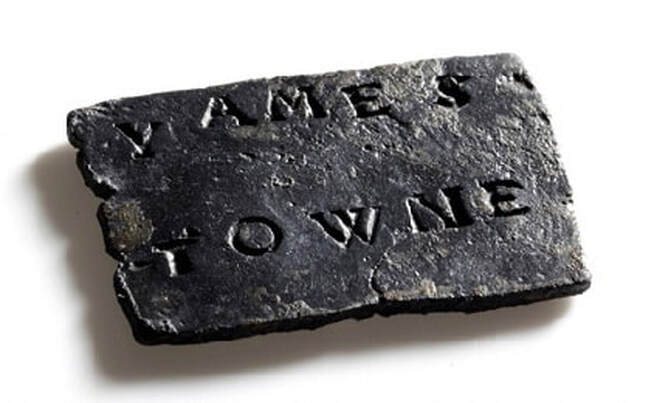

Following two failed English attempts to establish settlements in North America – the Roanoke Colony in Virginia and the Popham Colony in Maine – the Jamestown settlement was established in Virginia in 1607. The following year two supply missions were sent from England, however, due to a lack of experience and resources, the colony was threatened by disease, starvation and warfare with Native Americans.

The investors of the Jamestowne Venture, the Virginia Company of London had been promising big rewards for their speculative investors. With the dismal results, they expressed their frustrations and demands upon the leaders at Jamestowne in written form. They specifically demanded that the colonists send commodities sufficient enough to pay the cost of a 3rd supply voyage. It fell to the Jamestowne’s third president to deliver a reply. The ever bold, Captain John Smith delivered what must have been a wake-up call to the investors in London. In what has been termed "Smith's Rude Answer", John Smith began his letter with something of an apology, saying "I humbly intreat your Pardons if I offend you with my rude Answer... When you send againe I entreat you rather send but thirty Carpenters, husbandmen, gardiners, fishermen, blacksmiths, masons and diggers up of trees, roots, well provided; than a thousand of such awe have: for except wee be able both to lodge them and feed them, the most will consume with want of necessaries before they can be made good for anything."

The London Company comprehended and embraced Smith's message. They quickly organized their Third Supply mission, it was by far the largest and best equipped yet. They even had a new purpose-built flagship constructed, the Sea Venture, placed in the most experienced of hands, Christopher Newport and Admiral Sir George Somers.

Samuel Jordan’s experience fighting the Spaniards and a willingness for adventure made him an ideal candidate for employment in the New World. His military experience would later prove invaluable withstanding the Indian massacre of 1622.

In June of 1609, he set sail from Plymouth Harbor, bound for Virginia with Admiral Sir George Somers and Sir Thomas Gates in a fleet of eight ships known as the company’s “Third Supply” bound for the New World.. These three men were on the new flagship of the Virginia Company, called the Sea Venture, and were unwittingly embarking on an adventure later immortalized by William Shakespeare in his play, "The Tempest".

The London Company comprehended and embraced Smith's message. They quickly organized their Third Supply mission, it was by far the largest and best equipped yet. They even had a new purpose-built flagship constructed, the Sea Venture, placed in the most experienced of hands, Christopher Newport and Admiral Sir George Somers.

Samuel Jordan’s experience fighting the Spaniards and a willingness for adventure made him an ideal candidate for employment in the New World. His military experience would later prove invaluable withstanding the Indian massacre of 1622.

In June of 1609, he set sail from Plymouth Harbor, bound for Virginia with Admiral Sir George Somers and Sir Thomas Gates in a fleet of eight ships known as the company’s “Third Supply” bound for the New World.. These three men were on the new flagship of the Virginia Company, called the Sea Venture, and were unwittingly embarking on an adventure later immortalized by William Shakespeare in his play, "The Tempest".

January 1609, The Construction of the Flagship Sea Venture

In response to the inadequacy of its previous vessels, the Sea Venture as England's first purpose-designed emigrant ship. She displaced 300 tons, cost £1,500, and differed from her naval contemporaries primarily in her internal arrangements. Her guns were placed on her main deck, rather than below decks as was then the norm. This meant the ship did not need double-timbering, as she was the first single-timbered, armed merchant ship built in England. The hold was sheathed and furnished for passengers. She was armed with eight nine pounder demi-culverins, eight five-pounder sakers, four three pounder falcons, and four arquebusses. The ship’s journey to Jamestown was to be her maiden voyage.

On May 15, 1609 Samuel Jordan boarded the Sea Venture or (also listed as Sea Adventure), flagship of the Third Supply and the newest vessel of the fleet of eight other ships, they departed London under the command of Admiral Sir George Somers. On May 20, the fleet anchored at Plymouth, England to take on supplies. Leaving Plymouth, the fleet was forced to seek shelter from high winds at Falmouth on June 2. Among other notables aboard with Samuel Jordan, were Sir Thomas Gates, who was to be the new Governor for the struggling colony at Jamestown. Also on board was John Rolfe, who later introduced the cultivation of tobacco into Virginia and married the Indian Princess, Pocahontas. Another passenger aboard the Sea Venture was Stephen Hopkins, who would later also be a passenger on the Mayflower to Plymouth, MA.

In response to the inadequacy of its previous vessels, the Sea Venture as England's first purpose-designed emigrant ship. She displaced 300 tons, cost £1,500, and differed from her naval contemporaries primarily in her internal arrangements. Her guns were placed on her main deck, rather than below decks as was then the norm. This meant the ship did not need double-timbering, as she was the first single-timbered, armed merchant ship built in England. The hold was sheathed and furnished for passengers. She was armed with eight nine pounder demi-culverins, eight five-pounder sakers, four three pounder falcons, and four arquebusses. The ship’s journey to Jamestown was to be her maiden voyage.

On May 15, 1609 Samuel Jordan boarded the Sea Venture or (also listed as Sea Adventure), flagship of the Third Supply and the newest vessel of the fleet of eight other ships, they departed London under the command of Admiral Sir George Somers. On May 20, the fleet anchored at Plymouth, England to take on supplies. Leaving Plymouth, the fleet was forced to seek shelter from high winds at Falmouth on June 2. Among other notables aboard with Samuel Jordan, were Sir Thomas Gates, who was to be the new Governor for the struggling colony at Jamestown. Also on board was John Rolfe, who later introduced the cultivation of tobacco into Virginia and married the Indian Princess, Pocahontas. Another passenger aboard the Sea Venture was Stephen Hopkins, who would later also be a passenger on the Mayflower to Plymouth, MA.

THE TEMPEST

ON JULY 25, 1609, having nearly crossed the Atlantic, the sailors of the Sea-Venture scanned the horizon and spotted danger. With the convoy of eight other vessels, they spied a tempest—or what the Carib Indians called a hurricane— with torrential rain, violent waves and winds above 74 miles per hour, moving swiftly towards them. As the storm worsened, the ketch (small sailboat with 2 masts) was cut free and never recovered. The storm separated the Sea Venture from the rest of the fleet. After four days of being in the storm, the Sea Venture began to take on water.

With “the clouds gathering thick upon us and the winds singing and whistling most unusually,” wrote passenger William Strachey, “a dreadful storm and hideous began to blow from the northeast, which, swelling and roaring as it were by fits, some hours with more violence than others, at length did beat all light from Heaven; which like an hell of darkness, turned black upon us, so much the fuller of horror and fear use to overrun the troubled and overmastered senses of all, which taken up with amazement, the ears lay so sensible to the terrible cries and murmurs of the winds and distraction of our company as who was most armed and best prepared was not a little shaken.”

ON JULY 25, 1609, having nearly crossed the Atlantic, the sailors of the Sea-Venture scanned the horizon and spotted danger. With the convoy of eight other vessels, they spied a tempest—or what the Carib Indians called a hurricane— with torrential rain, violent waves and winds above 74 miles per hour, moving swiftly towards them. As the storm worsened, the ketch (small sailboat with 2 masts) was cut free and never recovered. The storm separated the Sea Venture from the rest of the fleet. After four days of being in the storm, the Sea Venture began to take on water.

With “the clouds gathering thick upon us and the winds singing and whistling most unusually,” wrote passenger William Strachey, “a dreadful storm and hideous began to blow from the northeast, which, swelling and roaring as it were by fits, some hours with more violence than others, at length did beat all light from Heaven; which like an hell of darkness, turned black upon us, so much the fuller of horror and fear use to overrun the troubled and overmastered senses of all, which taken up with amazement, the ears lay so sensible to the terrible cries and murmurs of the winds and distraction of our company as who was most armed and best prepared was not a little shaken.”

Unbeknownst to them, the Sea Venture had a critical flaw in her newness, as her timbers had not set. The caulking had been forced from between them, and the ship began to leak rapidly. All hands were required for bailing, but the water continued to rise in the hold.

The tempest fury “startled and turned the blood and took down the braves of the most hardy mariner of them all.” The less hardy passengers aboard the ninety-eight-foot, three-hundred-ton vessel cried out in fear, but their words were “drowned in the winds and the winds in the thunder.” The shaken seamen recovered and went to work as the ship’s timbers began to groan. Six to eight men together struggled to steer the vessel. Others cut down the rigging and sails to lessen resistance to the wind; they threw luggage and ordnance overboard to lighten the load and reduce the risk of capsizing. They crept, candles in hand, along the ribs of the ship, searching and listening for weeping leaks, stopping as many as they could, using beef when they ran out of oakum. Water nonetheless gushed into the ship, rising several feet, above two tiers of hogsheads, in the hold. The crew and passengers pumped continuously during “an Egyptian night of three days of perpetual horror, with the common sort stripped naked as men in Galleys.” Even gentlemen who had never worked took turns pumping, while those who could not pump bailed with kettles and buckets. They had no food and no rest as they pumped an estimated two thousand tons of water out of the leaky vessel.

It was not enough. The waterline did not recede, and the people at the pumps had reached the limits of their strength, endurance, and hope. Now that the exhausted sailors had done all that was humanly possible to resist the apocalyptic force of the hurricane, they took comfort in a ritual of the sea, turning the maritime world upside down as they faced certain death. Defying the strictures of private property and the authority of Captain Christopher Newport, as well as the Virginia Company gentlemen such as Sir George Somers and Sir Thomas Gates, they broke open the ship’s liquors and in one last expression of solidarity “drunk one to the other, taking their last leave one of the other until their more joyful and happy meeting in a more blessed world.”

The Admiral of the Company, Sir George Somers himself, was at the helm through the storm. When he spied land on the morning of 28 July, the water in the hold had risen to nine feet and crew and passengers had been driven past the point of exhaustion. Somers, within sight of land off the coast of "the uninhabited and dreaded Island of Devils" deliberately drove the ship onto the reefs in order to prevent its foundering. On July 28, the ship was forced fortunately bow first, and was caught between two sections of reef less than a mile from shore. For three days and nights the crew of the Sea Venture worked to keep the ship on the rocks. The ship's guns were reportedly jettisoned (though two were salvaged later) to raise her buoyancy, but this only delayed the inevitable.

Wedged on the craggy shore the Sea Venture was wrecked, yet miraculously without loss of life, between two great rocks in the islands of what would be later called, Isle of Bermuda on July 28. The 150 wet and terrified crew and passengers, men and women originally intended by the Virginia Company of London as reinforcements for the company's new plantation, straggled onto the strange shore, a place long considered by Spaniards to be an enchanted “Isle of Devils” infested with demons and monsters, and a ghoulish graveyard for passing European ships. The Isle was charted in 1511 but shunned by seafarers for a century, it was known mostly through the accounts of a few mariners, renegades, and castaways, such as Job Hortop, who had escaped galley slavery in the Spanish West Indies, passed by the island, and made it to London to tell his tale. The eeriness of the place owed much to the harsh, hollow howling of nocturnal birds called Cahows, whose shrieks haunted the crews of passing ships.

Of the original nine ships, one sank. Wedged into the craggy shore, the Sea Venture was secured long enough for the crew and all passengers, including one dog, to escape along with most of their cargo.

The reality in Bermuda, as the shipwrecked seafarers soon discovered, was entirely different from its reputation. The island, in their view, turned out to be Eden, a land of perpetual spring and abundant food, “the richest, health-fullest and pleasantest [place] they ever saw.” The would-be colonists feasted on black hogs that had swum ashore and multiplied after Spanish shipwrecks years earlier. There was an abundance of fish, (grouper, parrot fish, red snapper) that could be literally be caught by hand or with a stick with a bent nail, fowl that would land on a man’s or woman’s arms or shoulders or on massive tortoises that would feed fifty, and on an array of delicious fruit.

The tempest fury “startled and turned the blood and took down the braves of the most hardy mariner of them all.” The less hardy passengers aboard the ninety-eight-foot, three-hundred-ton vessel cried out in fear, but their words were “drowned in the winds and the winds in the thunder.” The shaken seamen recovered and went to work as the ship’s timbers began to groan. Six to eight men together struggled to steer the vessel. Others cut down the rigging and sails to lessen resistance to the wind; they threw luggage and ordnance overboard to lighten the load and reduce the risk of capsizing. They crept, candles in hand, along the ribs of the ship, searching and listening for weeping leaks, stopping as many as they could, using beef when they ran out of oakum. Water nonetheless gushed into the ship, rising several feet, above two tiers of hogsheads, in the hold. The crew and passengers pumped continuously during “an Egyptian night of three days of perpetual horror, with the common sort stripped naked as men in Galleys.” Even gentlemen who had never worked took turns pumping, while those who could not pump bailed with kettles and buckets. They had no food and no rest as they pumped an estimated two thousand tons of water out of the leaky vessel.

It was not enough. The waterline did not recede, and the people at the pumps had reached the limits of their strength, endurance, and hope. Now that the exhausted sailors had done all that was humanly possible to resist the apocalyptic force of the hurricane, they took comfort in a ritual of the sea, turning the maritime world upside down as they faced certain death. Defying the strictures of private property and the authority of Captain Christopher Newport, as well as the Virginia Company gentlemen such as Sir George Somers and Sir Thomas Gates, they broke open the ship’s liquors and in one last expression of solidarity “drunk one to the other, taking their last leave one of the other until their more joyful and happy meeting in a more blessed world.”

The Admiral of the Company, Sir George Somers himself, was at the helm through the storm. When he spied land on the morning of 28 July, the water in the hold had risen to nine feet and crew and passengers had been driven past the point of exhaustion. Somers, within sight of land off the coast of "the uninhabited and dreaded Island of Devils" deliberately drove the ship onto the reefs in order to prevent its foundering. On July 28, the ship was forced fortunately bow first, and was caught between two sections of reef less than a mile from shore. For three days and nights the crew of the Sea Venture worked to keep the ship on the rocks. The ship's guns were reportedly jettisoned (though two were salvaged later) to raise her buoyancy, but this only delayed the inevitable.

Wedged on the craggy shore the Sea Venture was wrecked, yet miraculously without loss of life, between two great rocks in the islands of what would be later called, Isle of Bermuda on July 28. The 150 wet and terrified crew and passengers, men and women originally intended by the Virginia Company of London as reinforcements for the company's new plantation, straggled onto the strange shore, a place long considered by Spaniards to be an enchanted “Isle of Devils” infested with demons and monsters, and a ghoulish graveyard for passing European ships. The Isle was charted in 1511 but shunned by seafarers for a century, it was known mostly through the accounts of a few mariners, renegades, and castaways, such as Job Hortop, who had escaped galley slavery in the Spanish West Indies, passed by the island, and made it to London to tell his tale. The eeriness of the place owed much to the harsh, hollow howling of nocturnal birds called Cahows, whose shrieks haunted the crews of passing ships.

Of the original nine ships, one sank. Wedged into the craggy shore, the Sea Venture was secured long enough for the crew and all passengers, including one dog, to escape along with most of their cargo.

The reality in Bermuda, as the shipwrecked seafarers soon discovered, was entirely different from its reputation. The island, in their view, turned out to be Eden, a land of perpetual spring and abundant food, “the richest, health-fullest and pleasantest [place] they ever saw.” The would-be colonists feasted on black hogs that had swum ashore and multiplied after Spanish shipwrecks years earlier. There was an abundance of fish, (grouper, parrot fish, red snapper) that could be literally be caught by hand or with a stick with a bent nail, fowl that would land on a man’s or woman’s arms or shoulders or on massive tortoises that would feed fifty, and on an array of delicious fruit.

*NOTE: There has been considerable debate on various forums regarding the validity of Samuel Jordan sailing on the Sea Venture in the Third Supply Armada. But we do know is that Samuel Jordan was given the title of Ancient Planter, meaning he departed England in 1609 and arrived in Jamestown in 1610 and thus having 10 years time invested he was given a land grant in 1619 by the governor and also acknowledged by King James himself. We also know the Sea Venture had 150 passengers onboard when it departed from Plymouth, England. On 23 July. The hurricane at sea separated the Sea Venture from the other vessels in the Armada. After four days of furiously bailing out water, she still had 9 feet of water in the hull and it was rising. She was going to sink, but land was miraculously sited and she was scuttled between two reefs off the shores of Bermuda on 28 July 1609. Incredibly all of the 150 passengers safely made land, even the dog!

Unfortunately, the only copy of a manifest of those passengers onboard the Sea Venture accounts for only 50, and that was complied by memory some 9-10 years after the voyage. We will never absolutely know for sure regarding Samuel Jordan passage, since the original papers are lost at sea.

Unfortunately, the only copy of a manifest of those passengers onboard the Sea Venture accounts for only 50, and that was complied by memory some 9-10 years after the voyage. We will never absolutely know for sure regarding Samuel Jordan passage, since the original papers are lost at sea.

1626 Map of Bermuda

Much to the chagrin of the shipwrecked officers of the Virginia Company, Bermuda caused many of them utterly to forgo any desire to ever leave for Virginia, they lived in such plenty, peace and ease. Surviving the storm, the people had found their paradise! - their land of plenty, and they began “to settle a foundation of forever inhabiting there”. They considered it “a more joyful and happy meeting in a more blessed world” after all.

It is not surprising that the shipwrecked passengers responded as they did, for they had been told to expect paradise at the end of their journey. In his “Ode to the Virginian Voyage” (1606), Michael Drayton had insisted that “the New World was Earth’s only Paradise. Where nature hath in store fowl, venison, and fish; And the fruitfull’st soil without your toil, three harvests more and all greater than you wish!”

Instead of devils and sea monsters, the settlers were met with crystal clear waters and in place of spirits they found much needed spiritual sustenance and serenity to continue their journey. Signed S'el Jourdan, in his account of the Sea Venture shipwreck, described Bermuda saying, “it hath been and is still accounted, the most dangerous, infortunate, and most forlorn place in the world, it is in truth the richest, healthfullest, and pleasing land.” How deceiving the reputation of the The Devils Isle had been!

William Strachey, secretary-elect of Virginia and passenger aboard the Sea Venture, in his letter describing the 1609 shipwreck said it best, “The Devils Isles…are feared and avoided of all sea travellers alive, above any other place in the world. Yet it pleased our merciful God, to make even this hideous and hated place both the place of our safety and means of our deliverance.”

How ironic that a place once condemned as an isle of devils would serve as salvation for the English colony of Virginia and play such a pivotal role in the settlement of one of the world’s greatest nations. How interesting that this same island that was feared by “all sea travellers alive” would be a top ten holiday destination, visited by major cruise lines and regarded as one of the most peaceful and tranquil places on earth.

Instead of devils and sea monsters, the settlers were met with crystal clear waters and in place of spirits they found much needed spiritual sustenance and serenity to continue their journey. Signed S'el Jourdan, in his account of the Sea Venture shipwreck, described Bermuda saying, “it hath been and is still accounted, the most dangerous, infortunate, and most forlorn place in the world, it is in truth the richest, healthfullest, and pleasing land.” How deceiving the reputation of the The Devils Isle had been!

William Strachey, secretary-elect of Virginia and passenger aboard the Sea Venture, in his letter describing the 1609 shipwreck said it best, “The Devils Isles…are feared and avoided of all sea travellers alive, above any other place in the world. Yet it pleased our merciful God, to make even this hideous and hated place both the place of our safety and means of our deliverance.”

How ironic that a place once condemned as an isle of devils would serve as salvation for the English colony of Virginia and play such a pivotal role in the settlement of one of the world’s greatest nations. How interesting that this same island that was feared by “all sea travellers alive” would be a top ten holiday destination, visited by major cruise lines and regarded as one of the most peaceful and tranquil places on earth.

After nearly a year being on Bermuda the survivors at the behest of the Virginia Company officers, managed to build two small pinnacles named the "Patience" and the "Deliverance" using the salvaged wreckage of the Sea Venture for their construction. These two small vessels were to carry them the rest of the way to Virginia.

It had been intended to build only one vessel, the Deliverance, but it soon became evident that she would not be large enough to carry the settlers and all of the food (salted pork) that was being sourced on the islands. While the new ships were under construction, the Sea Venture 's longboat was fitted with a mast and sent ahead under the command of Henry Raven to find Virginia. The boat and its crew were never seen again.

Other members of the expedition had died before the Deliverance and the Patience could set sail on 10 May 1610. Among those left buried in Bermuda were the wife and child of John Rolfe, soon to be founder of the Virginia's tobacco industry, and who would find his new wife in the New World, the Powhatan princess Pocahontas. Two men, Carter and Waters, were also left behind to maintain the claim of the islands for England, but the remaining members including Samuel Jordan arrived in Jamestown on 23 May.

Sir Thomas Gates had a cross erected before leaving Bermuda, on which was a copper tablet inscribed in Latin and English:

In Memory of our deliverance both from the Storme and the Great leake wee have erected this cross to the honour of God. It is the Spoyle of an English Shippe of 300 tonnes called SEA VENTURE bound with seven others (from which the storme divided us) to Virginia or NOVA BRITANIA in America. In it were two Knights, Sir Thomas Gates, Knight Gouvenor of the English Forces and Colonie there: and Sir George Somers, Knight Admiral of the Seas. Her Captain was Christopher Newport. Passengers and mariners she had beside (which all come to safety) one hundred and fiftie. Wee were forced to runne her ashore (by reason of her leake) under a point that bore South East from the Northerne Point of the Island which wee discovered first on the eighth and twentieth of July 1609.

This was not the end of their ordeal, however. Upon reaching Jamestowne, they found only 60 survivors remained of the 500 who had preceded them. All hope had been given up by those waiting in Virginia, and it was a very brief joyful reunion for the families of those presumed lost to the sea 12 months before.

It had been intended to build only one vessel, the Deliverance, but it soon became evident that she would not be large enough to carry the settlers and all of the food (salted pork) that was being sourced on the islands. While the new ships were under construction, the Sea Venture 's longboat was fitted with a mast and sent ahead under the command of Henry Raven to find Virginia. The boat and its crew were never seen again.

Other members of the expedition had died before the Deliverance and the Patience could set sail on 10 May 1610. Among those left buried in Bermuda were the wife and child of John Rolfe, soon to be founder of the Virginia's tobacco industry, and who would find his new wife in the New World, the Powhatan princess Pocahontas. Two men, Carter and Waters, were also left behind to maintain the claim of the islands for England, but the remaining members including Samuel Jordan arrived in Jamestown on 23 May.

Sir Thomas Gates had a cross erected before leaving Bermuda, on which was a copper tablet inscribed in Latin and English:

In Memory of our deliverance both from the Storme and the Great leake wee have erected this cross to the honour of God. It is the Spoyle of an English Shippe of 300 tonnes called SEA VENTURE bound with seven others (from which the storme divided us) to Virginia or NOVA BRITANIA in America. In it were two Knights, Sir Thomas Gates, Knight Gouvenor of the English Forces and Colonie there: and Sir George Somers, Knight Admiral of the Seas. Her Captain was Christopher Newport. Passengers and mariners she had beside (which all come to safety) one hundred and fiftie. Wee were forced to runne her ashore (by reason of her leake) under a point that bore South East from the Northerne Point of the Island which wee discovered first on the eighth and twentieth of July 1609.

This was not the end of their ordeal, however. Upon reaching Jamestowne, they found only 60 survivors remained of the 500 who had preceded them. All hope had been given up by those waiting in Virginia, and it was a very brief joyful reunion for the families of those presumed lost to the sea 12 months before.

Proudly powered by Weebly