabilized the north for the crown and ended the MacWilliam threat for good.

So as another generation prepared to “assume the mantel”, they had the benefit of the huge support structure, created by Richard and William, based on, landholding, ties of marriage, and a large following of allied families, all of which made-up the formidable Comyn Party.

In the coming years this dominance would be challenged by rivals, but the Comyn party would work together to thwart the efforts of their various challengers.

When William the Earl of Buchan died in 1233, his son Walter, Earl of Mentieth and Lord of Badenoch, assumed the leadership and confronted the challenge from their north eastern neighbors, the Bissets and the Durwards.

The suspicious death of Patrick of Atholl in 1242, was the opportunity the Comyns needed to attack their Bisset challengers who had been gaining more influence with the King (Alexander II). Walter and John Bisset were implicated in the death and the Comyns, with the support of other nobles achieved the exile of the pair. Fleeing to England the Bissets encouraged the interference of Henry III in the affairs of Scotland, an unfortunate reality accepted by most in Scotland, but which would lead to disaster before the end of the century.

At the close of the reign of Alexander II, the Durwards rose to be the principle advisers to the king, and on his sudden death they retained control during the minority of Alexander III. The Comyns seized the young king and his queen taking control of the government, forcing out the Durwards. The Durwards sought Henry’s assistance, and again all were forced to accept his intervention. (It should be noted that Alexanders queen was Henry’s daughter, and he did have genuine concerns for her safety).

This is the period in which the later chroniclers paint the Comyns as “over mighty subjects”, but they were by then partisan Bruce/Stewart spin-doctors, and sought to unfairly discredit the Comyns. The Comyns have over the years received an extremely bad press and Alan Young set out to redress this balance and as he states in the conclusion of the first chapter;

“A Comyn perspective is necessary to test the Bruce–oriented version of thirteenth-century Scottish history and the Comyns’ traditional role in it as traitorous rivals to Robert Bruce”.

However one reviewer did remark that; even a book dedicated to the Comyn family history could not escape the shadow of Robert the Bruce in the title.

For the remainder of Alexander III’s reign the Comyns were prominent in the affairs of the realm, and on his untimely death were instrumental in stabilizing the situation and provided two of the Guardians of the realm during the first interregnum. (John II of Badenoch and Alexander Earl of Buchan).

Following the death of Margaret, the heir to the throne, the Comyns supported the Balliol claim, during the period of the “Great Cause”, in which Edward I was asked to adjudicate the claimants to the throne,

However, the Comyns also had a weak claim to the throne through Richard Comyn’s marriage to Hextilda, the daughter of king Donald Ban. John II of Badenoch also had a claim to the throne due to his marriage to Eleanor the sister of John Balliol, but that claim would always be subservient to that of John Balliol and his descendants.

Edward I (Longshanks) ruled in favor of John Balliol who became King of Scots, but Edward’s heavy-handed approach eventually lead to war.

The eastern central highland Clans, i.e., Clan Chattan and the Grants of Freuchy, had over an extended period - roughly from 1451 to 1609, interactions with the crown, and had formed relationships with successive kings and regional magnates, under varying political circumstances.

In stark contrast to the traditional identification of antagonistic crown-highlander relations, lack of highland responsiveness to crown initiatives and local instability. For brief periods, a harmonious and integrated history of interaction, in which the crown did not have to intervene directly but was able to govern through the co-operation of both its regional magnates, in this case the Gordon earls of Huntly and the Stewart earls of Moray, and its highland chiefs, the Mackintosh chiefs of Clan Chattan and the Grants of Freuchy.

Traditional clan policy had been one of adherence to the crown, usually through co-operation with regional authority.

However, one clan would not always act in the same way as another – and that within clans themselves, there were often significant differences.

Some inland clans, in contrast to some of the more remote western clans, were more integrated into lowland socio-political practices. King James VI himself drew a dividing line between those clans in Invernesshire that it would be more easy to civilize and the more barbarous clans of the outer isles.

For within the clans themselves, the nature of clan society, the inner workings of clan life and the role of the chieftains. The conglomeration of different kindreds, the Macphersons, Davidsons, Macgillivrays, Macleans and cadet Mackintosh branches within the Clan Chattan, all recognized the Mackintosh chieftain as their own. In the sixteenth century these were the Mackintoshes of Dunachton.

What these confederation of clans had in common were the ties of obligation that held them together, and loyal to their chieftains. These connections, however, were various. The links of kinship, and its inherent obligations of loyalty and service, obviously demonstrated within their subsidiary cadet branches, were not the only cohesive force that Clan Chattan could use to bind the structure of his clan.

Kinship became weaker the further removed from the chieftain's branch a clan member was: there was often little biological connection between a chieftain and his clansman – and this was particularly so within Clan Chattan.

The Comyns would consistently support the Scottish side during the war and John Comyn III, co-led the Scottish victory at Roslin in 1303, but about a year later the Comyns and the other Scottish magnates submitted to Edward, and it appeared the war was finally over.

But, two years later Robert the Bruce, murdered John "Red" Comyn, in Greyfriars church, the pivotal event that led to Scottish independence and consigned the Comyns to the historical dustbin.

Robert after numerous setbacks, eventually crushed the Earl of Buchan at Barra, and went on to totally destroy Comyn power. The taking of Castle Grant, 14th century; Originally a Comyn Clan stronghold, Clan Grant traditions tell us that the castle was taken from the Comyns by a combined force of the Grants and MacGregors. The Grants and MacGregors stormed the castle and in the process slew the Comyn Chief - and kept the Chief’s skull as a trophy of this victory. The skull of the Comyn was taken as a macabre trophy and was kept in Castle Grant and became an heirloom of the Clan

It is somewhat ironic that the Comyn family rose to power by crushing two campaigns, launched from Moray, to seize the Scottish throne, but were themselves destroyed by a third. Also, that the last senior male heir of the family, (John IV) who had for a century defended the Scottish crown should be killed fighting on the English side at Bannockburn.

John “the Black” Comyn

After the death of the last descendant of the royal line of David I, the clan chief John “the Black” Comyn was one of six competitors for the crown of Scotland due to his connection to King Donald III. A Comyn ally, John Balliol, was chosen as king, and Balliol’s sister was soon married to the Black Comyn.

John “the Red” Comyn and The Wars of Scottish Independence

This marriage produced a son, John “the Red” Comyn, and, upon the exile of the Balliols by Edward I of England, the Red Comyn was left as the most powerful man in Scotland and the legitimate royal successor, having a double claim through the male and female lines.

During the Wars of Scottish Independence John the Red acted as co-leader of the Scottish forces with his rival Robert the Bruce after the death of William Wallace and achieved some notable successes against the English, including at the Battle of Roslin. However, Robert the Bruce, desiring to secure his claim to the throne, murdered the Red Comyn at a meeting at a church in Dumfries in 1306. This led to a bitter civil war between the Bruce’s faction and the Comyns and their allies that eventually resulted in the Comyns’ power being completely broken at the Battle of Inverurie in 1308.

The Comyns, by the time of the War of Independence, were not only powerful because of their direct land holdings, but through a network of family connections. They were connected by marriage to Scottish royalty and many of the powerful families in both Scotland and England. How they rose to this position in a little over a century, and then fell within a decade, will be reviewed in a later post which was published in 1997, “Robert the Bruce’s Rivals: The Comyns, 1212 – 1314”,

This was critcal for their Davidson Clan’s survival because their ancestory was related to King John Balloil of Badenoch and they were part of a branch of the Comyns that was on the wrong side of history – enemies of Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, grandfather of Robert the Bruce.

When the power of the Comyns began to wane in Badenoch, Donald Dubh of Invernahaven, Chief of Davidsons, having married the daughter of Angus, 6th of MacKintosh, sought the protection of William, 7th of MacKintosh, before 1350, and the Clan Davidson became associated with the Chattan Confederation.

Safely under the protection of Clan Chattan, the Davidsons would grow into one of the most important of the families within the Chattan federation. Their land was located at Invernahavon, just north of the junction of the rivers Spey and Truim alongside the MacPhersons.

During the War of Independence with England, the clan sided with Robert I of Scotland, most likely due to the fact that MacKintosh’s enemy, John Comyn had declared for Edward Balliol. In reward for his fealty, MacKintosh was awarded the Comyn lands of Benchar in Badenoch in 1319.

During the 1745 Jacobite Rising, Angus, the chief of Clan MacKintosh was a captain in the Black Watch. Although traditionally the Clan supported the House of Stewart they had not declared for the Young Pretender. Angus’s wife, Anne, of Farquharson, successfully rallied the Chattan Confederation to the Jacobite cause.

Following the defeat at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 the Chattan Clan was severely diminished in strength and influence. In 1747

Proudly powered by Weebly