1815 Reenactors

The Battle Of New Orleans

In 1814, the British burn the White House and the US Capitol building in Washington. On October 14, 1814, Kentucky Governor Isaac Shelby issued a call for men to join Gen. Andrew Jackson’s command for the New Orleans campaign, The total strength of the Kentucky militia raised for the New Orleans campaign was 2,256. To these must be added the officers and men of the Seventh Regiment of United States Infantry (who were recruited in Kentucky), at that time 465-strong, bringing the grand total of Kentucky troops up to 2,721. Of Andrew Jackson’s force of 4,600, almost one-fourth were Kentuckians.

The Kentucky Riflemen

Years following the epic battle, an article appeared in an 1832, edition of a Boston Newspaper, The Republic. The story, by an unidentified British Officer, told of a lone Kentucky marksman at the Battle of New Orleans:

“We marched,” said this officer, “in solid column in a direct line, upon the American defenses. I belonging to the staff; and as we advanced, we watched through our glasses, the position of the enemy, with that intensity an officer only feels when marching into the jaws of death. It was a strange sight, that breastwork, with the crowds of beings behind, their heads only visible above the line of defense. We could distinctly see the long rifles lying on the works, and the batteries in our front with their great mouths gaping towards us. We could see the position of General Jackson, with his staff around him. But what attracted our attention most was the figure of a tall man standing on the breastworks dressed in linsey-woolsey, with buckskin leggins and a broad-brimmed hat that fell around his face almost concealing his features. He was standing in one of those picturesque graceful attitudes peculiar to those natural men dwelling in forests. The body rested on the left leg and swayed with a curved line upward. The right arm was extended, the hand grasping the rifle near the muzzle, the butt of which rested near the toe of his right foot. With his left hand he raised the rim of his hat from his eyes and seemed gazing intently on our advancing column. The cannon of the enemy had opened up on us and tore through our ranks with dreadful slaughter; but we continued to advance unwavering and cool, as if nothing threatened our program.

‘The roar of the cannon had no effect upon the figure before us; he seemed fixed and motionless as a statute. At last he moved, threw back his hat rim over the crown with his left hand, raised his rifle and took aim at our group. At whom had he leveled his piece? But the distance was so great that we looked at each other and smiled. We saw the rifle flash and very rightly conjectured that his aim was in the direction of our party. My right hand companion, as noble a fellow as ever rode at the head of a regiment, fell from his saddle. The hunter paused a few moments without moving the gun from his shoulder. Then he reloaded and resumed his former attitude. Throwing the hat rim over his eyes and again holding it up with the left hand, he fixed his piercing gaze upon us, as if hunting out another victim. Once more, the hat rim was thrown back, and the gun raised to his shoulder. This time we did not smile, but cast our glances at each other, to see which of us must die. When again the rifle flashed another of our party dropped to the earth. There was something most awful in this marching to certain death. The cannon and thousands of musket balls played upon our ranks, we cared not for; for there was a chance of escaping them. Most of us had walked as coolly upon batteries more destructive, without quailing, but to know that every time that rifle was leveled toward us, and its bullet sprang from the barrel, one of us must surely fall; to see it rest, motionless as if poised on a rack, and know, when the hammer came down, that the messenger of death drove unerringly to its goal, to know this, and still march on, was awful.

‘I could see nothing but the tall figure standing on the breastworks; he seemed to grow, phantom-like, higher and higher, assuming through the smoke the supernatural appearance of some great spirit of death. Again did he reload and discharge and reload and discharge his rifle with the same unfailing aim, and the same unfailing result; and it was with indescribable pleasure that I beheld, as we marched [towards] the American lines, the sulphorous clouds gathering around us, and shutting that spectral hunter from our gaze.

‘We lost the battle, and to my mind, that Kentucky Rifleman contributed more to our defeat than anything else; for which he remained to our sight, our attention was drawn from our duties. And when at last, we became enshrouded in the smoke, the work was completed, we were in utter confusion and unable, in the extremity, to restore order sufficient to make any successful attack. The battle was lost.”

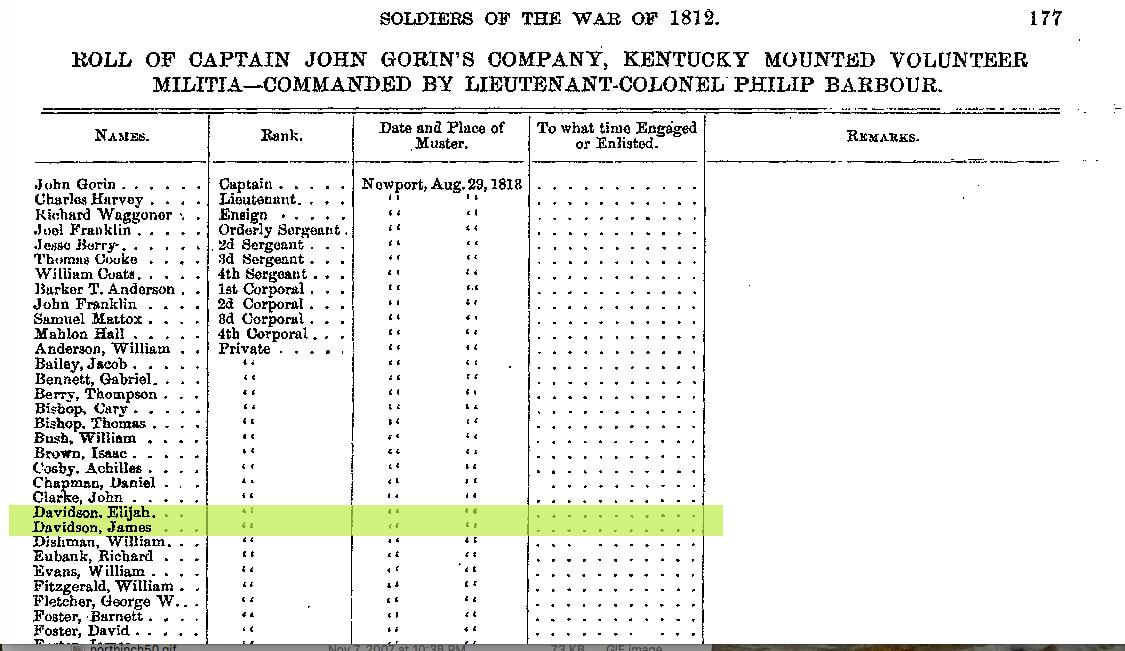

At 32 yrs. old, Elijah Davidson, his brother James and his brother in law, Peter Butler join Captain Gorin’s Company, with the Kentucky Mounted Volunteer Militia’s 10th Regiment, Commanded by Col. Philip Barbour and foughtt at the Battle of New Orleans on the morning of January 8, 1815. The British suffered an estimated 300 killed and 1,200 wounded while the Americans counted only 13 killed and 52 wounded or missing.

In 1814, the British burn the White House and the US Capitol building in Washington. On October 14, 1814, Kentucky Governor Isaac Shelby issued a call for men to join Gen. Andrew Jackson’s command for the New Orleans campaign, The total strength of the Kentucky militia raised for the New Orleans campaign was 2,256. To these must be added the officers and men of the Seventh Regiment of United States Infantry (who were recruited in Kentucky), at that time 465-strong, bringing the grand total of Kentucky troops up to 2,721. Of Andrew Jackson’s force of 4,600, almost one-fourth were Kentuckians.

The Kentucky Riflemen

Years following the epic battle, an article appeared in an 1832, edition of a Boston Newspaper, The Republic. The story, by an unidentified British Officer, told of a lone Kentucky marksman at the Battle of New Orleans:

“We marched,” said this officer, “in solid column in a direct line, upon the American defenses. I belonging to the staff; and as we advanced, we watched through our glasses, the position of the enemy, with that intensity an officer only feels when marching into the jaws of death. It was a strange sight, that breastwork, with the crowds of beings behind, their heads only visible above the line of defense. We could distinctly see the long rifles lying on the works, and the batteries in our front with their great mouths gaping towards us. We could see the position of General Jackson, with his staff around him. But what attracted our attention most was the figure of a tall man standing on the breastworks dressed in linsey-woolsey, with buckskin leggins and a broad-brimmed hat that fell around his face almost concealing his features. He was standing in one of those picturesque graceful attitudes peculiar to those natural men dwelling in forests. The body rested on the left leg and swayed with a curved line upward. The right arm was extended, the hand grasping the rifle near the muzzle, the butt of which rested near the toe of his right foot. With his left hand he raised the rim of his hat from his eyes and seemed gazing intently on our advancing column. The cannon of the enemy had opened up on us and tore through our ranks with dreadful slaughter; but we continued to advance unwavering and cool, as if nothing threatened our program.

‘The roar of the cannon had no effect upon the figure before us; he seemed fixed and motionless as a statute. At last he moved, threw back his hat rim over the crown with his left hand, raised his rifle and took aim at our group. At whom had he leveled his piece? But the distance was so great that we looked at each other and smiled. We saw the rifle flash and very rightly conjectured that his aim was in the direction of our party. My right hand companion, as noble a fellow as ever rode at the head of a regiment, fell from his saddle. The hunter paused a few moments without moving the gun from his shoulder. Then he reloaded and resumed his former attitude. Throwing the hat rim over his eyes and again holding it up with the left hand, he fixed his piercing gaze upon us, as if hunting out another victim. Once more, the hat rim was thrown back, and the gun raised to his shoulder. This time we did not smile, but cast our glances at each other, to see which of us must die. When again the rifle flashed another of our party dropped to the earth. There was something most awful in this marching to certain death. The cannon and thousands of musket balls played upon our ranks, we cared not for; for there was a chance of escaping them. Most of us had walked as coolly upon batteries more destructive, without quailing, but to know that every time that rifle was leveled toward us, and its bullet sprang from the barrel, one of us must surely fall; to see it rest, motionless as if poised on a rack, and know, when the hammer came down, that the messenger of death drove unerringly to its goal, to know this, and still march on, was awful.

‘I could see nothing but the tall figure standing on the breastworks; he seemed to grow, phantom-like, higher and higher, assuming through the smoke the supernatural appearance of some great spirit of death. Again did he reload and discharge and reload and discharge his rifle with the same unfailing aim, and the same unfailing result; and it was with indescribable pleasure that I beheld, as we marched [towards] the American lines, the sulphorous clouds gathering around us, and shutting that spectral hunter from our gaze.

‘We lost the battle, and to my mind, that Kentucky Rifleman contributed more to our defeat than anything else; for which he remained to our sight, our attention was drawn from our duties. And when at last, we became enshrouded in the smoke, the work was completed, we were in utter confusion and unable, in the extremity, to restore order sufficient to make any successful attack. The battle was lost.”

At 32 yrs. old, Elijah Davidson, his brother James and his brother in law, Peter Butler join Captain Gorin’s Company, with the Kentucky Mounted Volunteer Militia’s 10th Regiment, Commanded by Col. Philip Barbour and foughtt at the Battle of New Orleans on the morning of January 8, 1815. The British suffered an estimated 300 killed and 1,200 wounded while the Americans counted only 13 killed and 52 wounded or missing.

Kentucky Long Rifles and Powder Horns

"They're comin' on their all fours!"

An unknown eyewitness, fighting from the top of the breastworks defending New Orleans, describes the battle.

"The Colonel from Bardstown, was the first one who gave us orders to fire from our part of the line; and then, I reckon, there was a pretty considerable noise... Directly after the firing began, Capt. Patterson, I think he was from Knox County, Kentucky, but an Irishman born, came running along. He jumped upon the brestwork (sic) and stooping a moment to look through the darkness as well as he could, he shouted with a broad North of Ireland brogue, 'shoot low, boys! shoot low! rake them - rake them! They're comin' on their all fours!'

“It was so dark that little could be seen, until just about the time the battle ceased. The morning had dawned to be sure, but the smoke was so thick that every thing seemed to be covered up in it. Our men did not seem to apprehend any danger, but would load and fire as fast as they could, talking, swearing, and joking all the time. All ranks and sections were soon broken up. After the first shot, everyone loaded and banged away on his own hook.

Henry Spillman did not load and fire quite so often as some of the rest, but every time he did fire he would go up to the brestwork, look over until he could see something to shoot at, and then take deliberate aim and crack away.

At one time I noticed, a little on our right, a curious kind of a chap named Ambrose Odd, one of Captain Higdon's company, and known among the men by the nickname of 'Sukey,' standing coolly on the top of the brestworks and peering into the darkness for something to shoot at. The balls were whistling around him and over our heads, as thick as hail, and Col. Slaughter coming along, ordered him to come down.

The Colonel told him there was policy in war, and that he was exposing himself too much. Sukey turned around, holding up the flap of his old broad brimmed hat with one hand, to see who was speaking to him, and replied: 'Oh! never mind Colonel - here's Sukey - I don't want to waste my powder, and I'd like to know how I can shoot until I see something?' Pretty soon after, Sukey got his eye on a red coat, and, no doubt, made a hole through it, for he took deliberate aim, fired and then coolly came down to load again

When the smoke had cleared away and we could obtain a fair view of the field, it looked, at the first glance, like a sea of blood. It was not blood itself which gave it this appearance but the red coats in which the British soldiers were dressed. Straight out before our position, for about the width of space which we supposed had been occupied by the British column, the field was entirely covered with prostrate bodies. In some places they were laying in piles of several, one on the top of the other."

An unknown eyewitness, fighting from the top of the breastworks defending New Orleans, describes the battle.

"The Colonel from Bardstown, was the first one who gave us orders to fire from our part of the line; and then, I reckon, there was a pretty considerable noise... Directly after the firing began, Capt. Patterson, I think he was from Knox County, Kentucky, but an Irishman born, came running along. He jumped upon the brestwork (sic) and stooping a moment to look through the darkness as well as he could, he shouted with a broad North of Ireland brogue, 'shoot low, boys! shoot low! rake them - rake them! They're comin' on their all fours!'

“It was so dark that little could be seen, until just about the time the battle ceased. The morning had dawned to be sure, but the smoke was so thick that every thing seemed to be covered up in it. Our men did not seem to apprehend any danger, but would load and fire as fast as they could, talking, swearing, and joking all the time. All ranks and sections were soon broken up. After the first shot, everyone loaded and banged away on his own hook.

Henry Spillman did not load and fire quite so often as some of the rest, but every time he did fire he would go up to the brestwork, look over until he could see something to shoot at, and then take deliberate aim and crack away.

At one time I noticed, a little on our right, a curious kind of a chap named Ambrose Odd, one of Captain Higdon's company, and known among the men by the nickname of 'Sukey,' standing coolly on the top of the brestworks and peering into the darkness for something to shoot at. The balls were whistling around him and over our heads, as thick as hail, and Col. Slaughter coming along, ordered him to come down.

The Colonel told him there was policy in war, and that he was exposing himself too much. Sukey turned around, holding up the flap of his old broad brimmed hat with one hand, to see who was speaking to him, and replied: 'Oh! never mind Colonel - here's Sukey - I don't want to waste my powder, and I'd like to know how I can shoot until I see something?' Pretty soon after, Sukey got his eye on a red coat, and, no doubt, made a hole through it, for he took deliberate aim, fired and then coolly came down to load again

When the smoke had cleared away and we could obtain a fair view of the field, it looked, at the first glance, like a sea of blood. It was not blood itself which gave it this appearance but the red coats in which the British soldiers were dressed. Straight out before our position, for about the width of space which we supposed had been occupied by the British column, the field was entirely covered with prostrate bodies. In some places they were laying in piles of several, one on the top of the other."

THE LEGEND OF THE KENTUCKY RIFLEMAN at the battle of New Orleans Jan 8, 1815, is told of how the British columns advancing on Jackson’s lines are suddenly halted by a single volley of rifle fire, thrown into confusion and subsequently “melted down” by twenty minutes of deadly firing, an unrelenting fire from Kentuckians and Tennesseans.

The supremacy of Kentucky and Tennessee long-rifles in deciding the battle was undisputed, but a major contribution was the American gunners whose cannonade with all their advantages of heavier guns, well positioned with firm supports, a well fortified line and unlimited ammunition riddled the advancing columns with wide-swaths of death.

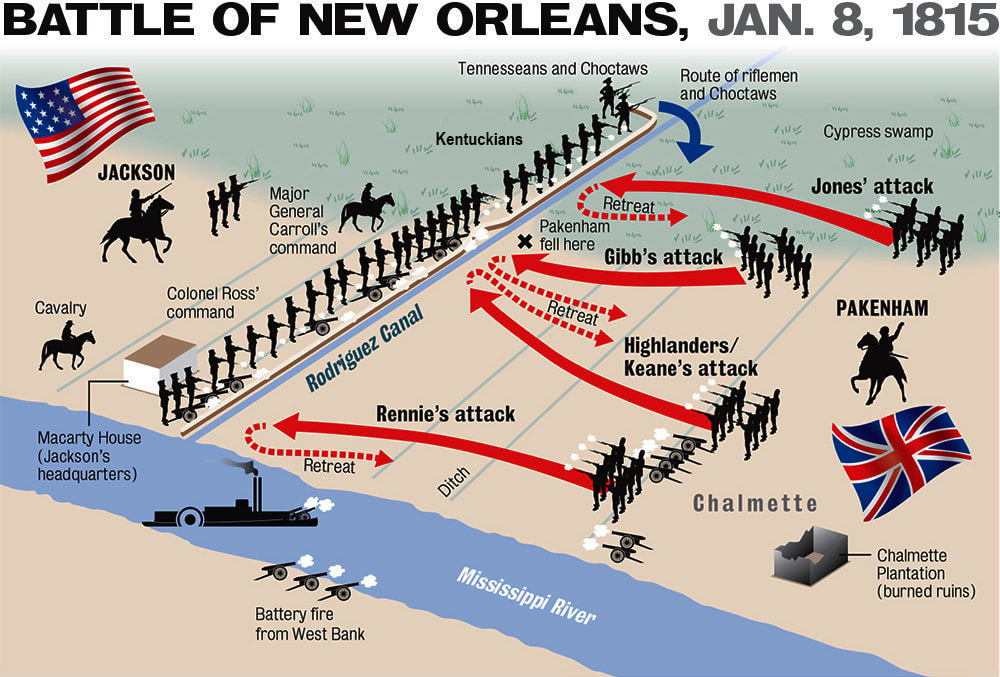

The British plan of attack involved a two-pronged assault. Because the ground was so marshy the men were forced to advance in columns rather than abreast. However the British 3rd Brigade became disordered before reaching the American line. They halted with the first volley of gunfire, instead of advancing they commented to returning fire, but panic had already set in. The stalled columns gave the Americans opportunity to inflict heavy casualties, decimating ranks and killing Gen. Pakenham. These losses were so great, that the second in command refuse to renew their attack.

One British veteran’s recollection: “Every shot riddled us through, as it was we might ha’ stood some sort of chance if we’d been brought up in line, but in close columns as we was, thousands of our men were cut down in no time. I hadn’t been standing there three minutes before I could walk over the muddy canal in front of us which was about four feet deep, onto o’ dead bodies o’ the 44th Regiment. The 93rd Highlanders scrambled over us into the enemy’s works; but not a man of em’ came back”.

The supremacy of Kentucky and Tennessee long-rifles in deciding the battle was undisputed, but a major contribution was the American gunners whose cannonade with all their advantages of heavier guns, well positioned with firm supports, a well fortified line and unlimited ammunition riddled the advancing columns with wide-swaths of death.

The British plan of attack involved a two-pronged assault. Because the ground was so marshy the men were forced to advance in columns rather than abreast. However the British 3rd Brigade became disordered before reaching the American line. They halted with the first volley of gunfire, instead of advancing they commented to returning fire, but panic had already set in. The stalled columns gave the Americans opportunity to inflict heavy casualties, decimating ranks and killing Gen. Pakenham. These losses were so great, that the second in command refuse to renew their attack.

One British veteran’s recollection: “Every shot riddled us through, as it was we might ha’ stood some sort of chance if we’d been brought up in line, but in close columns as we was, thousands of our men were cut down in no time. I hadn’t been standing there three minutes before I could walk over the muddy canal in front of us which was about four feet deep, onto o’ dead bodies o’ the 44th Regiment. The 93rd Highlanders scrambled over us into the enemy’s works; but not a man of em’ came back”.

Aftermath

In an ironic twist of history, peace between America and Britain had been achieved two weeks earlier with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent. However, news of the event had not reached the shores of America. Despite its lack of impact on the outcome of the war, the battle was an important milestone in America's development. The victory gave the American people pride in their new nation and confidence in its future.

News of the treaty of Ghent, arrived in New York on February 11, a week after the city learned of Jackson's triumph. Adding to the spirit of celebration, the news that the war had ended quickly spread throughout the country. Receiving a copy of the treaty, the US Senate ratified it by a 35-0 vote on February 16 to officially bring the war to a close.

The war was viewed in the United States as a victory. This belief was propelled by the fact that the nation had successfully resisted the power of the British Empire. Success in this "second war of independence" helped forge a new national consciousness in American politics. Having gone to war for its national rights, the United States never again was refused proper treatment as an independent nation.

Carter Tarrant, Elijah’s mentor and friend dies in New Orleans serving as the regiment’s Chaplin. There is speculation he was killed because of his unrelenting position on abolition.

The name Carter Tarrant will be passed onto the next 3 generations of Davidson sons.

News of the treaty of Ghent, arrived in New York on February 11, a week after the city learned of Jackson's triumph. Adding to the spirit of celebration, the news that the war had ended quickly spread throughout the country. Receiving a copy of the treaty, the US Senate ratified it by a 35-0 vote on February 16 to officially bring the war to a close.

The war was viewed in the United States as a victory. This belief was propelled by the fact that the nation had successfully resisted the power of the British Empire. Success in this "second war of independence" helped forge a new national consciousness in American politics. Having gone to war for its national rights, the United States never again was refused proper treatment as an independent nation.

Carter Tarrant, Elijah’s mentor and friend dies in New Orleans serving as the regiment’s Chaplin. There is speculation he was killed because of his unrelenting position on abolition.

The name Carter Tarrant will be passed onto the next 3 generations of Davidson sons.

Proudly powered by Weebly