"Over there, over there,

Send the word, send the word over there

That the Yanks are coming, the Yanks are coming

The drums rum-tumming everywhere.

So prepare, say a prayer,

Send the word, send the word to beware –

We'll be over, we're coming over,

And we won't come back till it's over, over there."

Send the word, send the word over there

That the Yanks are coming, the Yanks are coming

The drums rum-tumming everywhere.

So prepare, say a prayer,

Send the word, send the word to beware –

We'll be over, we're coming over,

And we won't come back till it's over, over there."

For many Americans the attack on the Lusitania in May 1915 and death of an estimated 1,198 innocent lives including 128 Americans, solidified the belief that Germany was a brutal, degenerate monarchy. The sinking of that British ocean liner by a German torpedo began the push for American Protectionism and the United States of America for entering World War I On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson addressed Congress, asking for a declaration of war against Germany. Just over two months earlier, on January 31, the German government had announced its resumption of “unrestricted submarine warfare.” With the announcement, German U-boats would without warning attempt to sink all ships traveling to or from British or French ports. This war would be dominated by mass industrially made lethal technology, like no war had witnessed before. That meant the death of millions on European battlefields, making U.S. soldiers badly needed to fill the depleted trenches of France. The fight on Western Front had settled into a battle of attrition, marked by a long series of trench lines that changed little over the course of four years of fighting.

A race for time ensued–the Army had only 25,000 regulars in 1917 and needed thousands more to fight in France. The “Draft” was revived and many men, levied from Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Wyoming and Montana, would have to be inprocessed, clothed, armed, and trained.

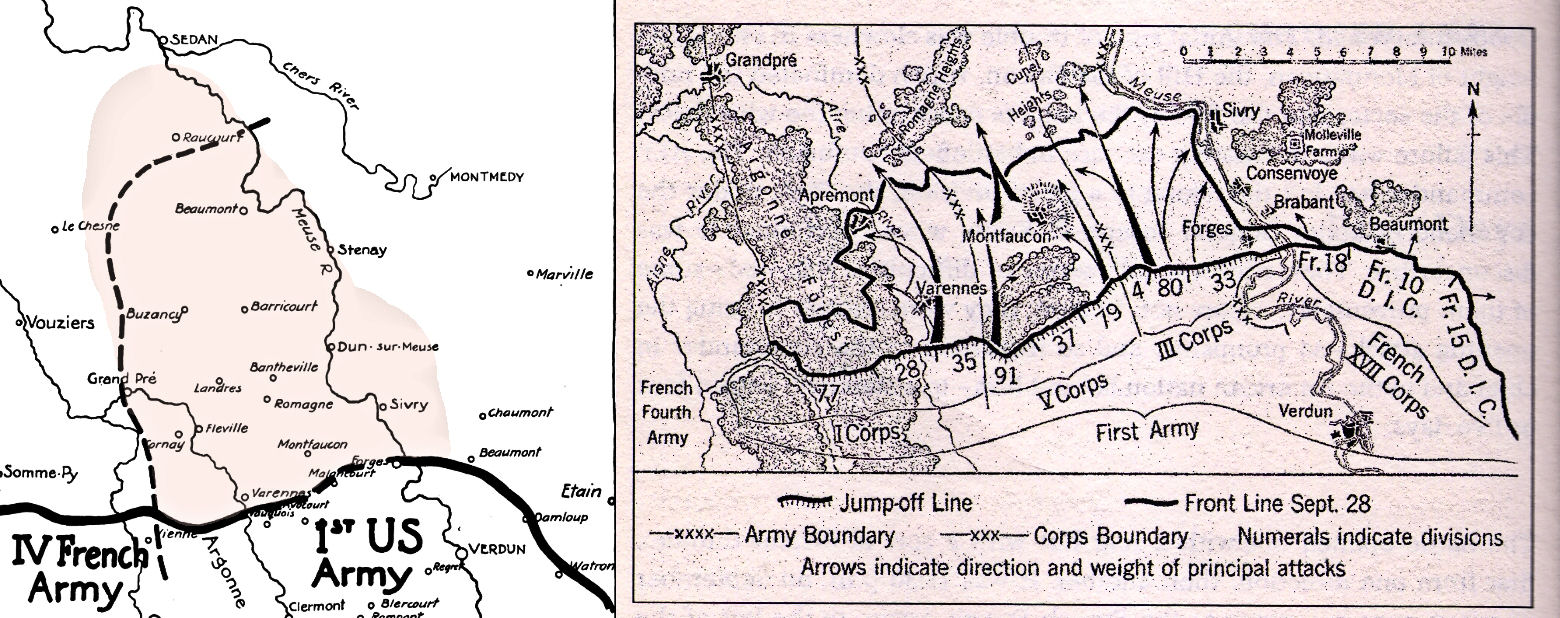

The 91st Infantry Division (“Wild West” Division – battle cry: “Powder River! Let’er Buck!”) trained at Camp Lewis from 5 September 1917 until it shipped out, on 21-24 June 1918, for France, where it served with distinction.

The 91st Infantry Division (“Wild West” Division – battle cry: “Powder River! Let’er Buck!”) trained at Camp Lewis from 5 September 1917 until it shipped out, on 21-24 June 1918, for France, where it served with distinction.

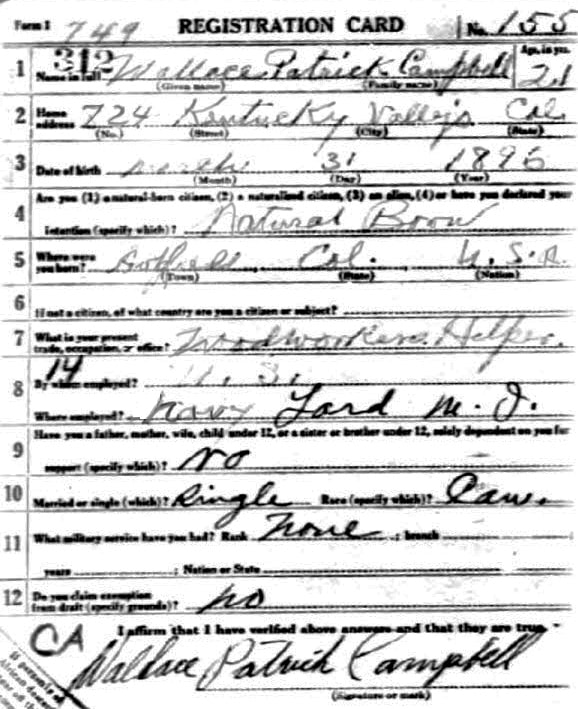

Wallace Patrick Campbell, enlisted Sept. 18th 1917 at Fairfield, Ca. He served as a Private, Company J, Battalion, 182nd Brigade, 363rd Regiment, 91st Infantry Division, V Corps, American First Army.

Combat Training at Camp Lewis, Tacoma, Washington 1917

The 91st Infantry Division was a National Army Division. Based at Camp Lewis, Washington, it was composed of men from the western United States. The 91st Infantry Division was famously nicknamed as the "Wild West Division” with a Fir Tree as its Division insignia to symbolize its traditional home of the Far West. This nickname referred to the many cowboys, ranch hands and the overall western attitude within the division.

"We arrived in Tacoma in September, with conscripts and enlisted men from the nine Western states and Alaska territory.

Camp Lewis was prepared for us and we started drilling immediately. Our division, the Wild West Division but officially known as the 91st, was given an insignia inspired by the Wild West: a green fir tree circled in red with a red 91 on center. We were proud to be the first American Army division formed in America and the first to be shooting in France.”

The boys from Wild West Division excelled at everything, the mock trench battles, open warfare training, rifle fixed bayonets and hand to hand combat, and of course many were expert marksmen and experienced shooters.

They needed some good Western passwords. They chose “Powder River”—a broad and dangerous looking stretch of wide water and coal-blackened sand running through Eastern Montana and Northern Wyoming. Not as formidable as believed at first sight, being actually only a few inches deep. A fitting thought while facing the Hun. It became a popular battle cry and coupled it with “let ‘er buck”....the universal command of every ready-mounted Bronco Buster from corral to rodeo chute: Powder River - Let ‘er Buck became the war Whoop, a battle cry, a motto, their cheer. The motto of the French Army was, “they shall not pass”. The 91st replaced that three year-old watch word with the Wild West equivalent of let’s go...."Let’er Buck”

Combat Training at Camp Lewis, Tacoma, Washington 1917

The 91st Infantry Division was a National Army Division. Based at Camp Lewis, Washington, it was composed of men from the western United States. The 91st Infantry Division was famously nicknamed as the "Wild West Division” with a Fir Tree as its Division insignia to symbolize its traditional home of the Far West. This nickname referred to the many cowboys, ranch hands and the overall western attitude within the division.

"We arrived in Tacoma in September, with conscripts and enlisted men from the nine Western states and Alaska territory.

Camp Lewis was prepared for us and we started drilling immediately. Our division, the Wild West Division but officially known as the 91st, was given an insignia inspired by the Wild West: a green fir tree circled in red with a red 91 on center. We were proud to be the first American Army division formed in America and the first to be shooting in France.”

The boys from Wild West Division excelled at everything, the mock trench battles, open warfare training, rifle fixed bayonets and hand to hand combat, and of course many were expert marksmen and experienced shooters.

They needed some good Western passwords. They chose “Powder River”—a broad and dangerous looking stretch of wide water and coal-blackened sand running through Eastern Montana and Northern Wyoming. Not as formidable as believed at first sight, being actually only a few inches deep. A fitting thought while facing the Hun. It became a popular battle cry and coupled it with “let ‘er buck”....the universal command of every ready-mounted Bronco Buster from corral to rodeo chute: Powder River - Let ‘er Buck became the war Whoop, a battle cry, a motto, their cheer. The motto of the French Army was, “they shall not pass”. The 91st replaced that three year-old watch word with the Wild West equivalent of let’s go...."Let’er Buck”

It is here in Tacoma, that Wallace Patrick Campbell meets Mabelle Winefred Watson, resident of Tacoma, Pierce County, Washington. Despite the unpredictable weather, while on leave Walter (Wally) not only got to see the lush beautiful country and mountains (which was a far cry from the mining towns of Jerome, AZ and Goldfield, Nevada where his father worked as Miner. Wally meets and courts Mabelle Watson.

Training at Camp Lewis was arduous, monotonous, and discouraging. Time and again, when the ranks of the company would be filled and the men proficient in elementary drill, detachments would be taken away and sent to other units. New and raw recruits would fill the vacated ranks, and it would be necessary to go back to rudimentary drill again.

Since each unit was responsible to train individual personnel in initial drills, the collective regiment training program was in a state of disarray. As a result, the requirement to be competent in individual drill superseded collective training opportunities and this had a negative impact on the “Wild West” division. Their collective training was limited to mass formation marches around the training areas at Camp Lewis. Leaders in the division were taught how to march troops, but there was little focus on developing skills such as assaulting machine gun nests or coordinating fire missions with the artillery–tactics that were needed to be successful on the battlefields in Europe.

One of the most important individual skills was marksmanship, and the men of the 91st focused much of their training time on weapons proficiency. By December 1917, most of the weapons for the division arrived and the live training at the Camp Lewis ranges began in earnest. Incentives to perform well at the ranges included a badge, extra pay, and bragging rights. Soldiers began on short ranges up to 300 yards, with and without bayonet. Those who did well advanced to the 500 and 1000 yard course. The 91st also focused heavily on marksmanship at night.

The training environment in western Washington State provided Private First Class Walter P Campbell with some unique challenges. Through November and December, it was raining nearly the entire time for 5 weeks. He didn’t have to be out in it all the time but all the same it made it miserable. In March 1918, it was snowing and raining. It would snow an inch or two then rain for an hour or so and melt it all, then repeat the performance. The weather at Camp Lewis may not have been popular with the recruits, but there could not have been a more realistic training environment to prepare them for what they would soon face in France.

Sixteen weeks of drill and training concentrated at the individual, squad, and company levels. Upon successful completion of the first sixteen weeks, units were supposed to progress to battalion and higher level exercises. Although the manual did briefly mentioned open warfare, it stressed that “training for trench warfare is of paramount importance,” and required each cantonment area to construct a system of trenches to use for training.

This implication of a more defensive focus ignited a debate on how to properly train the new Army. Pershing wanted training to focus on the basics of the infantry: the rifle and the bayonet. He also advocated for training on open warfare tactics as opposed to a defensive, trench warfare mindset. “All training behind the line must be specially directed towards offensive action.”

This regulation stressed three types of warfare that soldiers must train for: the initial attack against well-organized and long established positions, attacks against improvised defenses following successful assaults on the original main positions, and finally, open warfare.

Different companies were assigned sectors of the range, marched stealthily into the trenches, and as a huge searchlight in imitation of the star shells on the battlefield was flashed for a moment along the targets, a heavy burst of fire came from the alert men in those sectors.”36 Another range allowed for a small size live fire range where a squad moved through unknown terrain and engaged pop-up targets at various ranges. The leaders of the 91st clearly maximized training opportunities on individual weapons and the proficiency gained through this training at Camp Lewis would benefit them greatly in the trenches of France.

Training at Camp Lewis was arduous, monotonous, and discouraging. Time and again, when the ranks of the company would be filled and the men proficient in elementary drill, detachments would be taken away and sent to other units. New and raw recruits would fill the vacated ranks, and it would be necessary to go back to rudimentary drill again.

Since each unit was responsible to train individual personnel in initial drills, the collective regiment training program was in a state of disarray. As a result, the requirement to be competent in individual drill superseded collective training opportunities and this had a negative impact on the “Wild West” division. Their collective training was limited to mass formation marches around the training areas at Camp Lewis. Leaders in the division were taught how to march troops, but there was little focus on developing skills such as assaulting machine gun nests or coordinating fire missions with the artillery–tactics that were needed to be successful on the battlefields in Europe.

One of the most important individual skills was marksmanship, and the men of the 91st focused much of their training time on weapons proficiency. By December 1917, most of the weapons for the division arrived and the live training at the Camp Lewis ranges began in earnest. Incentives to perform well at the ranges included a badge, extra pay, and bragging rights. Soldiers began on short ranges up to 300 yards, with and without bayonet. Those who did well advanced to the 500 and 1000 yard course. The 91st also focused heavily on marksmanship at night.

The training environment in western Washington State provided Private First Class Walter P Campbell with some unique challenges. Through November and December, it was raining nearly the entire time for 5 weeks. He didn’t have to be out in it all the time but all the same it made it miserable. In March 1918, it was snowing and raining. It would snow an inch or two then rain for an hour or so and melt it all, then repeat the performance. The weather at Camp Lewis may not have been popular with the recruits, but there could not have been a more realistic training environment to prepare them for what they would soon face in France.

Sixteen weeks of drill and training concentrated at the individual, squad, and company levels. Upon successful completion of the first sixteen weeks, units were supposed to progress to battalion and higher level exercises. Although the manual did briefly mentioned open warfare, it stressed that “training for trench warfare is of paramount importance,” and required each cantonment area to construct a system of trenches to use for training.

This implication of a more defensive focus ignited a debate on how to properly train the new Army. Pershing wanted training to focus on the basics of the infantry: the rifle and the bayonet. He also advocated for training on open warfare tactics as opposed to a defensive, trench warfare mindset. “All training behind the line must be specially directed towards offensive action.”

This regulation stressed three types of warfare that soldiers must train for: the initial attack against well-organized and long established positions, attacks against improvised defenses following successful assaults on the original main positions, and finally, open warfare.

Different companies were assigned sectors of the range, marched stealthily into the trenches, and as a huge searchlight in imitation of the star shells on the battlefield was flashed for a moment along the targets, a heavy burst of fire came from the alert men in those sectors.”36 Another range allowed for a small size live fire range where a squad moved through unknown terrain and engaged pop-up targets at various ranges. The leaders of the 91st clearly maximized training opportunities on individual weapons and the proficiency gained through this training at Camp Lewis would benefit them greatly in the trenches of France.

It was under these circumstances that the 91st Infantry Division departed for war in Europe. Although many Soldiers arrived nearly ten months prior to departure, there was excessive turnover throughout the training period. The men of the 91st division trained individual skills such as marksmanship relatively well, but the ability to execute more advanced combined arms tactics was severely limited. There was some debate within the War Department about how the Army should focus its training in the United States.

Major General John J. Pershing was in command of the AEF for the entire war. Pershing insisted that American soldiers be well-trained before going to Europe. As a result, few troops arrived before January 1918. In addition, Pershing insisted that the American force would not be used merely to fill gaps in the French and British armies, and he resisted European efforts to have U.S. troops deployed as individual replacements in decimated Allied units. His approach was not well received by the western Allied leaders who distrusted the potential of an army lacking experience in large-scale warfare.

Major General John J. Pershing was in command of the AEF for the entire war. Pershing insisted that American soldiers be well-trained before going to Europe. As a result, few troops arrived before January 1918. In addition, Pershing insisted that the American force would not be used merely to fill gaps in the French and British armies, and he resisted European efforts to have U.S. troops deployed as individual replacements in decimated Allied units. His approach was not well received by the western Allied leaders who distrusted the potential of an army lacking experience in large-scale warfare.

The Americans Arrive.

In July of 1918, elements of the 91st began arriving at their assigned training areas in France, there were already approximately 17 AEF divisions ahead of them in the training process. While in France, the 91st Division had conducted additional training, but the AEF pushed it to the front lines before it was completed. These men were young and inexperienced, but they were eager to get into the fight. The decision involved the future operations of more than a million Americans. To the question General Pershing replied without hesitation: "Most assuredly: but as an American army and in no other way."

By June 1917, there were only 14,000 American soldiers in France, and the AEF had only a minor participation at the front through late October 1917. But by May 1918 over one million American troops were now stationed in France, though only half of them actually made it to the front lines. The Allied Army had gain overwhelming superiority in front-line rifle strength as American soldiers arrive by that summer.

The mobilization effort taxed the American military to the limit and required new organizational strategies and command structures to transport great numbers of troops and supplies quickly and efficiently. The French harbors of Bordeaux, La Pallice, Saint Nazaire, and Brest became the entry points into the French railway system that brought the American troops and their supplies to the Western Front. American engineers in France also built 82 new ship berths, nearly 1,000 miles of additional standard-gauge tracks, and over 100,000 miles of telephone and telegraph lines.

By June 1917, there were only 14,000 American soldiers in France, and the AEF had only a minor participation at the front through late October 1917. But by May 1918 over one million American troops were now stationed in France, though only half of them actually made it to the front lines. The Allied Army had gain overwhelming superiority in front-line rifle strength as American soldiers arrive by that summer.

The mobilization effort taxed the American military to the limit and required new organizational strategies and command structures to transport great numbers of troops and supplies quickly and efficiently. The French harbors of Bordeaux, La Pallice, Saint Nazaire, and Brest became the entry points into the French railway system that brought the American troops and their supplies to the Western Front. American engineers in France also built 82 new ship berths, nearly 1,000 miles of additional standard-gauge tracks, and over 100,000 miles of telephone and telegraph lines.

Within certain levels of military technology, the United States was well-prepared. The basic infantrymen of the U.S. Army and Marine Corps were equipped with the Model 1903 Springfield rifle. Developed after the Americans experience against the German-made Mausers in the Spanish American War, it was an excellent firearm, equal or superior to any rifle in the world at the time.

But, unfortunately, Machine guns were another matter. In 1912, American inventor Isaac Lewis had offered to give the U.S. Army his air-cooled machine gun design for free. When he was rejected, Lewis sold the design to Britain and Belgium, where it was mass-produced and used throughout the war.

With the Pacifist Movement fully entrenched and a newly elected liberal President Woodrow Wilson in place, he persuaded his colleagues to boldly critique any buildup to the war, and the war itself, as a profiteering mission in which the only parties sure to benefit were industrialists.

The eventual failure of the Pacifist Movement to keep the nation out of war obscures the fact that it did succeed, from 1914 to early 1917, in delaying U.S. involvement by building a broad coalition that was firmly rooted both in electoral politics and in social movements for equality, especially the suffragist movement.

However, because of the attack on the ocean liner Lusitania along with escalating nationalism made the declaration of war all but inevitable, The high-minded rationale of Wilson, thought it best to positioned himself and the nation - as the redemptive forces that would bring about a just peace and prepare the soil in which democracy could take root across Europe.

Unfortunately, with far more soldiers than supplies of modern machine guns, the U.S. Army had to adopt several systems of foreign design, including the less-than-desirable French Chauchat, which tended to jam in combat and proved difficult to maintain in the trenches.

American soldiers fared better with the Great War’s truly new innovation, the tank. Developed from the need to successfully cross “No Man’s Land” and clear enemy-held trenches, the tank had been used with limited success in 1917 by the British and the French. Both nations had combat-ready machines available for American troops.

But, unfortunately, Machine guns were another matter. In 1912, American inventor Isaac Lewis had offered to give the U.S. Army his air-cooled machine gun design for free. When he was rejected, Lewis sold the design to Britain and Belgium, where it was mass-produced and used throughout the war.

With the Pacifist Movement fully entrenched and a newly elected liberal President Woodrow Wilson in place, he persuaded his colleagues to boldly critique any buildup to the war, and the war itself, as a profiteering mission in which the only parties sure to benefit were industrialists.

The eventual failure of the Pacifist Movement to keep the nation out of war obscures the fact that it did succeed, from 1914 to early 1917, in delaying U.S. involvement by building a broad coalition that was firmly rooted both in electoral politics and in social movements for equality, especially the suffragist movement.

However, because of the attack on the ocean liner Lusitania along with escalating nationalism made the declaration of war all but inevitable, The high-minded rationale of Wilson, thought it best to positioned himself and the nation - as the redemptive forces that would bring about a just peace and prepare the soil in which democracy could take root across Europe.

Unfortunately, with far more soldiers than supplies of modern machine guns, the U.S. Army had to adopt several systems of foreign design, including the less-than-desirable French Chauchat, which tended to jam in combat and proved difficult to maintain in the trenches.

American soldiers fared better with the Great War’s truly new innovation, the tank. Developed from the need to successfully cross “No Man’s Land” and clear enemy-held trenches, the tank had been used with limited success in 1917 by the British and the French. Both nations had combat-ready machines available for American troops.

The regiment was bivouac for the night in the Forest de Hesse just a short distance from German front lines. Here at the Regiment lay quietly under harassing shellfire of the Germans for six days in dugouts, camouflage shelters tents and improvised shelters.

On September 25 orders we received that the division would attack the next morning at 5:30 AM. At 7 o’clock that night the regiment started to march into position in the front line trenches. At midnight the Allied Artillery bombardment began and as each whistling shell was on its way to the German defenses it was given a silent cheer by the men of the regiment as they waited in the trenches.

"Over the Top"

At 5:30 AM on the morning of September 26, 1918 the 363 infantry with the 181st infantry brigade on there right and the 138th infantry on their left, went “over the top” down from the shell towards slope‘s of Mt. des Allieux into no man’s land. There was a heavy fog that hung over the landscape. The rolls of barbed wire in front of the French trenches was thick, high and uncut. Ten minutes after going over the top the advancing companies found it impossible to keep contact with each other in the fog. Even Platoon leaders were unable to keep their commands together for by this time to smoke barrage that had been laid down had added to the obscurity and one was able to see but only a few yards ahead.

Scattered but undaunted bands up infantrymen rush ford that’s across no man’s land forwarded to create that rent close to the front of the German trenches leapt over the German Barbwire and jumped into his trenches were a few of the remaining Germans had survived the American barrage and who were waiting for the Yanks.

These Germans were quickly disposed of and the Americans with orders to proceed with all haste went on into Bois De Cheppy - like packs of hounds after rabbits.

As the first waves of the regiment cleared the north edge of the woods the fog lifted in the first real resistance was met - enemy machine nests and gunners, snipers and artillery firing at point blank range. Here officers and men of the regiment began to fall and here in the space up just a few minutes, it was learned that their threatening flanking moments against the Germans strong points with a continued and determined advance we’re bringing the Germans out of battle their positions to surrender with hands raised and cries of “Kamerad”.

Prisoners began to pour back into the American lines. One company captured three field pieces 2 of which were still firing. The 363rd had advance into the artillery positions and the Germans were in an disorganize route. The regimen advance continued. The town of Very was captured and the scattered companies of the first and second battalions we’re moving again strengthening resistance on the slopes north and east of Very when night fell and the order came to withdraw and hold the slopes north and east of town.

The men had found their first day of battle to be one of sport they went after snipers concealed in bushes and trees as one would go on a quail hunt. But the second and succeeding days with the enemy throwing his full weight and all available strength against the attack which threaten Sedan and most important lines of communication on the Western front the battle settled into a yard by yard gain - hanging on under shell and machine gun fire.

The roads in the rear where shell torn and jammed with traffic, food and supplies were slow in getting up to the lines. The men were hungry, water which scarce, the nights were rainy, there was no shelter. At times the regiment had to throw in all of its units to fill gaps that appeared in the line but held a wide front. But the Germans were stopped at every counterattack, not an inch of ground was lost to them.

The regiment had made good and it’s very first battle it had not only done all that was expected but had extended it’s flanks and had thrown in troops were other units have been held back and needed assistance. The officers and the men were exhausted after nine days of fighting when they were relieved October 5, 1918

The fighting was extreme with charges and counter charges, point blank fire. Grenades and bayonets. It rained day and night. After some ten days of extreme fighting we were sent back a few miles to a rest billet and rolling kitchen. Before we had been deluged, the order came down that we had to get back. The general offensive was starting! The Argonne Forest where our 362nd was almost wiped out from Buck to Brass”

So as not to give away our strength and positions all troops and equipment were moved out at night by trucks and horse and wagons sloshing through the rain and deep mud and always under a barrage of constant shelling. Fear of being seen and destroyed, our rolling field kitchens would hide in the Woods all day and serve us only at night under darkness. Many on kitchen duty were nonetheless killed or wounded keeping hot coffee ready for our battle weary troops. Heavy traffic on those muddy, crowded clogged roads kept our ambulances bogged down.

Our wounded had to shelter for days in dugouts or the bombed-out cellars of Very. Our wounded who could walk, staggered back through the lines towards the field hospitals. Our critically wounded. Outdoor only just sit propped up against trees and wait . We became used to the constant ear-splitting barrage of overhead artillery and exploding shells; we never became used to the terror filled screams of the wounded horses, never.

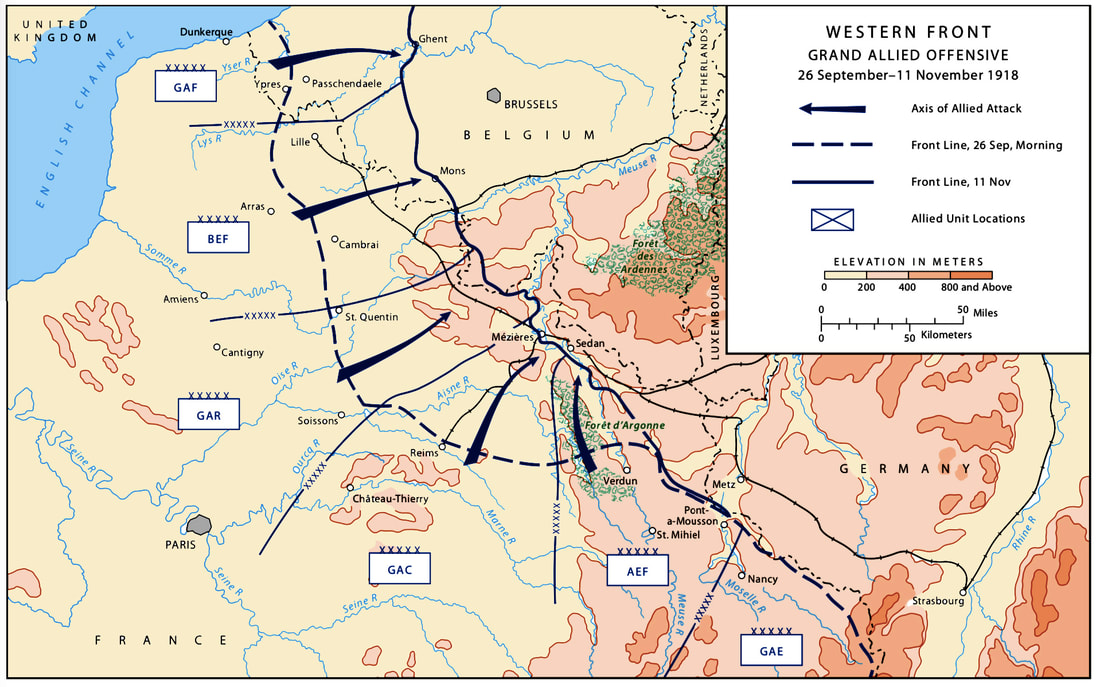

The attack on St-Mihiel, 12 September proved quite successful, The American Army quickly occupied the salient, capturing 450 guns and 16,000 prisoners at the cost of 7,000 casualties. The “next show” turned out to be the Meuse-Argonne, the battle that ultimately helped change the course of the war and contributed to the surrender of the German forces. By far, the Meuse-Argonne was the single most deadly battle for United States forces.

This forty-seven day slaughter claimed the lives of 26,277 Americans and wounded an additional 95,786 out of the 1.2 million who fought. Here the 91st Division fought on the front lines of the Meuse- Argonne. In the first days of this battle, the 91st Division, although inexperienced, gained more ground than any other American division units flanks. However, it paid a heavy price in terms of American lives.

Each of the German positions was skillfully organized in depth covered with elaborate belts of barbed wire and supported by concrete machine-gun and artillery emplacements which provided alternative protected positions for those weapons. All that could be done to improve observation posts. signal communications. routes, trails and light railway to assist the defense received meticulous attention by German engineer troops before and throughout the operations. In addition to the fully developed positions above mentioned were other partly organized defense lines which were intensively improved as need for their use increased. With Turkey. Bulgaria. and Austria on the verge of collapse. Germany's only remaining hope was to stave off defeat by dogged fighting on French soil until the Allies would grant favorable peace terms.

Each of the German positions was skillfully organized in depth covered with elaborate belts of barbed wire and supported by concrete machine-gun and artillery emplacements which provided alternative protected positions for those weapons. It was understood that these operations promised great attrition on both sides. But it was commonly excepted that the Allies could afford substantial losses, given the continuing flow of Americans into France, whereas the Germans had largely expended their reserves during earlier operations.

Note: The battle of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive (September 26 to November 11, 1918 resulted in the most U.S. military deaths in U.S. history where 26,277 soldiers were killed fighting against the German Empire. Many Historians have criticized The Corps headquarters that had issued the careless orders for the divisions to “advance at all costs”.

On September 25 orders we received that the division would attack the next morning at 5:30 AM. At 7 o’clock that night the regiment started to march into position in the front line trenches. At midnight the Allied Artillery bombardment began and as each whistling shell was on its way to the German defenses it was given a silent cheer by the men of the regiment as they waited in the trenches.

"Over the Top"

At 5:30 AM on the morning of September 26, 1918 the 363 infantry with the 181st infantry brigade on there right and the 138th infantry on their left, went “over the top” down from the shell towards slope‘s of Mt. des Allieux into no man’s land. There was a heavy fog that hung over the landscape. The rolls of barbed wire in front of the French trenches was thick, high and uncut. Ten minutes after going over the top the advancing companies found it impossible to keep contact with each other in the fog. Even Platoon leaders were unable to keep their commands together for by this time to smoke barrage that had been laid down had added to the obscurity and one was able to see but only a few yards ahead.

Scattered but undaunted bands up infantrymen rush ford that’s across no man’s land forwarded to create that rent close to the front of the German trenches leapt over the German Barbwire and jumped into his trenches were a few of the remaining Germans had survived the American barrage and who were waiting for the Yanks.

These Germans were quickly disposed of and the Americans with orders to proceed with all haste went on into Bois De Cheppy - like packs of hounds after rabbits.

As the first waves of the regiment cleared the north edge of the woods the fog lifted in the first real resistance was met - enemy machine nests and gunners, snipers and artillery firing at point blank range. Here officers and men of the regiment began to fall and here in the space up just a few minutes, it was learned that their threatening flanking moments against the Germans strong points with a continued and determined advance we’re bringing the Germans out of battle their positions to surrender with hands raised and cries of “Kamerad”.

Prisoners began to pour back into the American lines. One company captured three field pieces 2 of which were still firing. The 363rd had advance into the artillery positions and the Germans were in an disorganize route. The regimen advance continued. The town of Very was captured and the scattered companies of the first and second battalions we’re moving again strengthening resistance on the slopes north and east of Very when night fell and the order came to withdraw and hold the slopes north and east of town.

The men had found their first day of battle to be one of sport they went after snipers concealed in bushes and trees as one would go on a quail hunt. But the second and succeeding days with the enemy throwing his full weight and all available strength against the attack which threaten Sedan and most important lines of communication on the Western front the battle settled into a yard by yard gain - hanging on under shell and machine gun fire.

The roads in the rear where shell torn and jammed with traffic, food and supplies were slow in getting up to the lines. The men were hungry, water which scarce, the nights were rainy, there was no shelter. At times the regiment had to throw in all of its units to fill gaps that appeared in the line but held a wide front. But the Germans were stopped at every counterattack, not an inch of ground was lost to them.

The regiment had made good and it’s very first battle it had not only done all that was expected but had extended it’s flanks and had thrown in troops were other units have been held back and needed assistance. The officers and the men were exhausted after nine days of fighting when they were relieved October 5, 1918

The fighting was extreme with charges and counter charges, point blank fire. Grenades and bayonets. It rained day and night. After some ten days of extreme fighting we were sent back a few miles to a rest billet and rolling kitchen. Before we had been deluged, the order came down that we had to get back. The general offensive was starting! The Argonne Forest where our 362nd was almost wiped out from Buck to Brass”

So as not to give away our strength and positions all troops and equipment were moved out at night by trucks and horse and wagons sloshing through the rain and deep mud and always under a barrage of constant shelling. Fear of being seen and destroyed, our rolling field kitchens would hide in the Woods all day and serve us only at night under darkness. Many on kitchen duty were nonetheless killed or wounded keeping hot coffee ready for our battle weary troops. Heavy traffic on those muddy, crowded clogged roads kept our ambulances bogged down.

Our wounded had to shelter for days in dugouts or the bombed-out cellars of Very. Our wounded who could walk, staggered back through the lines towards the field hospitals. Our critically wounded. Outdoor only just sit propped up against trees and wait . We became used to the constant ear-splitting barrage of overhead artillery and exploding shells; we never became used to the terror filled screams of the wounded horses, never.

The attack on St-Mihiel, 12 September proved quite successful, The American Army quickly occupied the salient, capturing 450 guns and 16,000 prisoners at the cost of 7,000 casualties. The “next show” turned out to be the Meuse-Argonne, the battle that ultimately helped change the course of the war and contributed to the surrender of the German forces. By far, the Meuse-Argonne was the single most deadly battle for United States forces.

This forty-seven day slaughter claimed the lives of 26,277 Americans and wounded an additional 95,786 out of the 1.2 million who fought. Here the 91st Division fought on the front lines of the Meuse- Argonne. In the first days of this battle, the 91st Division, although inexperienced, gained more ground than any other American division units flanks. However, it paid a heavy price in terms of American lives.

Each of the German positions was skillfully organized in depth covered with elaborate belts of barbed wire and supported by concrete machine-gun and artillery emplacements which provided alternative protected positions for those weapons. All that could be done to improve observation posts. signal communications. routes, trails and light railway to assist the defense received meticulous attention by German engineer troops before and throughout the operations. In addition to the fully developed positions above mentioned were other partly organized defense lines which were intensively improved as need for their use increased. With Turkey. Bulgaria. and Austria on the verge of collapse. Germany's only remaining hope was to stave off defeat by dogged fighting on French soil until the Allies would grant favorable peace terms.

Each of the German positions was skillfully organized in depth covered with elaborate belts of barbed wire and supported by concrete machine-gun and artillery emplacements which provided alternative protected positions for those weapons. It was understood that these operations promised great attrition on both sides. But it was commonly excepted that the Allies could afford substantial losses, given the continuing flow of Americans into France, whereas the Germans had largely expended their reserves during earlier operations.

Note: The battle of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive (September 26 to November 11, 1918 resulted in the most U.S. military deaths in U.S. history where 26,277 soldiers were killed fighting against the German Empire. Many Historians have criticized The Corps headquarters that had issued the careless orders for the divisions to “advance at all costs”.

AT ELEVEN-THIRTY that night (23/12 o'clock) the heavy long range guns of the army artillery opened fire on selected targets in the enemy country. This bombardment grew in power and in intensity throughout the night. At 2:30 o'clock, all the guns of the corps and divisional artillery, silent up to that moment, went into action together. It is useless to try to describe that bombardment; those who lay under it during the hours before the "jump-off" will never forget it. It was so vast, so stunning, and the noise was so overwhelming that no one could grasp the whole. The German trenches were marked in the darkness by a line of leaping fire, punctuated now and then by the higher bursts of some particularly heavy shell. The retaliatory fire by German batteries passed over the heads of our leading regiments. Although the 363rd Infantry found no trenches sufficient for protection, and as, the night was warm them men preferred lying on the ground on the hill, no casualty occurred during the bombardment, as projectiles from the our own artillery passed well over the heads of the men.

Although the Wild West Division had shown more grit than its allied divisions on the east and west and their inability to keep pace exposed the flanks of the 91st division to enfilading enemy fire. Despite the 91st making impressive gains on the battlefield while the other divisions could not, clearly showed that the tremendous cost of their gains did not surpass the benefits.

“At a time when the divisions on its flanks were faltering and even falling back, the Ninety-first pushed ahead and steadfastly clung to every yard gained.” — George Cameron, Commander V Corps, Relief orders to the 91st Division

When the leading waves of the 363rd Infantry passed over La Cigalerie Butte, they entered the valley of the Buanthe into a cloud and mist which completely concealed them on Vauquois Hill less than a half-mile to the west. Similarly, the 181st Brigade, advancing with the 362nd on the right and the 361st on the left, was able to cross No-man's-land (the valley of the Buanthe) through this cloud of smoke and mist without suffering casualties. All of the 363rd waves and the liaison group between the 35th and 91st Divisions crossed No-man's-land thus concealed, the last elements leaving La Cigalerie Butte at 6 o’clock.

At the specified rate of 100 yards in every five minutes, the three leading regiments passed through the prepared lanes in the old French wire, deployed in No-man's-land and went forward without opposition. There was no delay in their movement.

Although the Wild West Division had shown more grit than its allied divisions on the east and west and their inability to keep pace exposed the flanks of the 91st division to enfilading enemy fire. Despite the 91st making impressive gains on the battlefield while the other divisions could not, clearly showed that the tremendous cost of their gains did not surpass the benefits.

“At a time when the divisions on its flanks were faltering and even falling back, the Ninety-first pushed ahead and steadfastly clung to every yard gained.” — George Cameron, Commander V Corps, Relief orders to the 91st Division

When the leading waves of the 363rd Infantry passed over La Cigalerie Butte, they entered the valley of the Buanthe into a cloud and mist which completely concealed them on Vauquois Hill less than a half-mile to the west. Similarly, the 181st Brigade, advancing with the 362nd on the right and the 361st on the left, was able to cross No-man's-land (the valley of the Buanthe) through this cloud of smoke and mist without suffering casualties. All of the 363rd waves and the liaison group between the 35th and 91st Divisions crossed No-man's-land thus concealed, the last elements leaving La Cigalerie Butte at 6 o’clock.

At the specified rate of 100 yards in every five minutes, the three leading regiments passed through the prepared lanes in the old French wire, deployed in No-man's-land and went forward without opposition. There was no delay in their movement.

"We wasn't nowhere ... but slugging through some black dream that didn'thave no end"

The two infantry battalions, with machine gun companies attached, were stationed between the two infantry brigades, ready to support either. Many prisoners and machine guns were captured by the two brigades in passing through Bois de Cheppy.

German chemists had perfected a method of releasing chlorine gas from pressurized cylinders and thousands of troops were smothered in a ghostly green cloud of chlorine. The commander of British Expeditionary Force, Sir John French, called the use of gas "a cynical and barbarous disregard of the well-known usages of civilised war".

Letters home described the ruined countryside and villages around, as well as the sights—and stench—of constant battle. “Besides the desolation visible to the eye there was the desolation visible to the nose. You could often see old bones, boots, clothing and things besides lots of recent ones.”

The most widely used, mustard gas, could kill by blistering the lungs and throat if inhaled in large quantities. Its effect on masked soldiers, however, was to produce terrible blisters all over the body as it soaked into their woollen uniforms. Contaminated uniforms had to be stripped off as fast as possible and washed - not exactly easy for men under attack on the front line.

"I fear it will produce a tremendous scandal in the world... war has nothing to do with chivalry any more. The higher civilisation rises, the viler man becomes," wrote Gen Karl von Einem, commander of the German Third Army in France.

Soldiers describe a chlorine attacks, referring to the gas's characteristic green color - victims of a chlorine attack would choke. The gas reacts quickly with water in the airways to form hydrochloric acid, swelling and blocking lung tissue, and causing suffocation. The 91st Regiment suffered 3 different gas attacks during their offensive.

But by this time, chlorine was no longer being used alone. Another, more dangerous "irritant", phosgene, was the main killer. But phosgene was slow to act - victims may not develop any symptoms for hours or even days - so it may not quite fit with the narrative of gas attacks at that moment in time.

German chemists had perfected a method of releasing chlorine gas from pressurized cylinders and thousands of troops were smothered in a ghostly green cloud of chlorine. The commander of British Expeditionary Force, Sir John French, called the use of gas "a cynical and barbarous disregard of the well-known usages of civilised war".

Letters home described the ruined countryside and villages around, as well as the sights—and stench—of constant battle. “Besides the desolation visible to the eye there was the desolation visible to the nose. You could often see old bones, boots, clothing and things besides lots of recent ones.”

The most widely used, mustard gas, could kill by blistering the lungs and throat if inhaled in large quantities. Its effect on masked soldiers, however, was to produce terrible blisters all over the body as it soaked into their woollen uniforms. Contaminated uniforms had to be stripped off as fast as possible and washed - not exactly easy for men under attack on the front line.

"I fear it will produce a tremendous scandal in the world... war has nothing to do with chivalry any more. The higher civilisation rises, the viler man becomes," wrote Gen Karl von Einem, commander of the German Third Army in France.

Soldiers describe a chlorine attacks, referring to the gas's characteristic green color - victims of a chlorine attack would choke. The gas reacts quickly with water in the airways to form hydrochloric acid, swelling and blocking lung tissue, and causing suffocation. The 91st Regiment suffered 3 different gas attacks during their offensive.

But by this time, chlorine was no longer being used alone. Another, more dangerous "irritant", phosgene, was the main killer. But phosgene was slow to act - victims may not develop any symptoms for hours or even days - so it may not quite fit with the narrative of gas attacks at that moment in time.

Meuse-Argonne Offensive, - September 26 to November 11, 1918,

Scenes of 78th and 91st Divisions

Proudly powered by Weebly